2 A.M. in Little America v. An Island v. My Volcano

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 8 • PLAY-IN MATCH

2 A.M. in Little America

v. An Island

v. My Volcano

Judged by Lauren Markham

Lauren Markham (she/her) is a writer based in northern California. She is the author of the award-winning book, The Far Away Brothers: Two Young Migrants and the Making of an American Life, and her stories, essays, and journalism have appeared in outlets such as the New York Times Magazine, Freeman’s, Orion, Harper’s, the Atlantic, and Guernica. Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / laurenmarkham.info

I hate competitions. I hate them so much that a few years ago, upon learning via Twitter that I would be “facing off” with writer Ingrid Rojas Contreras onstage at a lighthearted literary contest, I panicked. She, too, it turned out, was loathe for a face-off, even one in jest. So we hatched a plan. On the night of the event, she and I dressed in matching black jumpsuits and crowns of fresh flowers that we’d woven by hand the night before on her apartment floor. When she was called up on stage to read, she read my essay; I then read hers instead of mine. We so stymied the judges that they presented us a joint prize—a “Champion” medal strung on red, white, and blue ribbon that we trade back and forth every few months. (Ingrid, if you’re reading this, it’s your turn—I’ll bring you the medal the next time we hang out.) Success!

Today’s match is a particularly tough one because these three books all felt in ardent conversation with one another—as well as with the events of the world itself, and with the harrowing prospects of our collective futures.

The term “kaleidoscopic” is used annoyingly often to describe books, and yet I have to use it here.

There’s An Island by Karen Jennings, a haunting tale of the lighthouse keeper on an isolated island in an unnamed country recovering from past strife. The protagonist is stricken by his own past—a past that, like any citizen, is tangled up with the history of his country. Jennings metes out the man’s history over the course of the novel in tiny morsels—she’s set up the past like a seething mystery such that we’re hungry for them, eager to piece together who this protagonist is, why he’s relegated himself to a life alone on this island, and the circumstances that brought him there. Meanwhile, around his stilled atoll, things are changing for the worse again. The climate has shifted such that it’s difficult to fish or catch crabs anymore; renewed violence is fomenting on the mainland; and, most terrifying of all, the dead are washing up on his island’s shore. Refugees. Except one of the washed-up bodies proves to be still alive. This book reads as part thriller (“he had only one sharp knife”) and part parable (“The island. The island. The island belonged to Samuel. It was his and his alone”), probing what it means to share resources and live alongside one another in our ferocious world.

And then there’s 2 A.M. in Little America, Ken Kalfus’s disorienting heartbreaker of a novel in which the United States has been splintered by a brutal civil war. Wicked things took place in the protagonist’s homeland—the former United States of America—and in his town in particular. Now almost all US citizens have been forced on the run. The book opens with a scene I’ll never forget: The protagonist, now an exile working as an electrician, is tinkering with an outage on a rooftop where he spots a woman through a window. She’s fresh out of the shower, fully naked and staring at herself in the mirror inside what he imagines that she imagines to be the privacy of her bathroom. He looks at her with magnetism and shame and then—well, he thinks he recognizes her. Does he? Later, he’ll see her again. Or will he? And then again. But no—it’s not her after all. Or is it? There’s a bedeviling mystery at the center of this book, too: Who is this mystery woman, or is it many women, the resemblance merely a trick of this displaced man’s imagination, a function of his longing for his past intact, or for an intact home?

FROM OUR SPONSOR

And finally I read My Volcano, an ambitious, astonishing pageant of a book. The term “kaleidoscopic” is used annoyingly often to describe books, and yet I have to use it here, because this book, with its dozens of storylines—from Moctezuma’s Aztec empire to a Tokyo-based scholar, to a wasp-stung shepherd in Mongolia, to a woman working at a tech start-up in San Francisco that provides soundproof rooms where people can just scream—really reads as though one is looking into a kaleidoscope, watching the book turn these bejeweled stories over and upon one another, feeling the blazing, ever-shifting light of meaning. The central premise here is that a volcano appears in Manhattan and grows many feet each day, displacing millions of people (refugees again) while also drawing others in. No one is spared the volcano’s elemental chaos. “In the weeks after the Central Park Volcano—Fuji 2—reaches its apex, things that had for a long time gone ignored began interrupting people’s lives. Ghosts of themselves began to follow them through their days, telling them all the things they’d tried to forget…” This is also a book about contemporary estrangement and violence, about the wounds and hauntings of history, of climate collapse… it’s an indescribable book, and like with any book, but especially with this one, you’ll have to read it to understand what I mean.

