Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance v. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 22 • QUARTERFINALS

Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance

v. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow

Judged by Calvin Kasulke

Calvin Kasulke (he/him) is the author of the novel Several People Are Typing. His work has appeared in VICE, MEL Magazine, DC Comics, and elsewhere. He lives in Queens with his dog Jeff. Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / neutralspaces.co/calvin_kasulke

It’s an audacious thing to use a famous line from Shakespeare as the title of a novel. I admire this kind of called shot; as a reader, my attitude toward any new book is “fuck me up,” and it’s a safe bet that someone willing to evoke comparisons to Macbeth from jump is promising to do just that. Spoilers to follow, obviously.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is grandiose in its references and ambitious in its scope—two points already in its favor. Its narrative spans the history of video games from arcade cabinets and the original Super Mario Bros. through the not-quite-present-day via a story of a creative partnership—which I’m struggling to call anything but “star-crossed”—between Sam Mazer (né Masur) and Sadie Green. Sam and Sadie became best friends through a shared tweenage love of video games, but an early betrayal spikes their friendship for half a decade and sets the pattern for their connection; the novel follows the tidal pattern of Sam and Sadie’s coming together and breaking apart through a series of nearly unbroken joint professional successes and a spate of harrowing personal catastrophes.

The pair reconnect in college, this time not just as gamers but as game designers. Their first collaboration, Ichigo, is a hit. This allows them to cofound their own studio, Unfair Games, whose struggles and successes undergird much of the novel’s plot from there on out. These early sections illustrating Sam and Sadie’s creative connection are electric, but I found myself missing this initial spark as the two spend much of the book openly fighting, secretly fighting, or not speaking at all. That Sam and Sadie also bemoan this at various points throughout the book makes it clear the reader is meant to feel the loss as acutely as they do, but it doesn’t do much toward recapturing the energy of those chapters.

I’m struggling to quickly describe either of them in the same way I do when asked to briefly characterize a close friend. I have too much information to be pithy.

Neither Ichigo or Unfair would be possible without the administrative skills of Sam’s college roommate and Sadie’s eventual lover, Marx Watanabe, a character so refreshingly warm and non-neurotic it was obvious he was never going to make it out alive. Nevertheless, when the time finally came for Marx to die I had to put the book down and pace around the coffee table for a few minutes before I could bring myself to read the chapter—subsequently my favorite in the book, which starts with a brutal shift from the novel’s close third POV into the second person:

You have had many lives… You are American, Japanese, Korean, and by being all of those things, you are not truly any of those things. You consider yourself a citizen of the world.

You are currently a citizen of the hospital. A machine is breathing for you. Regularly spaced chirps indicate that you are still alive.

This section is one of the biggest formal swings in the book and, for me, the most impactful—I liked Marx! And though we spend most of the book alternating between the perspectives of Sam and Sadie, I somehow came out of it feeling they were less realized than some of their supporting cast. Tomorrow comes in at just short of 400 pages, which is a lot of time to spend with the thoughts of (predominantly) two characters, and I’m struggling to quickly describe either of them in the same way I do when asked to briefly characterize a close friend. I have too much information to be pithy.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

The constraints of both this judgment and linear time prevent me from fully digging into the story’s structure—non-linear chronology, multiple POV characters, some really effective sections told from characters’ perspectives while immersed in the video games themselves—or its many, many themes and motifs; there’s a lot going on here, and it follows that some parts landed better for me than others. That’s the nature of sprawling, ambitious books. Some unevenness is to be expected.

Going from TATAT right into Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance felt like looking through a telescope one minute and then a microscope the next: Everything you’re seeing is wondrous, but there’s a significant difference in scale. Notes maintains a laser focus on how grief unravels the lives of its small cast of characters while life itself cruelly plods ahead, but I felt perversely reassured by this limited (if occasionally devastating) scope.

Candidly, I didn’t expect to remain engaged in a narrative exclusively dedicated to tracing the fallout from a single teenager’s death, but Notes kept me engrossed long after the grieving process had become monotonous to the characters themselves. Much of the credit for that is owed to narrator Sally, who deftly, minutely observes her surroundings and whose perspective is a pleasure to inhabit, wracked as it is by grief, the typical trials of an American adolescents in the late ’90s and early aughts, and her singular relationship with deuteragonist Billy.

