Mercury Pictures Presents v. The Book of Goose

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 10 • OPENING ROUND

Mercury Pictures Presents

v. The Book of Goose

Judged by Christina Orlando

Christina Orlando (they/them) is the books editor for Tor.com, where they get to be a book nerd all day. They are a 2019 recipient of Spotify’s Sound Up grant for people of color in podcasting and a 2021 Publisher’s Weekly Star Watch Honoree. Christina currently resides in Brooklyn, NY, with their queer found family. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “I work for Tor Publishing Group so probably should not be assigned Manhunt, even though it fucking rules. I also have been a very public advocate for Babel, also because it fucking rules, but there’s some documented bias there.” / christinaorlando.com

We begin with a death, which is honestly one of my preferred ways for books to begin.

Beginning with a death means we’re existing mostly in memories, which can be a tricky thing. The Book of Goose’s Agnes admits this—“between facts and memories I always trust the latter”—acknowledging that we’re not necessarily here for truth, but instead for the effect left, the imprint of the events that are to follow. And indeed, The Book of Goose explores storytelling and fabrications, and how they can both make and ruin a life.

The book centers on Agnes and Fabienne (victim of the aforementioned death, later on) and their childhoods in rural France in the early 1950s. The landscape is devastated after the war, and neither Agnes or Fabienne have much beyond each other. They bond in the way only girl-children can: intensely, with deep understanding and need for each other, attached at the hip despite adults not being able to see what strings could possibly be holding them there.

Out of boredom one day (and perhaps an instinct to cause trouble), Fabienne decides they are to befriend M. Deveaux, the local postmaster who has lost his wife, by saying they’re going to write a book and asking for his help with it. Fabienne decides she will make up the story, Agnes will write it down, and M. Deveaux will serve as editor and publisher. “We were not liars,” Agnes states, “but made our own truths, extravagant as we needed them to be, fantastic as our moods required.” What begins as (and arguably remains) a game catapults young Agnes to childhood fame. Fabienne’s decision to only put Agnes’s name on the manuscript means that it is Agnes who is brought to Paris to meet with publishers, it is Agnes who gets attention from the press and photographers, and Agnes who is pulled away, causing a trench to form between the two girls.

The book’s prose here is devastating, with truths laid out so eloquently I found myself stopping to take a breather, often.

Fabienne is a hellfire of a child, a girl who burns furiously in a way that the world around her—a world made for polite girls who play nice—cannot possibly handle. In a modern world, she’d be a saint—neurodivergent, probably, and the type of character I could easily see in a more modern setting as a sort of Nancy Spungen, It-girl figure, drawn to the darkest and grimiest parts of life. I felt her deeply, understood instinctively the storms she held within her but could not speak of. She could only ever be smothered by her circumstances.

The book’s prose here is devastating, with truths laid out so eloquently I found myself stopping to take a breather, often. While reading I thought of the many friends I had lost, friends I thought would be forever, and the cruelty of life that forces us to grow up. It is no small feat to capture the love and devastation of childhood friendships turned sour. The Book of Goose is, in short, a most beautiful object.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

In a similar vein, Anthony Marra's Mercury Pictures Presents revolves around storytelling. Within the first few pages of Mercury Pictures Presents, Marra deftly defines the cinema as church: It is a place we go to worship greatness and beg for salvation from our current circumstances—and it is the place where Maria goes with her father instead of church on Sundays. During the rise of Mussolini, Maria’s town in Italy is busy with political activity, with the movie theater being a respite: “…and it seemed outrageous to Maria that the actors on-screen would remain impervious to the drama playing out in their audience. She envied them their blindness.” The screen is an untouchable god until it is set on fire by Blackshirts, changing Maria’s life forever. Later, in an attempt to save her family from the politics she can’t fully understand as a child, she burns records she finds in her father’s office—the remnants of which are later found. Her father is arrested. Unable to save him, Maria and her mother make their way to Los Angeles, where the bright lights of Hollywood come to call.

We flit between Maria’s story at Mercury Pictures in the years leading up to America’s involvement in WWII, her father’s incarceration in Italy, and the lives of others at the studio—Maria’s Chinese-American boyfriend Eddie and the impossibility of leading roles due to his race, and studio’s founder Artie arguing before Congress over the importance of depicting reality on screen and the damage censorship can do to storytelling. There’s even a cameo from Bela Lugosi. The novel has a lot to say about propaganda and the influence of art in wartime, cultural mythmaking, and the craft of filmmaking itself—clearly we see the many hands that come to put a film together, invisible in the final onscreen product and undervalued as a result, but vital all the same.