I was delighted to get to read each of these books, and, frankly, to read them in conversation with one another as both imaginative portraits of the unsteady future of this planet and its people, and, too, as portraits of contemporary imagination: of how today’s writers picture in detail our looming future. (Spoiler: It’s not pretty.) Climate anxiety strongly undergirds both An Island and My Volcano; the menace of past violence (civil war, political torture, mass imprisonment, gun violence, violence at the hands of the police) saturates each of these books, as does the promise of further violence and instability to come. And of course, each of these books deals deeply with the condition of exile and refugeehood. Given the context we’re all living in, these literary preoccupations come as no surprise. But it’s still remarkable to watch as these writers particularlize collective anxiety into the firm contours of story.

While some of the prose in An Island was so moving as to make me hold my breath (“Inside something small and folded began to shift. It opened outward, growing ever larger, until his arms, his throat were wrapped in it. Until he was brittle and creaking with it. He reached up. But could only feel the rasp of fingers on stubble, and beneath it, paper skin.”), there were other places where the description of the goings-on felt pat. For instance, the narrator imagines being back among people, and “Children playing. Women stopping to chatter. Cigarette smoke and street food.” Yes, we’re in the narrator’s imagination here, but there’s a lack of presence, of particularness. I felt this in other moments in the book, too, particularly those that took place on the mainland. These bits lacked the marvelous aliveness that Jennings conjured on the island and in the island’s little cottage.

I’m enraptured by this engagement with historiography and narrative power, but what were the occurrences in question, what were the facts and the narratives being portrayed?

My Volcano was propulsive and energetic and alluring and strange, with all its disparate people and pieces, and with the strange magic that permeated the book’s many worlds. But sometimes the kaleidoscope felt overwhelming, a too-muchness afoot. It’s not that the book needed reigning in—the book is most delightful in how it just goes for it—but I did, at times, particularly in the final third, find myself wishing for a tighter weave. I love a novel that makes me work to connect disparate threads of meaning. At the same time, it sometimes felt as though the author was having narrative fun at the expense of the reader’s experience.

And in 2 A.M. in Little America, while I found the mystery totally absorbing and wonderfully disorienting, the backstory of the US conflict felt a bit generalized. “We discovered that the conflict, as painful and tragic as it had been, was really a contest between texts…Opposing narratives, we learned, could easily be constructed from the same actual occurrences and objective facts.” I’m enraptured by this engagement with historiography and narrative power, but what were the occurrences in question, what were the facts and the narratives being portrayed? While the specifics of what happened during the war and who was fighting for what are not the central point of the book, the lack of practically any specifics, and the generalized terms in which the conflict is so often discussed, left me wanting, and feeling as though the conflict itself was too cookie-cutter to make me as mournful as I should have been.

How to choose? Subjectively, imperfectly, impossibly. But I chose My Volcano. I loved that the book felt like an explosive device injected into our current era—and into history itself—and detonated. I loved the bombast of the book, the feeling that I was tearing through time and space while reading it, the mystery of how all the pieces fit together, the remarkable and unrelenting presence of each rendered moment. Even the places where I found myself lost in the story, and unmoored, were deeply alive moments on the page.

I will say that I’m better off for having read each of these books. Good on anyone who manages to write a book at all—and above all, good on those who attend to the crises of our age with such care.

Flower crowns for everyone!

Advancing:

My Volcano

Match Commentary

with the Tournament of Books staff

Rosecrans Baldwin: Welcome back, welcome back, welcome back everyone! And a very big, grateful welcome back to the good folks at our marvelous presenting sponsor Field Notes.

Andrew Womack: This is our 19th edition of the Tournament of Books, and reaching that milestone is in large part thanks to our Sustaining Members, whose support keeps us going all year long. After all, work on the Tournament happens long before March, and this year has included what many of the Rooster faithful are perhaps noticing right now: this new website! It’s been a long time coming, and we hope you find it to be an improved experience over the old site. (It’s hot off the presses, so please let us know if you spot any bugs.)

Meave Gallagher: Commentariat! Long time no speak! How I have missed your high spirits. Looking forward to riotously respectful, nuanced discourse, full of strong opinions and open minds. And a special welcome to new readers and longtime lurkers. After so many years, this place can feel clubby sometimes, but if you’re here, you’re in the club!