Sally tells the story from the vantage of her late 20s, but she’s not narrating to some general audience. As the title suggests, the “you” she addresses throughout is Kathy, her late older sister. Kathy is killed in a car accident that both Sally and Kathy’s boyfriend Billy, the car’s driver, survive. Billy was an object of fascination for Kathy and Sally as preteens in suburban Connecticut, and transforms into a point of contention as varsity basketball star Billy becomes Kathy’s high school boyfriend—which further diminishes the time popular, talented Kathy spends with her younger sister.

Maybe this is all rationalization to support a more undefinable standard.

In their grief after Kathy’s death, Sally and Billy forge a connection that alternately buoys and haunts the narrator through the rest of her secondary school career and into her early adulthood. Throughout the text, Sally frequently refers to Billy as “your boyfriend” (emphasis mine). As if it wasn’t enough to position you, the reader, as merely the dead sister whose tragic passing is the catalyst for the entire novel, and now you’re feeling kind of jealous sympathy toward your alive sister and the beautiful but grief-gnarled intimacy she’s cultivating with your man? Those kinds of subtle emotional wrinkles are what made Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance such a standout for me.

In its relentless focus on one family’s grief over the loss of a child, Notes is no less ambitious than its opponent in this round; what puts it over the top for me was the precision of its execution. Every sentence felt polished to a high shine, allowing the story to spill toward its inevitable (if still ambiguous) conclusion.

Maybe this is all rationalization to support a more undefinable standard. Past a certain point of basic literary competency, my enjoyment of a book is mostly inflected by what the story asks of me as a reader. There are plenty of ways in which novel can call on you to be an active participant: requiring your puzzle-solving skills in unspooling a mystery, demanding your culpability as you follow a character unwittingly engineering their own ultimate downfall, engaging you to suss out when or how or whether a narrator is being unreliable, and so on.

I tend to fall for stories that invite a relationship with the text that I haven’t yet experienced, or those that inflict a familiar kind of participation on me in novel ways. Here, again, Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance edges out Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow in casting the reader as the departed sister around whom the story orbits. I haven’t been dead before. With apologies to Shakespeare, I want a book to claim its figurative pound of flesh from me; here’s how it shook out on the scales.

Advancing:

Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance

Match Commentary

with Rosecrans Baldwin, Meave Gallagher, and Alana Mohamed

Rosecrans Baldwin: Is this the first time we’ve got a judge whose novel was in the Tournament only the previous year? (Of all people, I should know?)

Andrew Womack: John Green. It was John Green.

Rosecrans: Alana and Meave, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is one of this year’s mega books, considering ubiquity and sales, but it didn’t quite work as well for the judge as Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance, in terms of what it gave him in precision and asked of him regarding participation. Personally, I would’ve voted the same—I found Tomorrow zippy but too didactic, whereas Notes slowly grew fangs. I don’t know if you’ve read both books, but what do you think?

Meave Gallagher: First, my compliments to Judge Kasulke for Several People Are Typing, one of my favorite books of 2021. What a gem.

Rosecrans: Truly.

Meave: To extend our judge’s telescope analogy, as the scope of Tomorrow widened I felt less connected to the characters. I also didn’t love Tom Bissell’s New York Times review—that lede! Cite a source, man!—but, like Judge Kasulke, I felt the book’s structure undermined the effect of the sudden violence. And one chapter can’t carry the whole novel.

Alana Mohamed: Wow, that lede is not great. I am embarrassed to admit I did not finish the much buzzed-about Tomorrow, but that excerpt from Marx’s chapter makes me wish I had.

Meave: I didn’t read Notes and I feel no need to, if that helps.

Alana: I’m a sucker for second-person narration, a technique that has popped up in several other matches. Its use seems especially fitting in a book about video games, like part of the thrill of playing is assuming another identity.

Rosecrans: Right, and in today’s match it’s a shared device, and for today’s judge at least, a persuasive one in both cases.

Meave: Interesting point about the prevalence of the second person this year. Not a voice I’m often drawn to; it tends to pull me out of the book rather than further in.

