Sea of Tranquility v. The Violin Conspiracy

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 23 • QUARTERFINALS

Sea of Tranquility

v. The Violin Conspiracy

Judged by Ahsan Butt

Ahsan Butt (he/him) is a writer whose short fiction and essays have appeared in West Branch, Split Lip Magazine, the Massachusetts Review, the Normal School, the Rumpus, and elsewhere. He is currently a senior editor at South Asian Avant Garde: A Dissident Literary Anthology (SAAG). Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / ahsanb.com

The protagonist in Teju Cole’s Open City—not one of the competing books but bear with me—experiences a moment that recalls a memory so strongly that his world seems to double. Remembering becomes like staring into a reflection without knowing where the reflected world begins: “And this double of mine had, at that precise moment, begun to tussle with the same problem as its equally confused original. To be alive, it seemed to me, as I stood there in all kinds of sorrow, was to be both original and reflection, and to be dead was to be split off, to be reflection alone.”

I think this sensation of doubling is what the best literature does. A dead text is, at its best, merely a reflection to be looked at. Whereas a text that’s alive conjures the reader as its reflection, makes you tussle as it does with its concerns, and reminds you, in its most disorienting moments, viscerally, that you’re alive.

Sea of Tranquility is a very Covid book by the author that wrote the Covid book years before Covid (Station Eleven). Its best parts follow a writer touring for a novel about a pandemic as reports of a pandemic begin to break. Throughout, Sea touches on the question of how to live when one has become estranged—whether by distance or loss—and time itself has become weird. The book moves swiftly, gliding along its fragments and short scenes, culminating in a cozy profundity. I read it over two evenings just after New Year’s, as the scene at my window softly whitened.

It’s an engrossing expression of exhaustion, loneliness, and mounting dread made surreal by its nakedness.

Sea is structured around a glitch in time and space with sections spanning from 1912 to 2401. It begins with a reluctant young colonizer in light exile to Canada who walks under a maple tree and is transported for a flash into a blank space that feels vast and interior like a train station where he hears notes from a violin and a whoosh he can’t fathom. A moment later he’s back, and after a quick vomit, stumbles to a cathedral where an incongruous priest asks pointed questions about the flash before this priest who’s not actually the priest sees the real one coming and flees.

This propels us into the mystery, which proceeds at a clip and is well-woven across different timelines. The sections set in 2401 show off Mandel’s elegant world building. We’re introduced to the Time Institute, initially referenced as an academic place to study things like “quantum block chains,” but which takes on a more ominous aura with the reveal of its time detectives and its relationship to the state and law enforcement. The exposition here is finely tuned for genre-twinged literary fiction—suggestive, but not dense enough to bog down the prose.

Sea’s most affecting section, set in 2203, indulges and mines a meta-ness to surreal effect. Olive, a novelist with clear parallels to Mandel, tours Earth for her pandemic novel, recently adapted to film. The draining monotony of tour life is captured in repetitive beats—flights and cabs, readings done on autopilot, brief encounters with abrasive strangers, quick calls home from beige hotel rooms—but the sequence itself never becomes monotonous. In each new city, we’re given more of Olive’s lecture on the history of pandemics, a rumination on the meaning we derive from them and why every age believes the world is ending, and as the tour progresses, so too does news of a virus supposedly contained in Australia.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

It’s an engrossing expression of exhaustion, loneliness, and mounting dread made surreal by its nakedness—it never shies from reminding the reader that it’s written by a writer who imagined a pandemic then witnessed a real one. Not surprisingly, Olive is the most fully realized character in the book.

Unfortunately, there’s no one else even close. The back half of the novel weaves the mystery’s strands together, but as clean as the work is, and as impressed as I am by the high-concept execution, the attempted poignancy feels perfunctory due to the lack of character development and some anemic dialogue. The protagonist’s decisions, including a change of heart that puts the entire drama into motion, have little resonance and feel more instrumented by the plot’s next beat than anything that’s been meaningfully developed.

The Violin Conspiracy is a whodunit, coming-of-age story, with a blunt critique of this violently racist country and the rich, white, Eurocentric milieu of classical music. I didn’t read the back matter before diving in, and the opening was fresher for it.

The story begins with the theft of a young Black superstar violinist’s $10 million Stradivarius. This is just a month before said superstar, Ray, is to compete in the prestigious Tchaikovsky Competition, held in Moscow. Suspects are mentioned early and often—the Marks family, Ray’s own family—but the causes of suspicion are teased out over the course of the book’s first half, which jumps back in time to cover: the origin of the violin—a “gift” to Ray’s great-great-grandfather from his former enslaver; the Marks’ claim to it—they’re descendants of the enslaver; and Ray’s family’s potential motive—they’re mostly working class and think him selfish for playing the violin instead of selling it and sharing the money.