Rosecrans: Also, I’ll mention that we asked Meave to be one of our commentators this year, because she’s amazing, also because she’s a librarian and libraries have been muchly in the news. So, for half of the month’s matches, Meave will be part of our first librarian-commentator team alongside her friend and fellow New York City librarian, Alana Mohamed.

Meave: We will all argue and applaud and converse with love, my angels with filthy souls.

Andrew: Now let’s bring in our other pair of commentators, ToB legends and novelists John Warner and Kevin Guilfoile, to talk about today’s decision.

John Warner: Thanks guys. It’s great to be back once again!

Kevin, I’m struck by Judge Markham’s story about her aversion to competition and her solution to a competitive dilemma as an opener to our annual books competition, perhaps because I don’t really perceive what we do here as a competition, and yet of course that’s what it is!

We have contestants and winners and even a prize at the end! You and I call ourselves—semi-jokingly, semi-seriously—“color commentators.” We have an audience you could easily just call “fans” who get passionately invested in the outcomes of the matches. It looks like a competition.

At the same time, is it truly a competition? The stakes here are invented, and as proud as I am to be associated with this enterprise, to my knowledge, a Rooster Winner sticker does not have the cache of a Reese’s Book Club or Read With Jenna designation. Do we even have stickers?

Kevin Guilfoile: I want to say that one of our co-conspirators made official-looking Rooster stickers many years ago and several of us surreptitiously placed them on books in a handful of stores during the competition. (I have a memory of doing that, but am I making that up?) Someone send us a photo of a Rooster sticker if you ever saw one in the wild.

Is the Rooster an actual competition? That is such a great question. We like to discuss the unintended themes that emerge when you read the shortlisted books back-to-back and I think one of those themes this year is the concept of simulations (more on this in later commentaries). With that idea fresh in my mind, I believe you could think of the ToB as a simulation of a competition. It borrows the apparatus of a real competition, but the point of it is not winning. We root for our favorite novels and authors, but, as you say, there are no stakes (other than the perceived threat that we will bring a live rooster to your home). The “winners” sometimes advance after careful consideration, but just as often the decisions are maddeningly capricious. As longtime Rooster fans will remember, we have had judges who didn’t read the books, and one who definitely advanced a novel because they liked the cover, and those decisions were all equally binding.

The Rooster is a vehicle to talk about books. To talk about how we read. Why we read. Why we choose to read the books we do, and why we enjoy them (when we do). For authors and publishers it’s probably nice to have a book in the ToB because each novel gets talked about a lot—in the judgment, in the commentary, and in the voluminous comments—by people who care as much about fiction as anybody. So who gives a shit who wins? That’s not why we’re here.

But seriously, who do you think is going to win?

John: The overlaying of competition with art made Judge Markham uncomfortable, and so she cleverly subverted it, opting out. We don’t check with authors ahead of time if they want their books to be part of the ToB, and to my knowledge, we’ve never had an author request to be removed from the competitors once selected. While we may not be Read With Jenna, I think most authors are grateful for whatever attention their work receives, though I imagine there’s plenty of those authors who would rather avoid the particulars of what happens to their book in this forum.

Unless they win, of course. Winning cures all ills, I’ve heard.

Kevin: I can’t believe you have forgotten the great Hill William dustup of 2013, in which the author of that novel demanded to be dropped from the ToB in an acerbic Facebook post (surely the least punk of all protest media). He was mostly trolling and we entirely refused, but it probably gave both his book and the Rooster a tiny bump in the old Trending Topics that week. If nothing else his indie novel got a long mention in the Los Angeles Times. By (half) pretending to take it all so self-seriously he was just playing the simulation, although, ironically, by choosing to engage at all with us (instead of just feigning indifference like everyone else), he became perhaps the most active author participant we’ve ever had.

John: But of course books do compete in the world, not just against each other, not even primarily against each other, but against other media for attention and territory in the culture. Sometimes it seems like books are in a losing battle, but here we are, another year of the Tournament of Books and some exciting action in front of us, as always.

As for the trio of competitors themselves, my personal loyalties were split between 2 A.M. in Little America and My Volcano. I think Judge Markham’s point on the lack of specificity of what calamity befell the United States is well-taken, it is a frustration that Kalfus puts in front of the reader, but I think it is a deliberate move to make us confront the part of our American psyches that think these things must be explicable, knowable.

I think the book’s point is that once the calamity occurs, the specifics become largely unimportant, the history will go unwritten.

