The Passenger v. Mouth to Mouth

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 9 • OPENING ROUND

The Passenger

v. Mouth to Mouth

Judged by A. Cerisse Cohen

A. Cerisse Cohen (she/her) is a writer and editor living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal Magazine, the Nation, Artsy, and other publications. She mostly covers art and books. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “I used to do some freelance work with Tess Gunty, and she was very close with two of my roommates.” / alinaccohen.wixsite.com

I am a 31-year-old woman whose life has recently been consumed by dating men, and this dual review/decision is heavily informed by that context. I can’t help it, that’s what’s on my mind these days, and the best I can do is be honest about my situation at the outset.

While reading and thinking about Antoine Wilson’s Mouth to Mouth and Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger, here’s what I valued: how I felt while I was reading, whether or not these writers kept the promises they made at the beginnings of their novels, and if their books evidenced irritating views about women.

I read The Passenger first because it’s longer, I’m a slow reader, and I was worried about finishing both books on time. And wow, does this book present well. The novel opens with a brief, chilly passage in which a hunter finds a dead girl in a snowy forest. The subsequent first section features an enigmatic dialogue between Alicia (the dead girl of the opening) and “the Kid,” a hallucinatory figure who will visit her throughout the book.

Your opinion of this book might come down to whether lines like that galvanize you or make you roll your eyes.

The pair’s conversations are interspersed with scenes of the novel’s real hero, salvage diver Bobby Western. When we meet him, he’s exploring a sunken charter plane that has crashed off New Orleans. Both a passenger and the Jepp case (which stores navigational data) are missing from the wreckage. After making this discovery, Bobby’s diving partner dies under mysterious circumstances, and Bobby begins to believe that someone is following him. He tries to escape his pursuers and finds that he can’t outrun them—or his family’s tangled past. I thought this was a fantastic, suspenseful setup, and I readied myself for an intricate plot that would offer more intrigue and some answers regarding the plane, Alicia’s death, and the malign forces at play.

But The Passenger is not especially interested in plot. Instead, we watch Western converse with friends in New Orleans eateries, move around and then out of the country, and consider his family’s history at large. His father helped develop the atomic bomb, and The Passenger devotes much space to the rivalries between physicists around the time of this invention. Toward the end of the novel, one character offers a theory of the Kennedy assassination.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

The Passenger throws multiple philosophical and narrative inquiries of epic proportion at the reader—and never fully commits to any of them. The novel reads like an underdeveloped, multi-generational family saga with a half-baked conspiracy plot, much of it told via extensive blocks of untagged dialogue that can leave the reader lost in a hazy cloud of erudite (and when the Kid talks, nonsensical) language. This may not bother some readers, especially McCarthy fans—another huge admission here: This is my first novel of his—and those who come to literature for a particular mood. Haunting images abound, and ideas swirl around death, ruins, physics, writing, and the passage of time. There’s so much to think about here! But The Passenger’s lack of cohesion and fidelity to anything, really, ultimately limits its ability to communicate.

Then there’s the issue of Alicia, who I’d describe as a schizophrenic pixie dream girl. She’s brilliant, beautiful, charismatic, and fated to die, cooped up in a psychiatric institution for much of the novel. Her brother Bobby, on the other hand, wanders through the world, dangerous job to dangerous job, basking in his lone wolf status, never really connecting with his interlocutors. In regular discourse, McCarthy’s men make proclamations such as: “If you carry your past into battle you are riding to your death. Austerity lifts the heart and focuses the vision. Travel light. A few ideas are enough. Every remedy for loneliness only postpones it.” Your opinion of this book might come down to whether lines like that galvanize you or make you roll your eyes. And I’m sorry, I’m just not interested right now.

Mouth to Mouth, like The Passenger, structures itself around conversations between men, but they’re much more entertaining. Wilson’s unnamed narrator runs into an old college acquaintance, Jeff Cook, at JFK airport, and Cook simply tells him what he’s been up to since they graduated. This mundane conceit sharply contrasts the Shakespearean dimensions of Cook’s tale, which features a near-drowning, an obsession with a Los Angeles art dealer, and an upper-crust domestic drama. A tight, linear plot structures Cook’s story, and twists and turns abound. I fear giving more away and ruining the experience for the next reader. At 179 pages, broken into 65 chapters, Mouth to Mouth is a svelte little volume with nary an excess word. No editing notes.