The mystery, ultimately, is a framing device for the bildungsroman and social critique, which is a good thing, because the mystery is thin. The “who” is easy to guess, but more critically, the cast of supporting characters is flat. The characters aren’t developed enough to be intriguing or truly duplicitous—we must sense enough of a mind at work to be deceived.

My favorite scene is one of the rare instances where that pattern seems to break.

Most of the supporting characters in The Violin Conspiracy exist solely to be supportive or unsupportive. The author’s note reveals that much of the story is drawn from his own life—the racist incidents, the supportive teacher and angelic grandmother, even the theft of his expensive violin—and was written to convey that surviving in America as a young Black man requires support. Thus, it makes sense that support is a central theme, but it impoverishes the story and drama to reduce supporting characters to that single end, to have them appear, play that beat—pep talk or takedown—and disappear.

My favorite scene is one of the rare instances where that pattern seems to break. Ray’s mother attends his first concert performance with his Stradivarius and afterwards appears backstage. Up to this point, she’s been entirely hostile to Ray’s musical aspirations and is presented as callous and self- (or money-) centered. In this scene, however, she brings a bouquet, they have a pointed but playful banter about sharing the $10 million fiddle—is this a new tactic?—and Ray throws himself into her arms and she stiffly reciprocates. The scene is brief and perhaps I’m projecting, but the ambiguity around the shift in her tone and the slight suggestion of her discomfort in the white-dominated space—which is supported by an earlier mention of her not wanting to sit in an “alien concert hall” with “soccer moms” wondering if she’s lost—deepens her as a character. The moment doesn’t change anything; in fact, it’s surprising how little Ray’s mother figures in the second half, but the scene lingers.

The concert performance scenes largely work—it’s hard not to cheer Ray on as he puts racist concertmasters in their place by switching tempos on them (“Charity work’s a bitch, huh? How’s that for a PR stunt?”)—and the Moscow scenes generate a flash of complex feeling. Ray arrives at the Tchaikovsky building in awe but notices its real-life grubbiness. He meets others his age and recognizes them as his “tribe”—those who live classical music and truly understand the loss of a Stradivarius—but he also knows they’ll always treat him differently because of his Blackness. It’s a dream bittersweetly realized.

But this acute and affecting ambivalence is soon jettisoned for something more pat. This is in line with the novel’s preference for clarity, which often results in emotional beats that are telegraphed and prose leaning toward cliché with a tendency to overexplain what was obvious to witness. Unless a writer can push deeper with lyricism, exposition robs us of our experience of the text—which is, I believe, what moves or unsettles us.

For a reader hoping to tussle alongside the text, there’s nothing more deflating than being overexplained to. Sea’s faults swing somewhat in the other direction in that there’s sometimes not enough on the page. For a book espousing that, even in the face of death and existential loneliness, tranquility is possible by slowing down, by being still, it has no patience for long scenes and sacrifices character building for plot and pace. But at its most meta, Sea puts something in play that begins to grapple with the arresting shock of the last few years. The sequence is short, and has too many answers, but the glimpse is real enough, a reason to read.

Advancing:

Sea of Tranquility

Match Commentary

with Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile: First of all, a shoutout for the judge’s shoutout to 2012 Rooster finalist Open City. We were all babies then, John.

I suppose we usually judge characters in novels on a scale of believability. The more detailed and real they seem, the more the world of the book comes alive in our imagination. And that’s a fine way to think about most novels. But character is also a tool of the writer, one that can be employed in many ways.

Largely because of the recent Academy Awards, I’ve been thinking a lot about The Banshees of Inisherin. In that movie, Colm, the character played by Brendan Gleeson, introduces an unresolvable conflict into his longtime friendship with Pádraic (Colin Farrell). Colm’s behavior is barely explained and doesn’t make much literal sense because his actions are a metaphor for global conflict—civil wars, religious hostilities, etc.—and predictably his “war logic” leads to escalation, severe wounds, collateral damage, and civilian casualties. Pádraic, however, responds the way an individual human might (as opposed to a nation state or a persecuted group), which is the source of dark humor in the film.

Mandel has the toolbox open in Sea of Tranquility. Her characters are like reverse Pinocchios—they thought they were real people but are starting to suspect that they might have been puppets all along. As the judge notes, the reader recognizes a superficiality in them that they don’t see in themselves. Sea of Tranquility’s characters are doing a lot of meta-work in this novel, but it’s not necessarily the kind of job we’re used to fictional characters doing.

John Warner: That word “believability” is always tricky, right? One of the most common comments you’ll hear in a writing workshop is about a character’s believability, or the reader not “believing” in a character’s particular action.