My Volcano for me is a “honey badger novel,” a category I coined in the 2021 Tournament to describe Raven Lelani’s Luster, a novel that doesn’t give a shit and just goes wherever the authorial impulse takes it.

I think there’s a high risk to writing a honey badger novel, but when the reader connects with it, the rewards are significant.

Kevin: At one point I stopped reading My Volcano to text my college roommate and ask him if he had heard of it, because it’s exactly the kind of book that we would have been most excited about back then, arguing about it late into the night with a CD of Prince’s Lovesexy playing in the background. The audacity of it would have fired us up. Incidentally, as a middle-aged-man I still really enjoyed the novel, I just no longer have a bunch of college English majors lying on my couch who want to shout at me about it. Still have that Lovesexy CD, though.

One thing I definitely would have wanted to talk about back then is the omniscient point of view (which will come as no surprise to you because it’s a known obsession of mine that truly omniscient POVs almost never work). My Volcano makes some particularly brazen choices about who is telling this story—at times the narration is from the POV of, like, bees, for example. But then they develop a character who really is omniscient, and the often fatally distracting question—who the hell could be telling this story?—is actually answered. I thought that was brilliant and ballsy and I was leaning into the story for the rest of the ride.

John: That was perhaps ultimately what put it over the top and into the main draw. This is where most years we put our rooting hearts on our sleeves and say which books we want to win our simulated competition. For me, that’s Mercury Pictures Presents, which absorbed and moved me; Dinosaurs, which proved Lydia Millet can work in any register she wishes; and Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance, which does some things craftwise I was so taken with that I dedicated an entire newsletter to it.

Where do your sympathies lie this year?

Kevin: I think my favorite read from this bunch might have been Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, although Dinosaurs was high on my list, as well, so I am destined for some first-round disappointment. I also really enjoyed The Rabbit Hutch, which is maybe the most interesting novel made from the bones of short stories I’ve read in a long time (I’m really looking forward to talking about that one with you). Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance is also terrific. There is a ton to discuss this year, that’s for sure.

Speaking of Tomorrows, that’s when the opening round begins, as Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger tries to sidle down the aisle past Antoine Wilson’s Mouth to Mouth.

Rosecrans: Thanks guys. One final note: As you scroll down, you’ll see that our comments section this year has a mascot position—and it’s the loyal pets of the Commentariat! Here are details on how the program works.

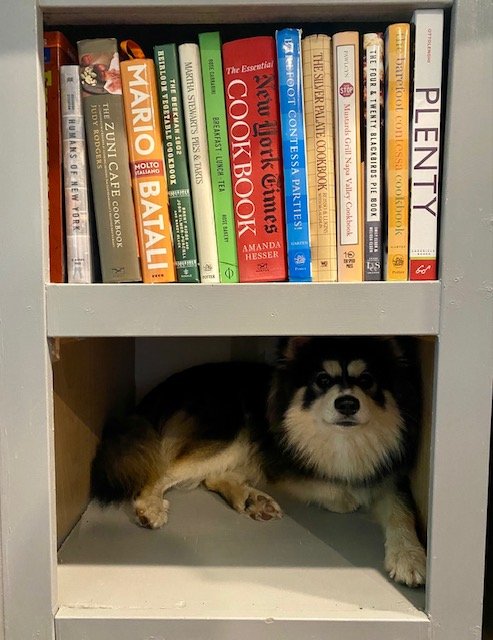

Today’s mascot is the adorable Shackleton. There are still a couple days open, so if you’d like your favorite bookish animal buddy to be featured, email us and we’ll work it out. (This program was inspired by a similar program on the excellent Tennis Podcast.)

Thanks again to everyone, and welcome back!

Today’s mascot

Say hello to today’s official ToB mascot Shackleton, nominated by 2022 ToB judge Jennifer Murphy! According to Jennifer, Shackleton (named after the explorer) is a Pomsky, half husky, half Pomeranian. A lover of people and other dogs as well as nature and alone time, Shackleton is tireless, hilarious, lawless, and he lives for “treatos” and ripping plants out of the ground. Also, he is a voracious reader: He finds books delicious and he reads with his mouth, taking in every word. In fact, when Jennifer was a judge for last year’s ToB and spent the evenings quietly reading, Shackleton was jealous of the books, pawed at them, and howled until she stopped reading and paid attention to him—a ritual that continues to this day. All hail, Shackleton!

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.