This reviewer, admittedly, is a skier with a penchant for propulsive stories about art, money, and power, and is not going to apologize for it.

I can imagine another reader’s potential complaints. Mouth to Mouth is an unapologetically bourgeois narrative about a rarefied world. It features a celebrity house-sitting gig, expensive paintings, and an international ski vacation. Although it is quite confident in its prose and drive, it lacks The Passenger’s scope and ambition (although I did wonder, while reading the latter, where one draws the line between ambition and hubris).

The Passenger continues to haunt me—I recently dreamed about a plane crashing into a pool, and I felt the book had meaningfully wormed its way into my subconscious. When I finished Mouth to Mouth, I simply thought: Well, that was fun. This reviewer, admittedly, is a skier with a penchant for propulsive stories about art, money, and power, and is not going to apologize for it.

Toward the end of Mouth to Mouth, the narrator describes Cook’s tale as “a story he seemed to have told off the cuff, unrehearsed, spontaneously upon finally meeting an ideal audience.” Maybe I was the ideal audience here. I experienced the book as a performance that did exactly what it set out to do—tell a surprising story with sharply drawn characters and intrigue that paid off. The timing was good, the chemistry was there, this book treated me well. That’s my choice.

Advancing:

Mouth to Mouth

Match Commentary

with Meave Gallagher and Alana Mohamed

Meave Gallagher (she/her): Here we are again, friends, some of us hanging on by our fingernails, but together nevertheless!

As Rosecrans explained yesterday, I will be doing some of the commentating this year with my dear friend and fellow librarian Alana Mohamed. Alana works for New York City’s library system and is a talented writer and erstwhile archivist—and I think the world of her. Alana, welcome to the annual gathering of the ravening hordes (bibliophagus variety)!

Alana Mohamed (she/her): Hello, ravening hordes! Meave, you have many kind things to say about me, but I feel the need to clarify that while I do have an MLS, I have not practiced actual librarianship for a few years now. I do get to talk about libraries a lot, though, which is not a bad way to earn your keep. That said, I love books, I love reading, and I love talking to you, so hopefully we can all have a good time (or as good a time that can be had in…these particular times).

Meave: Absolutely. And everybody, do take anything prescriptive we say about libraries with grains of salt. We also both live in New York City, and I’m just out of school, so please excuse lapses into provinciality.

But for example, if we were to talk about libraries today, perhaps we’d mention, as outrageous as New York’s crystal-powered mayor’s attempt to exponentially shrink our three library systems’ funding may be, the police chief/city manager in McFarland, Calif., wants to evict its only library and give the building to the police department. Or how Brooklyn Public Library’s Books Unbanned initiative, which issues digital library cards to young people whose local libraries restrict access to certain literature, is a direct response to Florida librarians’ taking “controversial” books off the shelves, lest they face felony charges.

Alana: Incarcerated people also face increasingly draconian laws about what books they can read and how, in addition to what types of communication they can receive. In Florida state prisons, over 20,000 books are banned.

Meave: Floridians, for what it’s worth, the library community is fighting for you.

But shall we embark on Judge Cohen’s journeys with Billy Western and an Art Guy to… a pretty significant upset, right? I appreciate that our judge began by establishing her parameters. However, I struggle with what it means that writers “keep the promises they made at the beginnings of their novels.” How does one determine those promises and whether they’ve been kept? What author explicitly states their intentions for a novel within the text?

Alana: I think I sympathize with Judge Cohen a bit more here. I also sympathize with her not wanting to see women treated like garbage.

Meave: Yes. Yes!

Alana: But me, I like a book that makes me cry. I like when a story can connect and demonstrate complicated ideas about the world in a way an essay never could. I care about plot as well, but I think pacing might be more important, as well as striking an emotionally resonant ending note (which may not be the thing that ties the plot up neatly).

Meave: And if you believe the author promised you a neatly tied-up plot? No, too pedantic.