This may or may not have anything to do with the character as drawn in the story, so I’ve often found myself part of ultimately unproductive conversations in these workshop situations as we talk about what kind of character would such an action be believable from, or what kind of action would be believable from a particular character.

What I think these conversations tend to miss is the incredible interrelated organic system that is a novel-length work. I don’t want to push on this too hard, but a character’s action might be viewed as not believable not because in a vacuum the action is not believable, but simply because the language used to bring it to life is not working as desired.

Or it there may be something fundamentally off-putting about the underlying story universe, which is my rub with Banshees, and even more strongly with director Martin McDonagh’s previous feature, Three Billboards in Ebbing, Missouri, which is absolutely one of the most, if not the most infuriating movie I’ve ever seen because there was not a single note in that movie that was “believable.”

I know some people who find Three Billboards to be deeply compelling, emotionally moving, and I judge them for it—you bet I do—but our Commentariat gets that as they hash out each day’s results in a way that is respectful, but also quite firm about what individuals see as the relative merits of the books.

In many ways, the judge finds The Violin Conspiracy the more believable of the two books, calling the critique of white supremacy culture “blunt” but also not suggesting it is incorrect.

It fell short because of the “experience of the text.” I like that. It’s ultimately what it all comes down to, yes?

Kevin: Sea of Tranquility, like Banshees, requires a certain buy-in from the reader. If I had read it only on a surface level, as a dystopian sci-fi novel about time travel, I don’t think I would have thought it was a very good book. But the meta-business Sea of Tranquility is engaged in happens to be on a subject that interests me very much, and I thought it integrated that with a facsimile of a sci-fi novel in a way that was brilliant.

My wife (whom you know, and who is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met) had almost no patience for Banshees. At the points where she was willing to engage with it, she just didn’t believe it. And that’s perfectly legitimate. She “got” the metaphor, but she wasn’t interested in it enough to disregard all the stuff that seemed ridiculous to her. (Frankly I’m amazed at the number of people who profess to love Banshees, but who also seem to accept that it is just a movie about friendship.)

John: Banshees is set against a stunning backdrop, the performers are all top-notch (as is also true in Three Billboards), but that doesn’t stop the film from being top-to-bottom bullshit. That said, I did laugh a couple of times, but the same as your very perceptive partner, I didn’t believe it for a second. It was manipulative in the extreme, and not in a good way.

I better stop before I get angry all over again.

Kevin: The judge seems to have been bothered by some of the superficiality in Sea of Tranquility, but thought its meta-commentary was more interesting than the more traditional social commentary in The Violin Conspiracy. As you point out, even thin or ridiculous characters can be believable in context. Sea of Tranquility advances.

A quick check of the Zombie voting reveals that The Violin Conspiracy does not quite have the Strads to make it into the top two. If the Zombie Round were held today, Babel and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow would be our lit-crit clickers.

Today’s mascot

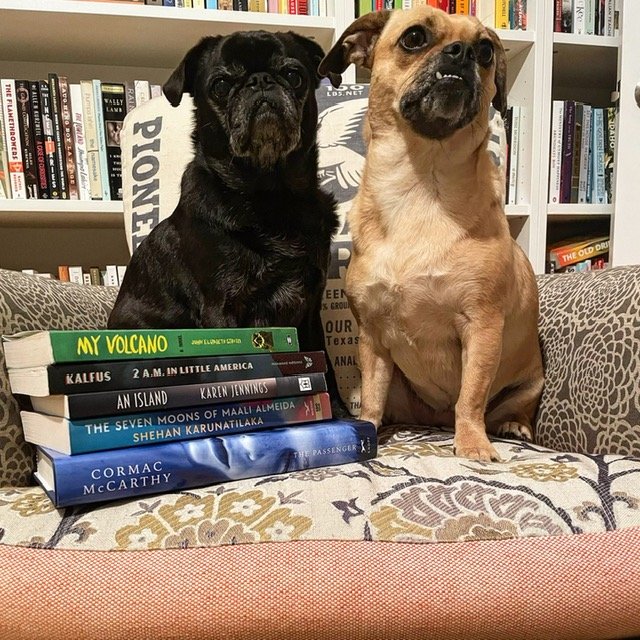

Today’s mascots are brought to us by JoDee: dogs Maizey (pug) and Shiloh (pug mix). The yin and yang of book-loving pugs, Maizey Blue prefers her novels filled with animal adventures, while Shiloh is attracted to timeless tales of pirates and lost treasure (arrr!). But most often both can be found snuggling with the readers in the house, Maizey on lookout atop the blanket with Shiloh spelunking beneath, until both settle in for hours-long naps, snoring and sleep-running to the best of the Tournament of Books.

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.