I thought, at first, it was a mindset thing—these books were given to me to read over the holidays, perhaps I was just too burnt out to pay attention.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t engaged by this book. I thought, at first, it was a mindset thing—these books were given to me to read over the holidays, perhaps I was just too burnt out to pay attention. Because I know this about myself, I knew that this wouldn’t allow me to make a completely fair judgment of the book. So I tried again later, attempting to set myself up for success—only to again find myself uninterested in continuing, letting my eyes go fuzzy over the words. There are a lot of things that are lovely about Mercury Pictures Presents. I just didn’t like it. The prose was not compelling me forward in the way that The Book of Goose had, I did not feel particularly attached to the characters. There are lots of people who loved it—I just didn’t find it as beautiful or moving as another story about the immigrant experience at a film studio that came out last year, Nghi Vo’s Siren Queen. (To be clear, I technically work for the publisher of this book, but I don’t actually work on the books or influence their production—I just write about them for a website.) With a little distance, I am able to say that though Mercury Pictures Presents is crafted well and conveys the emotions and messages that it intends to, it just wasn’t a style that resonated with me.

These two books could not have been more different—where The Book of Goose is lyrical and lofty, Mercury Pictures Presents does its work in the details. Both are historical fiction but it matters less in Book of Goose, where emotion takes precedence. The scope of Mercury Pictures Presents is vast and sweeping, whereas Book of Goose is intimately focused on its two girls. At the end of the day, The Book of Goose’s profound prose won me over—as evidenced by the many pictures of its pages that now live on my camera roll, stored there for me to return to when I need them, which I inevitably will.

Advancing:

The Book of Goose

Match Commentary

with Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile: Judge Orlando didn’t connect with Mercury Pictures Presents, a novel I know both you and I are fond of. And I like the way they just accept the fact and move on. They spend a little time trying to figure out the reason, but the truth is there doesn’t need to be a reason. Sometimes trying to find a reason you didn’t like a novel is like trying to find a reason you didn’t fall in love with somebody.

John Warner: Mercury Pictures Presents is one of those books where our eyes locked across a crowded room, we moved toward each other, embraced, and did not let go until I’d finished the book. I’m not sure I could give you the reason why I had this experience, but it was one of my favorite books from last year.

Kevin: When my first novel came out it received a particularly negative review in a large West Coast newspaper. And the reviewer said something like, “Guilfoile is the kind of writer who feels compelled to tell you that a character eating dinner in a restaurant ordered the butternut squash ravioli.” And I remember thinking that was the dumbest thing I had ever read. There were 100,000 words in my novel, only 900 words in the review, and that was what the reviewer wanted to talk about?

Of course, I was missing the point and nearly two decades of the ToB have helped me understand why. That reviewer simply didn’t connect with the book. But unlike most readers (and very much like Judge Orlando), the reviewer was contractually obligated to finish it and then talk about it. I think we all remember from school that finishing a book you don’t like can be a slog, and subsequently discussing it can be torture. When that scene in the restaurant arrived, the reviewer was resentful of these characters and was annoyed by what they ordered. That was still eating away at the reviewer’s prefrontal cortex when it came time to write the review, and it became one of the reasons not to like the book. But it wasn’t a reason—the reviewer didn’t know how to tell you the reasons. It was a rationalization.

Incidentally, butternut squash ravioli was what my wife always orders at one of our favorite restaurants. Sometimes when you write 100,000 words, a few of them are intended for just one person.

John: This is one of the reasons I don’t write book reviews. I need to maintain my right to stop reading a book I don’t want to read, and believe it or not, coming from someone who spends so much time talking about books, I don’t have sufficient trust in my critical faculties to make a judgment on a book where that judgment is required.

Don’t get me wrong, I have lots of opinions and know my own tastes pretty well, and will tell you why I did or did not connect with a book, but a review feels like a responsibility to me that I just don’t want. When I write about books in my Chicago Tribune column or my Substack, you’re likely to hear what I call an “enthusiasm,” where I’ve read something and want to talk about it. In fact, I wrote an enthusiasm about Mercury Pictures Presents.

Marra is someone who is going to write a lot more books, so at least there’s that solace.

Kevin: I am now picturing you walking around a table like De Niro in The Untouchables, baseball bat in hand, going on about your “enthusiasms,” which include Mercury Pictures Presents. I am wearing a tuxedo, stuffing my face with pasta, and grunting in agreement.

The Book of Goose moves on for discussion in the next round. On Monday, Booker Prize winner The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida meets Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance, which both of us listed among our pre-tourney faves.