I’m told that—much like reading—it’s way more fun to play a game as/with a main character who appeals to you, which makes sense; video game scholars love to talk about games as text (to the point of sounding defensive, which, just be cool, we’re taking you seriously).

What’s been your experience with video games? We were a “video games are a mindless waste of time” household, which has been hard to shake. But my husband and stepson love them, so I’ve learned to respect others’ enjoyment of them. Still, there are plenty of intersectional critiques of games and the gaming industry that are overlooked for the old “violent games = violent behavior” sawhorse, and those deserve more attention.

Rosecrans: Nintendo when I was a child, shooters when I was young adult, and now I do the crossword at lunch, does that count?

Alana Mohamed: I’ve never been a big gamer. But Meave, aren’t the issues you’re pointing out prevalent in all entertainment industries? I get that these issues do inform Sam and Sadie’s relationship and professional endeavors, but it seems like it wasn’t hitting quite the right notes.

Meave: Another subgenre of “marginalized people disabused of their idealism by the man,” hooray.

Alana: Did we both walk away from Tomorrow wanting more than it could give? I put it down because I kept imagining it being adapted into some quirky early-aughts movie. Meave, I wonder if that stems from what you said about Tomorrow not having much to say that you didn’t already know. What did you feel it was trying to say? On its face, Notes doesn’t necessarily tell us anything new either. Death is sad and weird and will fuck everything up, though the book still illustrates that beautifully.

Meave: Paramount snapped up Tomorrow’s film rights, so get ready for that very adaptation. Mostly what I got from Tomorrow is “hurt people hurt people,” and, yes. Now do something interesting with it.

Rosecrans: The judge favors “subtle emotional wrinkles” in fiction. I like that phrase and it’s something I treasure too. Here’s a question: Over the years, in judgments and among the Commentariat, a lot of ToB discussion is around what turns people on when they read novels and stories. So, what are a couple things that turn you off?

Alana: Funnily enough, the main thing that turns me off is a story full of polished sentences. This is something Judge Kasulke prizes in Notes and I can see why. Those subtle emotional wrinkles demand them! But to me, these sentences always call to mind the work that went into them, which ends up being a distraction. Perhaps this just reveals my own aversion to work.

Rosecrans: Lol.

Meave: Alana, after everything you’ve been saying about working, no one’s going to believe you’re averse to it. Some books are just show-offy. Still, it’s interesting that Judge Kasulke chose Notes because it demanded more from him as a reader. Tomorrow told me little I didn’t already know, and not much stuck. I want new perspectives, not an ex’s origin story. (Forever scarred from having lived in San Francisco at the birth of web 2.0).

Alana: I studied creative writing in college (lol) and suffered through many stories about misanthropic suburban youth, so I’d say that kind of thing always takes me a second to get into. This was another reason I didn’t expect to like Notes as much as I did.

Meave: I won’t defend disaffected suburban youth; I was one and I was insufferable. Maybe we should redesign suburbs so they aren’t soul-deadening?

Alana: Revitalize the suburbs, revitalize fiction!

Meave: Fifteen-minute cities and repugnant autofiction, let’s go! To pick a couple of nits, when an author is obviously trying to hit their word count by avoiding contractions, the characters just sound like data (not lore!). Speaking of, I do not understand what the British have been doing with commas. Essentially, when the rhythm is off, it wrecks my flow (that’s for the Stafford Beerheads).

Alana: Flow is everything! Though I suppose each technique has its uses and time to shine. Maybe next year’s ToB will be full of rhythmless books about grammatically deficient robots.

Meave: Cue panicking about AI lit in three, two—

Rosecrans: And that’s today’s match! But here’s a quick update from Kevin on where things stand in the Zombie poll.

Kevin Guilfoile: Thanks! Yeah, taking a glimpse at the Zombie results we find that Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow has crept into the sprint. If the Zombie Round were held today, Babel and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow would be trying to kill our bibliographical Brendan Fraser.

