The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida v. Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 13 • OPENING ROUND

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida

v. Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance

Judged by Adam Dalva

Adam Dalva’s (he/him) writing has appeared in the New Yorker, the Paris Review, and the Atlantic. He serves on the board of the National Book Critics Circle and is the senior fiction editor of Guernica magazine. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “Tess Gunty. And I’m friendly with Yiyun Li.” / adamdalva.com

Strange, after decades of omnivorous reading, to stumble onto an unprecedented experience. But I’ve never, before the Tournament of Books, hoped that a book would be bad. I even root for my enemies’ work in the name of art. My dilemma set in because I read Shehan Karunatilaka’s The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida first, carefully, and had a blast. It took two weeks. Despite occasional hand-holding on the part of the eponymous narrator, the winding plot, preponderance of characters, unique structuring, and pleasantly chaotic voice took some acclimation time.

The narrative: Our titular Sri Lankan photographer is dead. He comes to in a sort of Bardo-ish purgatory with a bureaucratic organizational structure and is given seven ghostly nights to solve his murder, shepherd a non-MacGuffin-ed box full of damning photographs of state violence into the right hands, and deal with his loved ones, with his best friend Jaki a particular highlight.

I sat down and read it in three-and-a-half hours, regaining myself only when I finished.

The magnetic second-person voice, like the lead, is impossible not to fall for.

You dumped everyone who ever saw you naked. Abandoned every cause you ever fought for. And did many things you can’t tell anyone about.

If you had a business card, this is what it would say.

MAALI ALMEIDA

PHOTOGRAPHER. GAMBLER. SLUT

There are occasional weak moments. The book’s first half is a bit tricky, as it revs up all its technique and moves between “reality” and the afterworld. The irreverent tone sometimes feels misaligned with the pathos for Almeida that I was experiencing as a reader. Nevertheless, Seven Moons is a Bulgakovian achievement, told from a teeming afterlife of interstitial titles and constant invention, with compulsive, rhythmic prose that is sustained throughout.

You never placed a bet you couldn’t win. Which is not the same as not losing. You went in eyes open, knowing all the angles and most of the odds. The odds of winning the lottery are one in eight million. The odds of dying in a car are one in our thousand. And, according to Mr. Kinsey, the odds of being born homo are one in ten.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

And then, hoping for the worst, I turned to Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance. In a way, I was expecting it to be inferior. Seven Moons is a Booker Prize winner. Notes is a book that perhaps signals, with its floating life preservers and bucolic swimming pool on the cover, something more casual. I sat down and read it in three-and-a-half hours, regaining myself only when I finished. I needed the bathroom, then a glass of water. The kinetic achievement of Alison Espach’s plot is remarkable, in defiance of its seeming simplicity: Sally is obsessed with her older sister Kathy, whose boyfriend Billy once saved Sally’s life. Kathy is addressed in the second person throughout—and early on, Notes plays its gambit, which is reminiscent of Seven Moons’ business card:

But six weeks later, you were dead.

I’m sorry if that seems sudden to you, but that’s what it felt like to me. That’s what it still feels like even now, fifteen years later. Like poof! Sally, your sister is dead! Now go to church.

The temporal setting is the ’90s, that adolescent time that T Kira Madden has called “the days of private telephone lines, inflatable furniture, Juicy Tubes, America Online.” Indeed, Sally soon enters a harrowing dynamic with Billy, who is persona non grata after Kathy’s death, but reaches out on AIM. Years pass and their relationship grows complicated, but the book retains its sense of humor and scene, especially in its supporting characters:

“’I hope you don’t mind,” Valerie said, “I’m addicted.”

Valerie had recorded the sound of her own dishwasher before she went to Disney, so she could listen to it in the hotel. And I’ll admit, it was nice. Easy falling asleep like that, right next to Valerie, knowing that all her mother’s dishes would be clean by morning.

There are issues. A subplot about friarhood—a sentence opener I’ve never written—mainly serves as time filler, but certain scenes—a dead seal on the beach; a tree that needs to be felled—have stuck with me.

The language of grief is ugly, denial-filled, and imperfect. Which is the difference, perhaps, between a book-as-dream instead of a book that contains nightmares.

So, both books were good—how to choose? I’m one who roots for the underdog. My March Madness bracket is busted within seconds every year. I am a Knicks fan. Cool Runnings makes me cry. But despite Notes matching up with a number-one seed, Seven Moons’ journey to the Booker Prize was remarkable, a genuine success story for a bold, brave epic. So, I read Seven Moons again, kind of. I read Chats With the Dead, the original English-language version of Seven Moons that was published in India by Hamish Hamilton in 2020, acquired by a UK indie, and rewritten for the British audience. A further problem set in when I realized I like Chats With the Dead a bit better, though the changes are marginal—it’s a slightly floatier text and less explained, which felt more aligned with Almeida’s experience after his death.