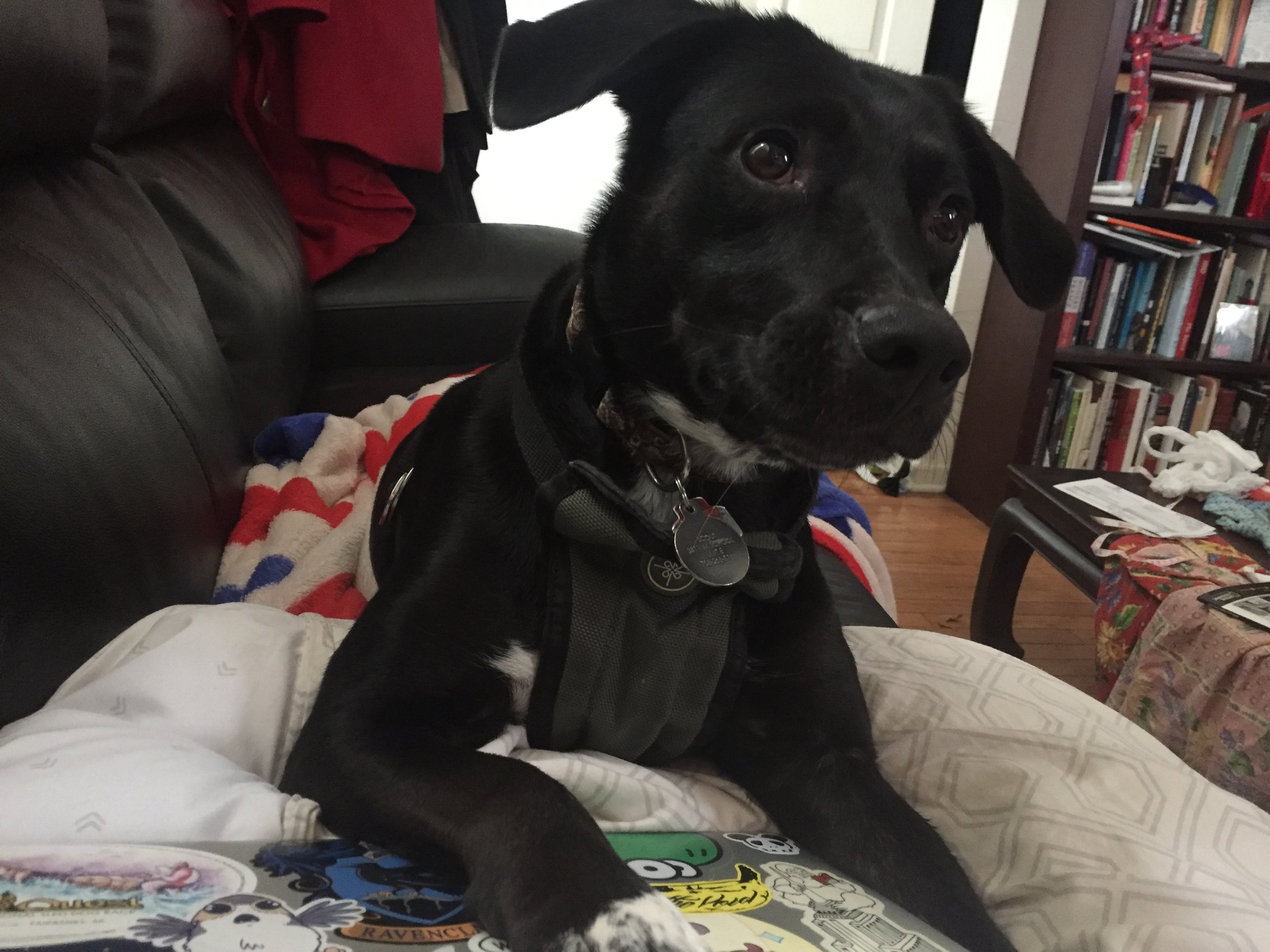

Today’s mascot

Today’s ToB mascot is Scout, a black Labrador mix, brought to us by Elisa S.! Elisa says Scout has two modes: sleepy snuggle/weight-blanket time or jumping eight-foot fences. Scout is a loving dog but she's a lot of dog and would devour books, literally. Elisa says her name has an unusual bookish origin: “Our late dog was named Atticus, not from To Kill a Mockingbird, but from Ancient Rome; Atticus was Cicero's friend. When we were looking for a new dog, we found Scout's picture at a shelter, and she looked like a smaller version of Atticus. With her name, it was like a sign from the universe.” Si vis amari, ama! Welcome, Scout!

Want your bookish animal buddy featured as a Tournament of Books mascot? There are still some slots left. Here are details on how the program works, and if you’re interested please email us and we’ll work it out. (This program was inspired by a similar program on the excellent Tennis Podcast.)

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.