Headshot v. The Book of Love

The 2025 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 10 • OPENING ROUND

Headshot

v. The Book of Love

Judged by Hannah Bonner

Hannah Bonner is the author of Another Woman (EastOver Press, 2024). Her criticism has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Another Gaze, Cleveland Review of Books, Literary Hub, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Senses of Cinema, and The Sewanee Review, among others. She lives in Iowa. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “Kaveh Akbar is one of my supervisors at the University of Iowa, but only as someone to go to if I have questions about a student.” / hannahruthbonner.com / Instagram

For many years, I was a long-distance runner. I structured my days around interval training, weightlifting, and hot yoga sessions at a small boutique studio nestled next door to a steakhouse in the midsized Midwestern town where I lived. I ran in rain, windstorms, and subzero-degree weather. When it snowed, bald eagles surveyed me from their large nests in oaks lining a small, manmade lake.

In other words, for many years I knew a lot about endurance and a little about pain. The blisters or shin splints were annoyances rather than deterrents. I ran my first marathon on a chilly April morning in a thin T-shirt without gloves or a hat. Heading into the race, I was nursing an injury and couldn’t walk afterwards without wanting to throw up for almost a week. Perhaps my own complicated relationship to running—and pushing my body to extreme limits under the guise of strength and health—makes me predisposed to Rita Bullwinkel’s prismatic Headshot, told from the oscillating perspective of eight teenage girl boxers at a championship tournament in Reno, Nev., as well as Kelly Link’s The Book of Love, a sweeping epic that requires the same intensity of attention as any physical skill.

The precision of detail here catapults me back to the years when I clocked 60 miles a week.

Headshot is written in the present progressive tense, which gives the book an electrifying immediacy. The novel opens as…

Andi Taylor is pumping her hands together, hitting her own flat stomach, thinking not of her mother sitting at home with her little brother, not of her car, which barely got her here…not of the four-year-old she watched die, the four-year-old she practically killed, and his blue cheeks.

With breathless propulsion, Headshot plunges us into the depths of each character’s interiority. Like a carousel, we spin in and out of various characters’ thoughts, chapter by chapter, culminating in a choral array of adolescent voices grappling with both girlhood and violence. Though the novel’s syntax moves swiftly from present to future and from one fighter’s strike to another’s, Bullwinkel also peppers her prose with specific details that give the story bite. Though Andi’s opponent Artemis is formidable in the ring, when she’s “sixty she won’t be able to hold a cup of tea.” The precision of detail here catapults me back to the years when I clocked 60 miles a week. All my toenails were falling off. I ate pita in the shower because I was never full. I could still hold a cup of tea, but had I ruthlessly continued with my running, I might not have been able to walk to retrieve it.

The Book of Love, like running, is also an exercise in mental endurance. Clocking in at over 600 pages, its chapters contain titles of the names of characters (like “The Book of Daniel” and “The Book of Ruth”) whose lives are inextricably linked. Like the Old Testament, a family tree at the beginning of Link’s opus might benefit all the myriad characters who intersect in both fantastical and mundane ways. The novel follows three teenagers (Laura, Daniel, and Mo) who have returned from the dead and find themselves ensnared in questions of where they’ve been—and what their fate will be. Their music teacher, Mr. Anabin, possesses magical powers and has altered their families’ perception of reality so they think their kids have been on a trip to Ireland. When they return from death to their hometown of Lovesend, Mr. Anabin writes on a chalkboard, “2 RETURN 2 REMAIN,” as if this is some kind of nefarious game. There’s a shape-shifter named Bogomil. Laura and Daniel, when they were put back together from death, have switched ears.

If this story sounds intriguing to you, it is.

But if this story sounds convoluted to you, that’s also true.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

The Book of Love uses mostly dialogue as a means of exposition, and the countless characters and their narrative threads dilute the plot. The world in which this novel exists is hard for me to picture. Perhaps that’s because so much of the novel is driven by dialogue, rather than description. When Link does describe something sensorial, like Bogomil leaving his clothes on Daniel’s porch, they “stank of Bogomil,” and continues,“Someone would have to wash them. To see if that stink would come out.” For a screenplay, such a description would work well, since the actor, setting, props, and costumes all contribute to the atmosphere. For a novel, I understand that Bogomil smells, but of what, I don’t know. Over a hundred pages later The Book of Love does clarify, Bogomil smells of “something burnt and musky and sweet, like a fire that had gone out.” I wish such specificity were the book’s norm, rather than an exception. But even when Laura’s sister Susannah “came up from [a] song like a swimmer from the sea,” this concrete image ultimately tilts more toward the clichéd rather than toward Ezra Pound’s ever-relevant directive “make it new.”

