James v. The Book Censor’s Library

The 2025 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 7 • OPENING ROUND

James

v. The Book Censor’s Library

Judged by Molly Templeton

Molly Templeton writes a lot of things for Reactor Magazine, including news, reviews, and “Mark as Read,” a column about the reading life. Her writing has also appeared in BuzzFeed and Esquire, and she was the arts and music editor for the Eugene Weekly for too many years. A former bookseller and publicist, she currently works for the Ursula K. Le Guin Foundation. Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / mollytempleton.com / Bluesky

In the words of the great Cari Luna: “Aw, fuck.” This was her thought when she got her 2022 assignment, and mine this year. I did not want to read James. I generally do not want to read literary sweethearts until their time as sweethearts has passed, and I can read them with only lingering awareness of their initial popularity. It’s a little contrary, but it’s also a feeling that comes with being a perpetual rooter for the underdogs. I was very interested in The Book Censor’s Library.

I reread The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn first. Had I a better idea of what I was getting into with Book Censor’s, I might also have read or reread Zorba the Greek, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1984, Fahrenheit 451, and Pinocchio. It was quickly very apparent to me why—luck of the bracket aside—these two books were paired: They exist directly because of other books. You could say that all books exist because of other books, but these have very clear ancestors, which is not always the case. They also play with narrators and voice, with who is telling the story and to whom.

Things I thought about while reading Book Censor’s: White rabbits. Whether I ought to find a copy of Zorba the Greek. The expansiveness and limitations of fairy tales. The absurdity of authoritarian approaches to art. The power the authoritarian might wield regardless of his own absurdities.

Things I thought about while reading James: How it might make me, however resentfully, better appreciate Huck Finn. Fanfiction and the transformative powers therein. What it means when people call prose “economical.” How many Percival Everett books I could potentially read before I had to write this judgment. Whether or not it was a terrible idea to try to read them all.

The Book Censor’s Library is about a newly appointed book censor, who lives in a future where the Founding Fathers of the governing System “had decided that imagination was the origin of all past evil.”

“From then on,” Bothayna Al-Essa writes, “the System’s aim was to create a human being who, after a long day’s work, wanted nothing else but to go home.”

The System allows books that support the system, books with language that offers “an impenetrable surface.” The censor’s job is to read books and flag violations. (Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, for example, “contradicts logic.”) But to become aware of violations is to become familiar with them, and with all the things language has hiding under its shining surface. The book censor is troubled, and all the more because his vibrantly imaginative daughter won’t stop telling stories of her own.

James is about James, also known as Jim, the enslaved man who travelled with Huck Finn in Twain’s famous, beloved, oft-argued-about novel. Percival Everett’s James is the opposite of the book censor: well-read thanks to the judge’s library, he has arguments with Voltaire and Locke in his head (or in his hallucinations) and instructs Black children in the language they use to speak to white people. He is as far from the book censor as one might get, steeped in words, in how they work and how they’re used for or against things. And how they work for or against him, as he, Huck, and a cast of familiar and freshly invented (or historical) characters travel the Mississippi.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

I’m trying to maintain suspense as to my judgment, but it’s difficult. I haven’t stopped talking about James since I finished it. I subjected my partner to a lengthy, one-sided conversation about the words used to describe James at different points in the book—slave, criminal, thief, murderer—and the way no word, no label, is without context, how the context the novel provides renders all of these labels ignorant, foolish, bitterly wrong, even when technically accurate. I went on about transformative narratives, about how richly and thoroughly James shifts the footing and the focus of Huck Finn, how it is not writing against that book but alongside it. I thought about Wicked (the book) and transformative versions of American literature. I thought about America, and how it might transform.

The Book Censor’s Library is a “rallying cry against censorship,” as one back-cover blurb says. It is also a reminder that novels are not just the words on the page, but the connections and history an author is working with and within—and that each reading involves the biases and interests and specific context of the reader. It is fable-like and transformative in its own way; it might be terribly relevant to people in distant parts of the globe. The author has a bookstore in Kuwait and deals with the staff of the Ministry of Information. In America, we face individual or organized book-banners who have never read the books they wish to ban. There are too many other examples. “Our duty as book censors is to block all avenues of interpretation,” says the First Censor. It’s satire, but it can also be read as an earnest warning about authoritarianism, control, language, and imagination.

Satire is one of the tools in Everett’s arsenal, along with farce. James is also sometimes a near-thriller, sometimes something like a buddy comedy, sometimes (and also always) a horror story. James tells his own story, at some remove, but it is oddly easy to forget that he is his own narrator. “Safe movement through the world depended on mastery of language, fluency,” Everett writes early in the book. He is giving the Black kids a lesson in code-switching:

“White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them,” I said. “The only ones who suffer when they are made to feel inferior is us. Perhaps I should say ‘when they don’t feel superior.’”