Indeed, my preoccupation, as my decision came due, was with thoughts on character mortality, and the way both novels address their dead subjects directly. I, in recent months, have become interested in art that captures the complex feeling of loss: work like Nick Laird’s poem “Up Late,” or Amy Hempel’s story “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Was Buried,” or Brandon Taylor’s essay “All About My Mother.” The ugliness of death and the ensuant irrationality of it is a point in favor of Seven Moons, but sometimes, though I admire the novel’s irreverence, it resulted in disconnection. In Notes, the grief dominates the novel, distorting everything in a way that felt fitting, if at times a touch over-constructed. In the end, it came down to a question of fluency in what, in “Al Jolson,” Hempel calls the language of grief versus fluency in the language of literature. The language of grief is ugly, denial-filled, and imperfect. Which is the difference, perhaps, between a book-as-dream instead of a book that contains nightmares.

But maybe that’s complicating things too. I’m pretty sure I also picked the one I liked best.

Advancing:

Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance

Match Commentary

with Rosecrans Baldwin, Meave Gallagher, and Alana Mohamed

Rosecrans Baldwin: Hi everybody. I noticed the commentators were having so much fun, I decided to jump out from behind the organizers’ curtain!

Meave and Alana, let’s start here: have you ever gone into a book hoping it will be bad? When are situations where you go into a book feeling one way or another about it, rather than neutral?

Meave Gallagher: I am so committed to high dudgeon I’ve agreed to read utter nonsense for my book club just so I could prove the authors wrong. This necessitates greater investment in the text than in a book I might like, which is perverse, but the resulting righteous indignation feels so good. There’s nothing like spite as a motivator.

Alana Mohamed: Oh, Meave, we are cut from the same cloth. I remember taking extensive notes on a certain celebrity psychologist’s book just to prove a point to a (poorly selected) paramour.

Rosecrans: I respect that move.

Meave: I deeply respect that move. This judgment, however, reads like Judge Dalva wanted to dislike Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance because he felt—obliged?—to give The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida the win. I totally relate to his reading a previous version of Seven Moons just to be sure he wasn’t missing anything, which is questionably “fair” in that Chats With the Dead isn’t the book in play, but I get where he’s coming from. Alana, you said earlier that you often question your initial negative reception to a book, which sparked some debate among the Commentariat. How far has that questioning taken you? I couldn’t get into Seven Moons, and since I didn’t have to read it, I felt fine abandoning it. Now I feel like I owe it another try, or at least like I should read some Sri Lankan literature.

Alana: I relate to Judge Dalva and applaud his efforts, but I have never gone quite that far. I wanted to like Seven Moons more than I did because the voice was so charming and the use of second-person address was ballsy. But even without doing some additional reading, I do think it’s useful to question my own reactions to a book. It helps me understand myself as a reader, or what it means to write a “good” book.

Meave: Taste is subjective! It is fine to discard books! A treat, even. Other times, introspection is valuable.

Alana: Very true! It felt great being done with that psychologist’s book.

Meave: Are there any places/cultures/eras whose literature you’re especially moved to explore right now? To name but three on my endless list: Armenian, not (explicitly) about the genocide; Indigenous/First Nations; African, outside of South Africa or Nigeria. My reticence to work harder to engage with a book that doesn’t immediately click sometimes embarrasses me: Like, why don’t I like Clarice Lispector? She’s internationally beloved!

Rosecrans: I know I’ve been seeking out books from Asia—outside of Japan—just to try and fill in some huge gaps in my reading.

Alana: Sometimes you have to come back to a book when you’re ready for it, sometimes there’s just no point. Generally, I feel that I should be reading more of everything. I often wonder how culture shapes my reader biases. The elements of Seven Moons called out, “the winding plot” and “preponderance of characters,” reminded me of the Bollywood movies I grew up watching and how they seemed to go on forever. I always hated that I liked the zippier American movies better.

Meave: As I understand it from living vicariously through my husband, being part of a diaspora is a real push-pull situation, culture-wise. Not to presume too much.

Alana: Of course! And there are biases in both directions to address. Like Judge Dalva, I expected Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance to be “more casual” because its cover felt very American-family-vacation to me. I literally judged it by its cover. Do you have any reading preferences that you don’t love?

Meave: Um. I read dark academia to work out (some of) my class hangups. It never works and most are mid at best, but I keep drinking from that bitter well.

Rosecrans: Man that sounds like a horrible well. To get back to the judgment, the judge’s favoring of Notes looks to be connected to his sense of disconnection with Seven Moons. If I were a judge, I can’t imagine picking a book to advance that I didn’t connect with, whether on an emotional level, an intellectual level, even if I admired it.

Alana: It’s hard to overlook emotional connection. Isn’t that what art is all about? Since I’m a reader who loves to doubt herself, I expect I could make a case for either book, but it feels dishonest not to pick the book that resonated more. Otherwise there’d be no difference between a human and a machine judge. But this is also the tricky thing about these matchups; what’s emotionally resonant today may not be tomorrow. Has that ever happened to you, Meave?

Meave: This reminds me of choosing The Lacuna over Wolf Hall to win the 2010 ToB. I loved The Lacuna then, but haven’t touched it since. Meanwhile, I’ve read Wolf Hall three times and Bring Up the Bodies twice.