Additionally, while Headshot oscillates between the perspectives of eight different girls, each chapter is devoted to two characters and two alone. It allows us to sink into the characters’ psyches, reveling in their preoccupations, vanities, insecurities, and skill. In The Book of Love, I found myself overwhelmed by the array of relationships that never seemed to skim more than the surface. When Laura reflects that her sister, Susannah, seems fine, she also notes that “there was all the stuff about Thomas, and Malo Mogge being the moon, whatever that meant. Not to mention the fact that Mr. Anabin and Bogomil were apparently in thrall to her, but this was something Laura would need to talk about with Mo. And Daniel.” While the elongated syntax mirrors a mind’s synapses firing on all cylinders, the litany slows the pace (and this reader’s interest) in the narrative at hand. Much later, witnessing a death, the only description of Laura’s reaction in that moment is “[throwing] up on the temple floor.” Readers searching for psychological depth in The Book of Love will be sorely disappointed; those content with fantasy, action, and conversation as a means of plot development will be rewarded.

During each fight, Headshot is formally broken up into short sections. A sentence in one section reads, “The desire to please people is the desire to not be singular.” Though this novel is, at face value, about the paucity of attention given to girls’ sports (“there are no photographers,” it notes at one point), it is also about the performance of femininity and the tensions between how girls are expected to act in and outside of the ring. Rather than get bogged down in exposition like The Book of Love, Headshot trusts a smattering of specifics to draw the reader in and its kinetic form to keep the reader’s attention.

Ultimately, one’s reading experience, and subsequent judgments, are simply about taste, rather than an art work’s inherent worth or success. The Book of Love falls short of what I want my novels to do: to situate me within a world I can vividly and readily conjure. Conversely, Headshot lands all its punches. Bullwinkel pulls off psychological depth and inventive form without sacrificing lyrical prowess. Objectively both of these books are incredible feats (of word count for one, athletic prosody for another), but for this reader, Headshot is the clear knockout.

Advancing:

Headshot

Match Commentary

with Meave Gallagher and Alana Mohamed

Alana Mohamed: Hello, Meave! An interesting round for sure. I was curious what the outcome would be, given that Headshot and The Book of Love are (to me) such different books. What did you think about this matchup?

Meave Gallagher: Both authors are writing from the perspective of teenagers? I got the impression Judge Bonner prefers a shorter book—no way is “[an] incredible feat…of word count” a compliment—but for me, reading The Book of Love was like, after all those short stories (“Prince Hat Underground”!!!!!), Kelly Link raised her arms, stretched, took a huge breath from wide-open lungs, and this big story came whooshing out. Continuing this questionable analogy, Headshot is in a boxer’s stance, tightly and crouched and hunched.

Alana: In looking at the criteria for this judgment, it seems like Judge Bonner valued description and interiority most, giving Headshot the upper hand.

Meave: But The Book of Love is full of description and interiority! Take the judge’s example: Laura doesn’t ask her sister how she is, she remembers things that might’ve made Susannah not-OK and hordes them to speculate about later. I guess I prefer these little reveries to constantly returning to the image of a drowned boy’s “corn dog leg,” which made me increasingly nauseous and resentful of its repetition.

Alana: Judge Bonner flags that Headshot’s focusing on two characters at a time helped readers to “sink into its characters’ psyches,” but the chapters of The Book of Love, told from a singular character’s perspective, made her feel “overwhelmed.” The Book of Love was not my cup of tea, personally, but do you agree that it excels mostly in the realm of plot development via fantasy, action, and conversation?

Meave: I don’t want to get ahead of the game, but Headshot’s tight focus on each character reminded me a lot of Orbital, which we’ll be seeing a few days from now. But it wasn’t exactly all realism and action—the competitors’ discworlds and kidney beans were fantastical, no? Were they more or less fantastical than Mo turning into a bird and a fox and water, and feeling less like returning to his human form each time?