This concept is both explained and demonstrated, and while the scene is only a few pages long, it snagged me. It seemed repetitive. Why show and tell? Who needs this concept this thoroughly outlined? When he and the other enslaved people shift their language in the presence of white people, the reader recognizes who the audience is. But who is the imagined audience for his longer narrative?

I’m a grump, sometimes, but I’m a very earnest reader. A ruder assessment might say gullible. To some degree, I read James straight, as a beautiful revisioning of a classic novel that illustrates how many different ways there are to tell a tale—and how a long-told tale might be changed.

But that early scene, with all its shifting language and elaboration, stuck with me. James is serious and funny, heartfelt and biting, playful and terrible, sometimes all at once. I kept coming back to my thoughts about this book, revising them, and thinking about voice and audience. And also about Erasure, which I read after James. While I would never expect Everett to repeat himself, is there, maybe, a little bit of Erasure here? Is Everett, in part, giving American white audiences what we expect and reward: a transformative book about Black suffering and white guilt, with a noble and heroic (and eventually violent) figure at its center? But while also gorgeously imagining James himself? I don’t know. I can’t say he is. I can’t say he isn’t. I can comfortably say that no book is just one thing.

A scene from Huck Finn is reversed here, and maybe telling: Tom and Huck think they’re playing a trick on Jim, who’s entirely aware of their shenanigans and turns it around on them, though the boys are none the wiser.

It seems to me that Everett has written perfectly in two voices at once: one relating the powerful experience of a man not previously given full consideration, and the other the voice of a writer who understands his audience and how to tell his story in order to elicit the desired response. It’s the same voice, but in different registers. Thinking about James this way makes me want to start it again from the beginning.

“When people come to the work, they get what the work offers. And however you get them there, it’s OK,” Everett told the Guardian. In the same interview, he said, “I might be interested in a really scathing review.”

Sorry—but not at all sorry—to disappoint.

Advancing:

James

Match Commentary

with Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner

John Warner: Like Judge Templeton, I am a very earnest reader. I am more than willing, eager even, to just let a book take me in in a way that causes me to let down my critical guard and just freely ride along as it connects to some deep pleasure center in my brain. This makes me a mark for all kinds of books ranging from Reacher to Knausgaard, but by god is it a pleasurable way to go through life.

If a big or praised book does not cause this shift in me, I’m pretty happy these days to not worry overmuch if the book or author might be “overpraised” (whatever that is), or if I might have a present defect that keeps me from appreciating a worthy work. “Not for me, not at this time,” I think, and I move on.

It wasn’t always thus. I used to take great offense at books that I thought failed me.

Is this just getting old?

James worked on me from the first word to the last. Judge Templeton’s notion that Everett has written the novel in “two voices” strikes me as one of the best explanations for my particular pleasure in reading this novel that I’ve seen.

Kevin Guilfoile: That’s my favorite line from the judgment, as well. You were the person who first turned me on to Everett, and I can’t even remember now which book I read first, but I had a similar reaction as Judge Templeton: I need to read them all, right now.

John: Readers may be interested in my “definitive, entirely subjective ranking of Percival Everett’s novels” (that I’ve read). James comes in at number four, which may strike some as a bit low, but is mostly a testament to my Everett fandom and the fact that I’ve been badgering the ToB organizers to include a book by him every year he writes one, which is just about every year. I think Everett wrote the exact book he intended, but personally, I’m even more enthusiastic when he weirds-out (to use a technical term) even more.

Kevin: You and I are not the deciders when it comes to making the ToB shortlist, but we are inputters. And while making the case for James this year, it was pointed out to us that Everett has had four books in the ToB. That surprised me, I guess because I read every one of his novels anyway. And I get that we don’t want to have the same authors in competition every year—we don’t want to have a repertory company of Percival Everetts and Sally Rooneys that just duke it out again and again. This novel was just undeniable for me, though.

I read Huckleberry Finn when I was very young—maybe third or fourth grade? My family was driving from Pittsburgh to Bradenton, Fla., and I shared the back seat with my siblings and had nothing to do but read, which was fine with me. I followed Huck and Jim on their journey down the Mississippi while I was making a parallel journey south, living their adventures vicariously, and I was just loving it.

In the past I’ve voiced the idea that every time we pick up a novel we are trying to recapture the experience we had when we first fell in love with reading. Huckleberry Finn was one of those experiences for me. But it was just an adventure story at the time. Slavery was an evil but abstract artifact of history. I had no understanding of how it affected my 10-year-old life in 1970-something. To revisit that story with a writer I love, a writer who puts that adventure story I also loved into a context for adult me, one that is playful and meta and contemporary, but also quite serious, is just delicious.

John: Indeed, Everett takes Twain in general and Huck Finn in specific quite seriously, though also without reverence, which is maybe a good attitude to have toward literature in general.