Alana: You probably can’t apply it evenly to every book. How does a plot or story not meeting your expectations in some way affect how you judge a book? Or are you someone who tries not to have any expectations when reading?

Meave: Well, I expect a mystery novel to end with solved mysteries, but I want surprises along the way. Whiffing the ending can sour me on an otherwise enjoyable book. I try to expect the best of most books, but I might also be harder on ones that meet my low expectations out of spite. Opinions are a finger trap!

Alana: Ha! I am always eager to solve the mystery, but it doesn’t necessarily affect my enjoyment of the story; I like seeing how people’s minds work and how things come together. I love being right, but I am delighted when I’m wrong. But when a book is not to my tastes, I tend to question myself: What does it say about me that I didn’t like this?

Don’t most people expect plot in a story? It feels like everyone thinks of a story as something that has a beginning, a rising action, and a conclusion.

Meave: Sure, most.

Alana: So I don’t think Judge Cohen is wrong to have believed The Passenger’s mystery would be solved by the end. Especially when we consider how many of McCarthy’s books have been adapted to film.

Meave: The unraveling of a mystery does lend itself to catharsis. And ticket sales.

Alana: I see you are none too convinced. But maybe a sense of catharsis is what Judge Cohen was chasing? I think I’m picking at this topic because (Hercule Poirot voice) I found myself feeling like a promise had not been delivered in this very judgment.

Meave: (Applying curling tongs to moustache) Oh?

Alana: I was disappointed that Judge Cohen didn’t carry that thread about dating throughout. I think it’s a fun way into two books that seem largely to be about the desires of men.

Meave: Of Mouth to Mouth’s buds, which would Bobby Western respect more, as A Man? The Endless Talker or the Contemplative Listener?

Alana: Ha, right? I get the sense Bobby Western (what a name) would be less perturbed by the rambling than the self-deceit. But I suppose, dating-wise, you do have certain expectations of how a thing will turn out, so maybe that criterion worked. Though if the prose and form is truly so strange, I’m not sure the opening of The Passenger promised convention or fealty to plot.

Meave: What do you think about our judge’s description of Mouth to Mouth as having “treated [her] well”? I’d love her to have elaborated on that. I prefer a book to take me out of myself; give me tangible peril over inarticulable misery any day.

It seems like the judge felt presented with a choice between two types of traditionally masculine power—surviving untethered from society versus having wealth and influence—and she went with the ski-lodge haver over the ski instructor.

Alana: Ha! Having a good time picturing Bobby Western grappling with questions of physics and mankind between wealthy clients. I get the sense that neither blew our judge away, as if Judge Cohen was racing through speed dates and ultimately glad that her time with Mouth to Mouth passed painlessly. I’m not sure that is the strongest case to make in favor of a book.

Meave: She doesn’t seem to feel passionately about either work.

Alana: I think there is more going on beneath the surface of Mouth to Mouth than Judge Cohen reveals here. One of the book’s most entertaining elements is subverting appearances, the way we are often seduced by an image of wealth and sophistication, so it’s interesting that she plays off these markers in her final remarks.

Meave: Oh, for an end to tales of seduction by an image of wealth. Let a Rabbit fall on me, call it a performance piece.

Alana: But The Passenger does come off as toxically masculine, unwilling to commit, long-winded, and maybe self-important. I would love to see Judge Cohen’s best and worst lines from each book to see what style resonates with her. Neither especially appeals to me, but she hinted at enough weird stuff in The Passenger that I would sooner pick it up over Mouth to Mouth. I would brace myself for disappointment, though.

Meave: Credit to the judge for digging into books that she may not have otherwise chosen, anyway. We do appreciate an effort!

Next up, The Book of Goose takes on Mercury Pictures Presents, with the Honorable Christina Orlando presiding. Will the mysterious French child prodigies wallop the Hollywood outsiders-turned-insiders? The émigré(e) battle royale can only have one victor!