Calling The Book of Love “an exercise in mental endurance” makes me wonder if the judge liked it at all. Reading about Bogomil in the beginning gave me such a strong feeling of dread, I couldn’t read it at night. Headshot didn’t affect me nearly as strongly, though I love Rachel Doricko and her weird-hat philosophy. It takes a lot of attitude to hide how hard you’re trying to stand out.

Alana: Judge Bonner recounting her long-distance running days (eating pita in the shower!) made me realize that it’s partially because teenage striving is so relatable. I am certainly no champion athlete, but I recognize that my young life was full of striving to be acknowledged as an individual. In Headshot, the tournament prize is a means to do that, and an interesting book about this demands a deep dive into each character’s motivations. But I do also think it allows for less exposition in a way The Book of Love can’t afford.

Meave: I’m not sure what you mean: The Book of Love can’t afford less exposition?

Alana: That’s the dynamic I saw being set up by this judgment. I would agree with her that the amount of exposition-through-dialogue is not necessarily the thing that gets me going.

I don’t know that I agree with Judge Bonner that there’s no “psychological depth” to the characters of The Book of Love. While the teens themselves might be unable to articulate their feelings or motivations, readers were granted more insight. I will say I found the dialogue pedestrian in a way that might be fun to see on screen, but also felt a little bit like a parody of teens.

Meave: I will grant that the holes in my memory are widening, but I don’t remember finding The Book of Love’s dialogue overmuch or parodic. Nor do I recall wishing it had less expository yapping. When I think of the book now, I remember the weather, the connection of magic and nature, the magical deals—standard Kelly Link themes on a bigger scale.

And I hate to be a pedant, but “witnessing a death, the only description of Laura’s reaction in that moment is ‘[throwing] up on the temple floor’” is just wrong. Laura brought her mother’s corpse to her mother’s killer, Malo Mogge, and begged her to bring her mother back to life. Instead, Mogge says she can’t bring people back from the dead, and “honors” Ruth by taking one of her ribs and then burning her body. Laura vomits, Mogge “[gives] her a severe look,” and Laura apologizes and begins weeping. “‘My mother,’ Laura said. And could not go on. Ruth’s corpse was burning on the floor of the temple.” I thought it was written pretty sparingly for something so shocking and tragic.

Alana: While the dialogue seemed memorably bad to me, I think I ultimately agree with you that “expository yapping” isn’t the most precise criticism of the book. It might be a shorthand for something lacking on the page—or that the book expects its readers to inspect between the lines of what our teens say and do. I wasn’t particularly motivated to do this if I’m being honest.

Meave: Look, if the novel did not evoke in the reader many feelings without explaining each one, I can’t help that reader. It was not metafiction about Moby-Dick, but Kelly Link just is my kind of author, and I’ll follow her anywhere she takes a story.

Alana: Ultimately, Judge Bonner comparing The Book of Love’s “word count” to Headshot’s “athletic prosody” makes me read this judgment as one more about style than anything else. Which, sure, valid. But I do wish there had been a more serious consideration of what she thought The Book of Love did well.

Meave: I suspect this is a case of “one very right and one very wrong book for the judge.” Too bad for the Link contingent, but for people who like sports whose athletes regularly suffer from CTE, congratulations!

Tomorrow, Judge Jean Chen Ho picks between Martyr!’s obsessive poet and Rejection’s cast of, well, rejects. And lucky you, Commentariat: John and Kevin will be here to lead the discussion—while Alana and I visit the boxing gym, then practice our flying by turning into raptors.