Kevin: OK, we are off and running with the National Book Award winner moving ahead to the quarterfinals. On Monday, Headshot by Rita Bullwinkel gets in the ring with Kelly Link’s magical realist fantasy The Book of Love. Judge Hannah Bonner will be making the call.

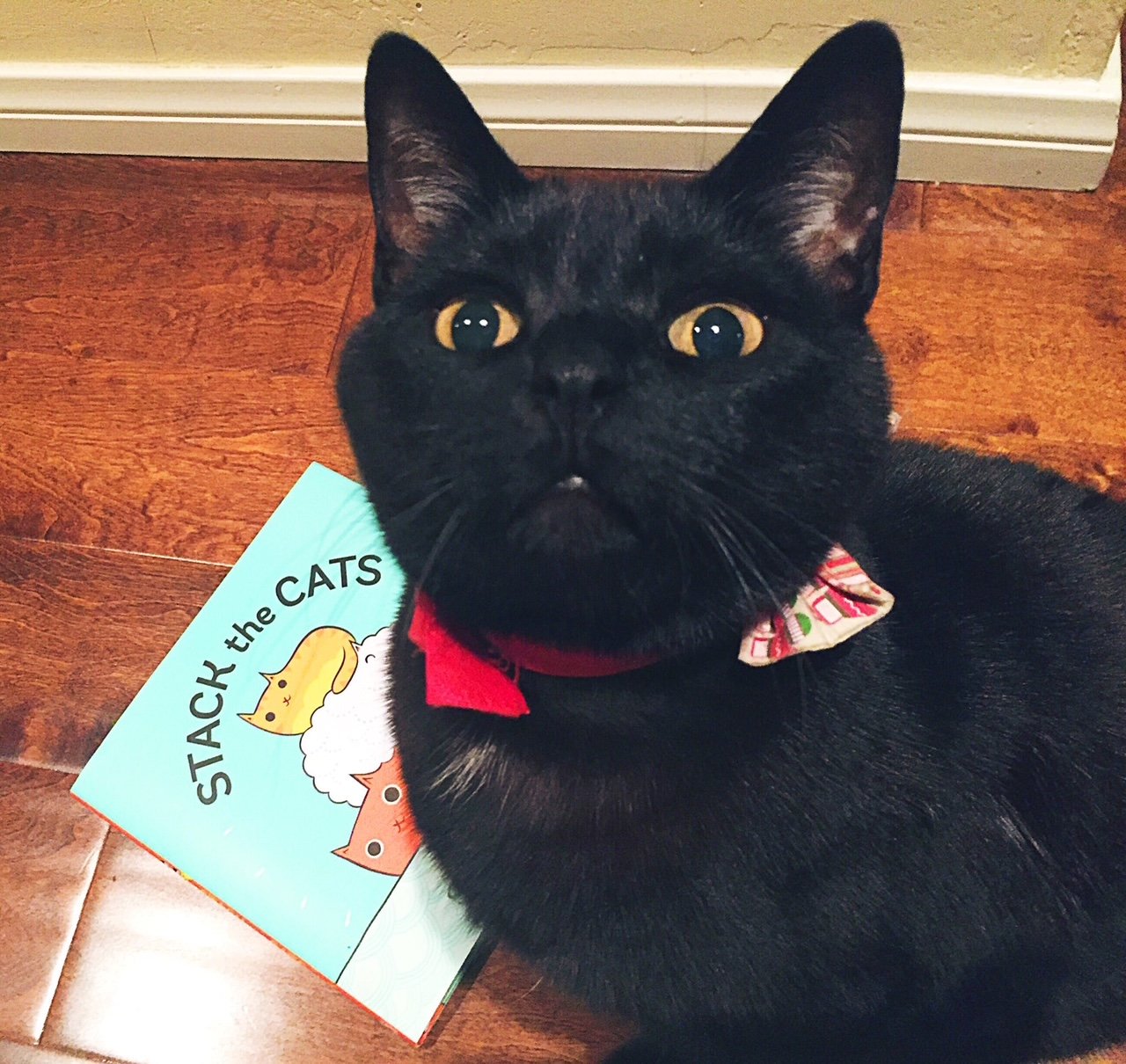

Today’s mascot

Nominated by Susie, this is Violet, a black cat with a white dot at the end of her tail. Like an angler fish, it is what people notice first—but her real charm point is her tiny little nose. She is simply the sweetest cat in the world, adopted in 2012. Consistently for these 13 years, I have mistaken every dark bag, shoe, and T-shirt for her. She prefers uplifting books and hates Canada geese for some reason.

Bonus pet: Sid the society finch, named for the owner of a surf shop in Rhode Island; Sid P. Finch was adopted a couple months ago and remains completely illiterate but rather musical.

If you’re interested in nominating a pet as a mascot for this year’s Tournament of Books, contact us for more details. (Please note, this is a paid program.)