Rosecrans: Good lord!

Meave: To me, a good judge chooses the book they liked better, but they interrogate that choice, so people who disagree with the decision can (maybe?) respect how the judge came to it. Anyway, you’re right; the art has to move you.

Alana, I don’t think of you as a reader who likes to doubt herself so much as someone who wants to give books a chance to be great. It’s a hopeful attitude, one Judge Dalva seems to share and I find admirable, if potentially exhausting. But what do we ever have besides hope and hard work?

Alana: You heard it here, folks: Make reading a chore, it’s all we have.

Meave: And you all thought I was mean.

Rosecrans: Never! Let’s turn it over to the Commentariat for further thinking. Looking ahead, tomorrow we’ve got the idealistic game devs of Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow taking on Dinosaurs’ idealistic Arizonan bird-lover. Best of luck to Judge Olivia Waite!

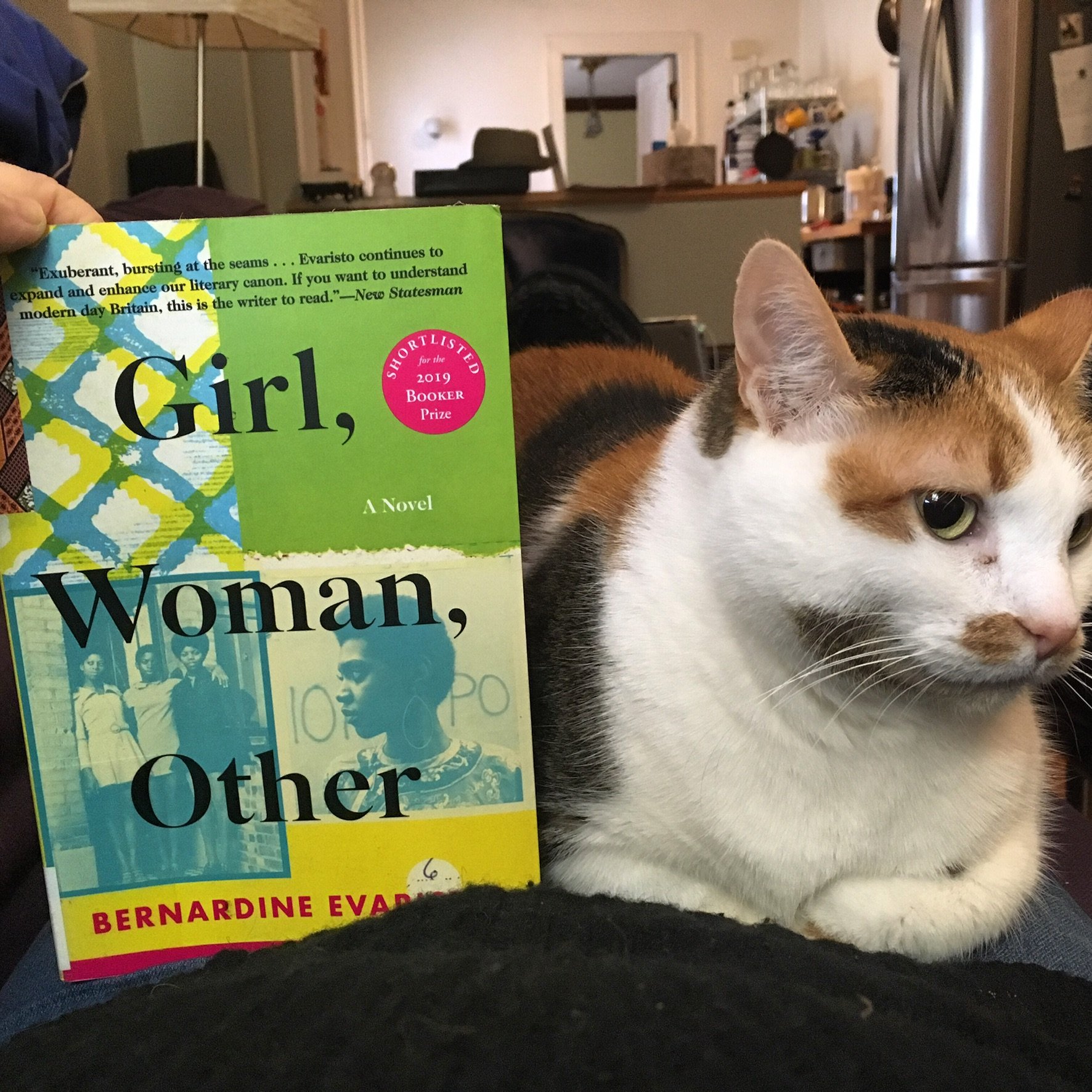

Today’s mascot

Today’s mascot comes to us from Cheryl F. “This is 12-year-old Ginsburg (RBG, not Allen), whom we adopted from a shelter 10 years ago. She loves books, especially ones with sharp corners to rub against her furry face. She tends to prefer fiction but loves a good essay collection. Here she is with some of her (and my) favorite ToB entries.” Hooray for Ginsburg!

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.