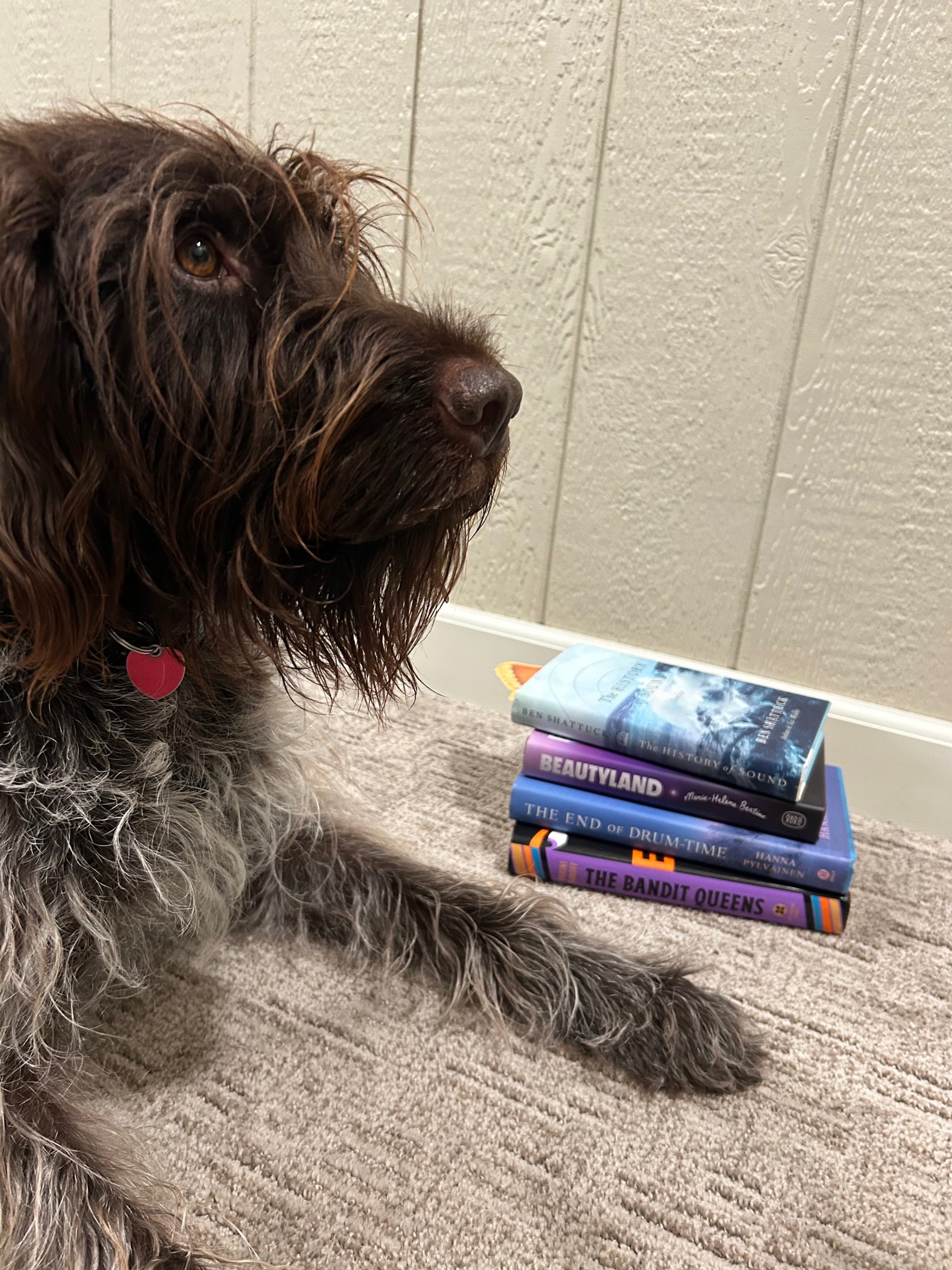

Today’s mascot

This is Copper, nominated by Carrie, who tells us:

He is a Wirehaired Pointing Griffon, aka a “Griff.” We have been his humans for two of his five years on earth.

Griffs tend to be quirky, and Copper is quirkier than most. We do not know much about his early years; he is scared of the kitchen and hardwood floors. Overall, he is affectionate and loving and does all the good dog things.

Copper, being a Pointer was thrilled that the 2023 Rooster winner was The Book of Goose—a bird on the cover! He is disappointed that none of this year’s covers feature a bird but is partial to the magic forest artwork on the Irena Rey.

Copper is very willing to pose with books for Litsy pics. Until he isn't; maybe when the book isn’t on the long list.

Copper appreciates the opportunity to represent and honor his mama who has supported (and been obsessed with) the ToB for many years.

If you’re interested in nominating a pet as a mascot for this year’s Tournament of Books, contact us for more details. (Please note, this is a paid program.)