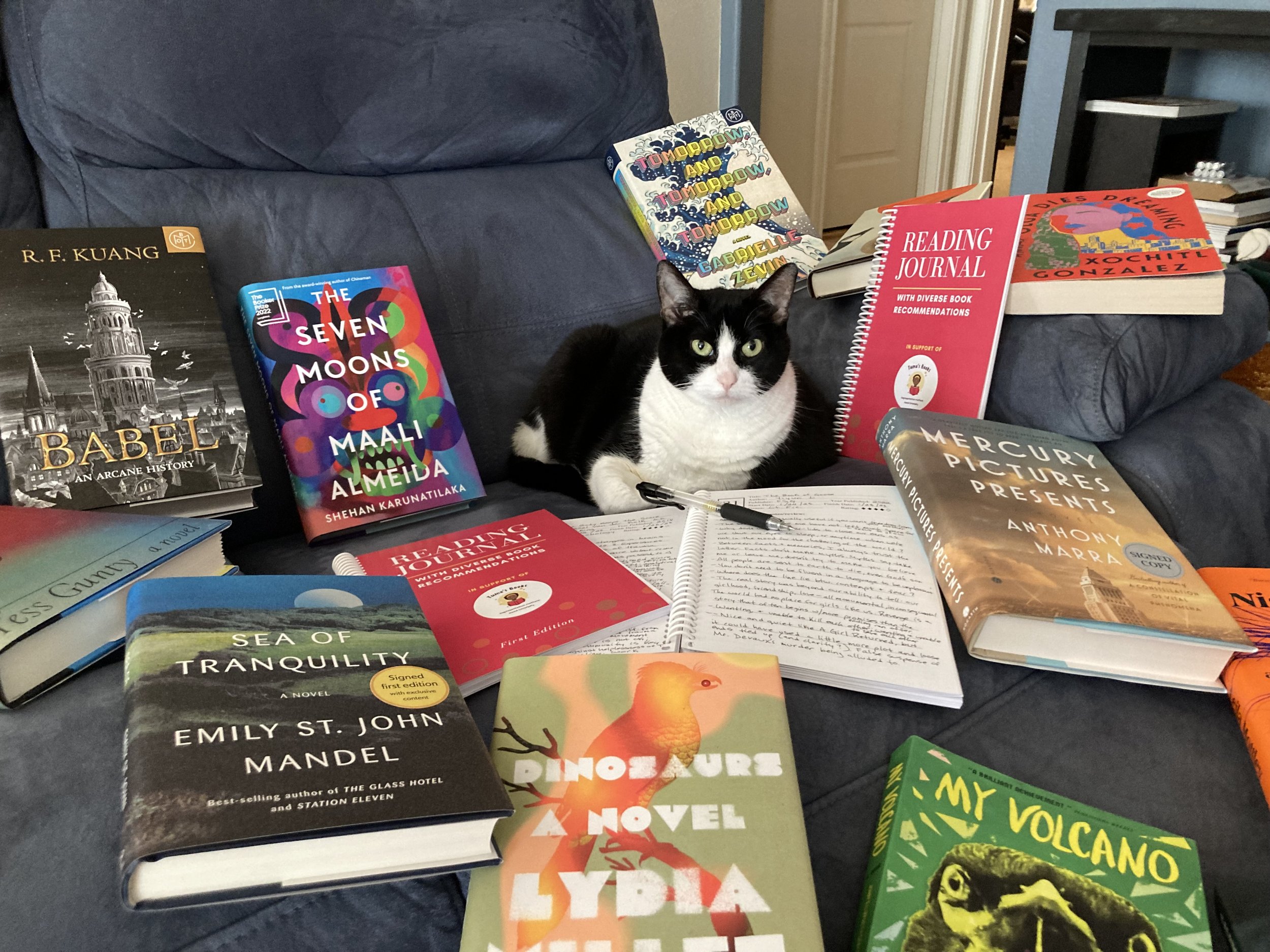

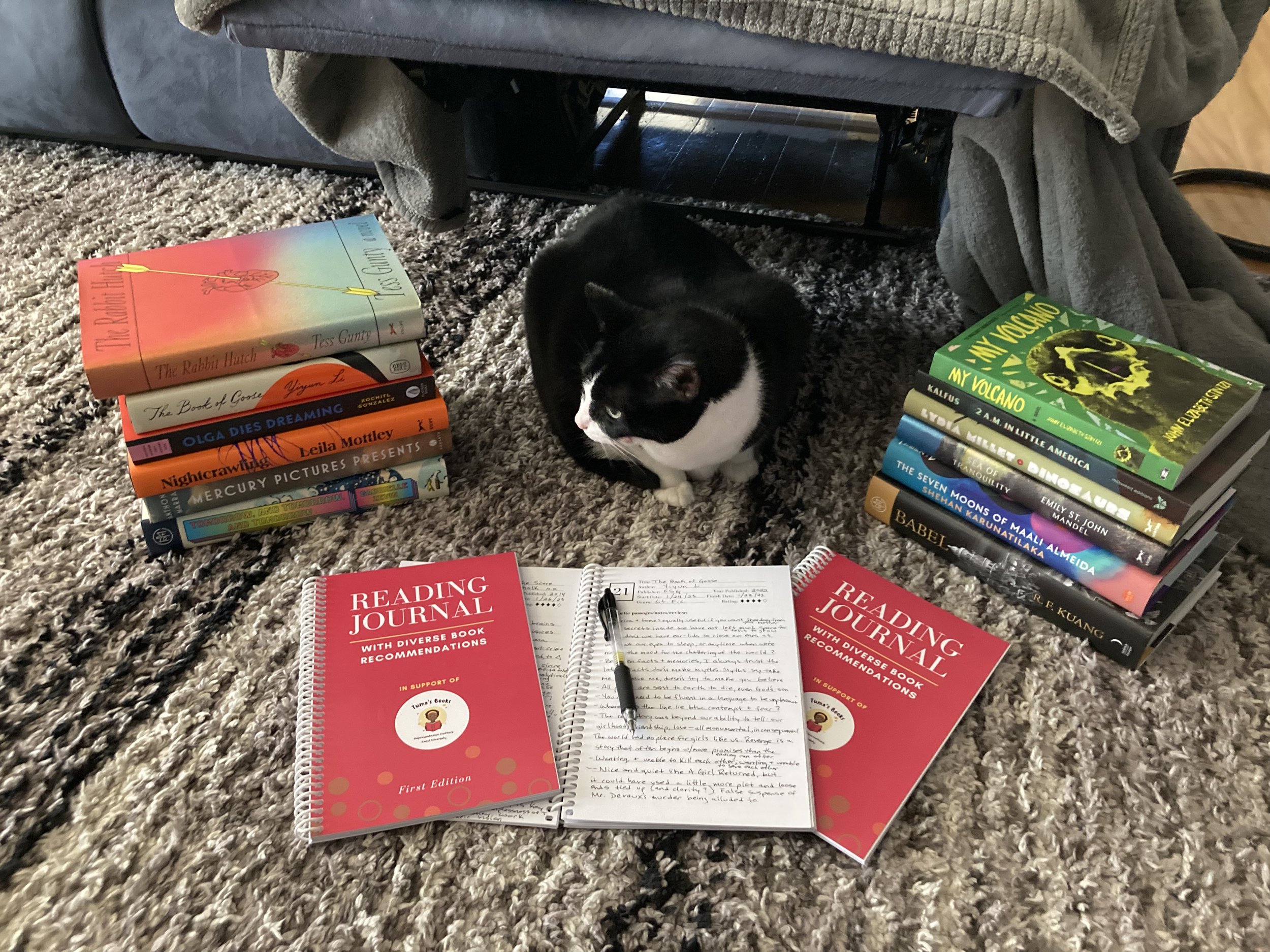

Today’s mascot

Today’s mascot, brought by Commentariat member Lauren, is Apollonia, a shorthair tuxedo cat living in Austin. Apollonia loves literary fiction, along with poetry about cats, and she read all 18 of the ToB books this year. [Wow!—ed.] She’s rooting for any of the books that included positive portrayals of cats, but already forgot which books had that, so she’s ready to just sit back and enjoy reading the judgments and comments. She loves writing down thoughts and favorite passages into the Tuma’s Books Reading Journal, and she encourages ToBers to check out her mom’s free Readers & Writers newsletter, which includes a new book giveaway each month.

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.