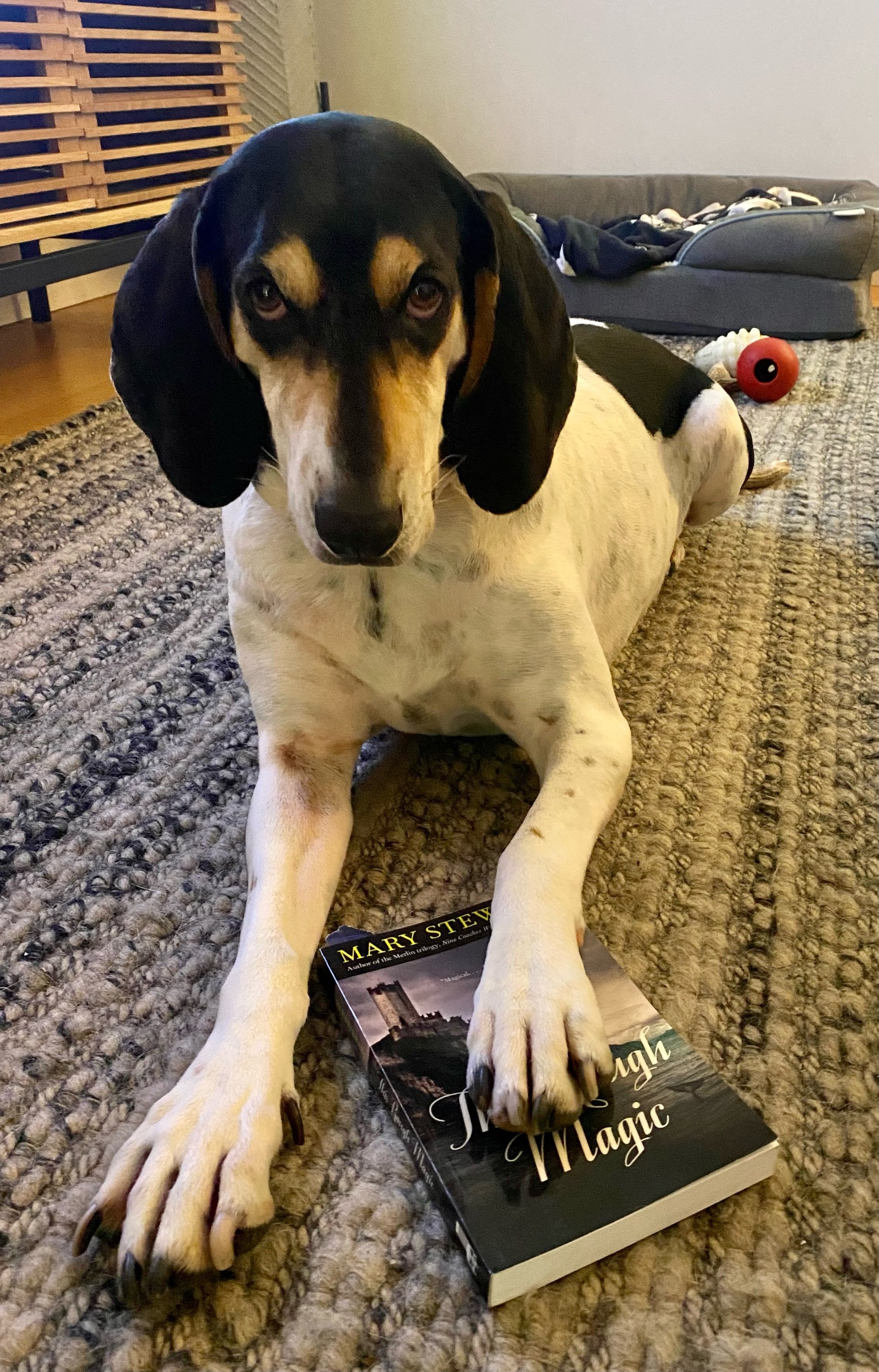

Today’s mascot

ToB fan Kathryn brings us today’s mascot, the delightful Maggie Jo! Maggie Jo is a rescued Treeing Walker Hound. She lives with her people in Los Angeles and has three major purposes in life: 1) to convince you that you forgot to feed her; 2) to subdue any wild animal entering her space (animals subdued include opossum, rat, and [almost] a raccoon); and 3) to get the best/most space on the couch (she is champion-level at this). She also was Kathryn’s nurse after a serious cross-country skiing accident—remarkably sensitive and sweet. Also, she has the softest ears possible. Welcome, Maggie Jo!

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.