The Librarianist v. What You Are Looking for Is in the Library

The 2024 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 15 • OPENING ROUND

The Librarianist

v. What You Are Looking for Is in the Library

Judged by Steffan Triplett

Steffan Triplett (he/him) is the author of Bad Forecast, forthcoming on Essay Press, and the chapbook Constraints on DIAGRAM/New Michigan Press. Steffan teaches at the University of Pittsburgh where he is the managing director of the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics (CAAPP). He is an Essay Editor at The Offing and has received fellowships from Cave Canem, Callaloo, Outpost, Lambda Literary, and the National Book Critics Circle. Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / steffantriplett.wordpress.com

What You Are Looking for Is in the Library drizzled the days I read it in a sweet glaze. Amid pre-holiday, masked travel and a mild case of stress-induced shingles, the last thing I wanted to do was read anything strenuous. The world outside was cold and burning. The news, as it does, droned on evasive and ignorant of the lives being stolen through crisis and genocide. Distinctively, like the cookies of Ms. Komachi’s recycled tin at the book’s center, each of the five stories in the novel was concocted as a sweet treat, a confection in a box.

In the world of What You Are Looking for Is in the Library, all its main characters are on the precipice of change: like a woman (Natsumi, 40, former magazine editor) with a hidden desire to become a book publisher, or a man (Ryo, 35, accounts department of a furniture manufacturer) who daydreams of opening an antique shop but is afraid to pull the trigger. Each is at a crossroads in their life; each of them is (literally) introduced to us, defined by their current job, and each finds their way to the library whilst utilizing the resources of a local community center.

It’s honest about how one engages with literature—there can be a selfishness to it.

This sugary vision of the Hatori Community House reaches its heights in librarian Ms. Kamachi, who is both very competent and very cartoonish—she is even described as looking like Disney’s Baymax (a moment I take issue with; each character comments on and is stunned by her size). Each of the five stories allows for one of five protagonists to run with one of her (seemingly off-topic) book suggestions and find new meaning from it. When she’s confronted about her strategies and intentions, she downplays her meddling in jolting these characters into action: “You may say that it was the book, but it’s how you read a book that is most valuable, rather than any power it might have itself” she tells one of the patrons.

It’s a bit saccharine, but I also think it’s honest about how one engages with literature—there can be a selfishness to it. It’s not just about the book, it’s about you as a reader, what’s going on in your life, what sticks to you. I wanted more moments that evoked this prickliness. But mostly in the stories of What You Are Looking for Is in the Library, you can anticipate what you’re gonna get. Nevertheless, it's pleasant and enjoyable.

Patrick deWitt’s TheLibrarianist was a stickier read. I read it a handful of days later—my shingles were dying down as the news only got worse. I yearned for something that offered something to the mix of emotions I was feeling, reflective of my life on this turning globe, a new year on the horizon. I found it surprisingly easy to get wrapped up in one person’s life—though I initially kept protagonist Bob Comet, a 71-year-old retired librarian, at arm’s length. I didn’t know what secrets he might reveal to me nor what type of story to anticipate.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

While out on a walk, Bob Comet encounters a disoriented woman at a 7-Eleven who has trailed off from the local senior center. After returning the mysterious woman to the home, and being drawn in by its opportunity for company and purpose, Bob decides to spend his days volunteering there. The more time he spends attempting to build connections with the residents, the more he learns about their lives and desires, as well as his. What I noted throughout my read of the book was how often Bob thought about feelings of content or discontent, particularly with the smallness of his life. Upon revealing a family secret to Bob, his mother tells him, “I wanted you to understand that the story of your father and me is a small story, but that doesn’t mean it’s an unhappy one.” I appreciated this insistence, how it makes peace out of one’s decision and its consequences. It seemed antithetical to the job-speak I found myself somewhat allergic to in What You Are Looking for Is in the Library.

What was most difficult about this novel was where it decided to meet and leave the reader. The structure was confounding to me at first. While the present of The Librarianist takes place in Bob’s 71st year, we then flash back to his childhood, tracking him from his first experiences in a library, then spending the most time when he was in his early twenties working as a librarian. Here he would meet both his best friend Ethan and Bob’s future wife Connie, who we know will leave him. I loved this section, loved the shapes of Bob that were beginning to form. It was a surprise then, that the next section doesn’t go forward in time to resolve what’s been set up, but backward, instead following adolescent Bob as he ran away from home at age 11 for two weeks in 1945, traveling away from Portland to a seaside hotel.

Perhaps the next year in one’s life, or in one’s book of their life, could take up triple the amount of space of all that precedes it.

Bob’s adventures to and at the Hotel Elba are a strange detour—a kookiness and tone that felt to me, at that moment, proximate to a Lemony Snicket novel. I was frustrated at first by this shift in tone, but then compelled into curiosity. It departed so much from what had felt mostly before a grounded facsimile of reality. I perhaps had more fun sitting with the questions it stirred up in me than the actual plot that transpired at the hotel. (Is this a made-up, imagined story from an adolescent yearning for escape? What makes up a person? Their reality, their memory, or their daydreams?) But more than anything, I was surprised. The novel ends on a strange scene, where we see a new side and demeanor to our protagonist, and I found myself moved. Perhaps the best is yet to come. Perhaps the next year in one’s life, or in one’s book of their life, could take up triple the amount of space of all that precedes it.

One moment I keep returning to as I worked to decide which book to advance was in The Librarianist when a librarian tells Bob, “All my life, all I ever wanted was to be alone in a room filled with books. But then something awful happened, Bob, which was that they gave it to me.” I felt surprised here: I felt attacked. Both novels involve the idea of public libraries, which frighteningly seem increasingly endangered. I believe in the power of books and literature. But this quote had me consider how there’s both great power in books but also a danger in their solitude if one isn’t using them in tandem with the world, off the page around them.

I’m advancing The Librarianist, partially for its unpredictability, but also for where it has my mind running, how it has me looking forward to not what needs to change in my life, or what job is next, but rather how I should be attentive to the ride, to both books and the not-books happening around me.

Advancing:

The Librarianist

Match Commentary

with Meave Gallagher and Alana Mohamed

Meave Gallagher: Hi, fellow librarian! Ready to talk libraries in fiction?

Something that struck me about Judge Triplett’s decision was his reaction to a conversation in The Librarianist: “‘All my life, all I ever wanted was to be alone in a room filled with books. But then something awful happened, Bob, which was that they gave it to me.’ …This quote had me consider how there’s both great power in books but also a danger in their solitude if one isn’t using them in tandem with the world.” I wondered how much the judge, before reading The Librarianist, had thought about libraries as places other than book depositories—which is no knock on him! But do I ever wish we could put to bed that idea of “libraries are for quiet reading.” Treating them as places to silently worship the written word, with an older lady grumping about shushing everyone, is so dated (and sexist!), it’s embarrassing.

Alana Mohamed: I got the impression that the quote from The Librarianist forced Judge Triplett to reckon with the idea that loving books is a virtue in itself as a comment on Bob’s journey specifically.

Meave: Totally! Oh, totally. And not to speak for our esteemed judge, but it seemed like he took at least some issue with the sort of stereotypes of libraries and librarians in The Librarianist and What You Are Looking for Is in the Library. Alana, you work in a dynamic metropolitan library. Did either of these depictions of libraries/librarians seem—how to put it—weird to you?

Alana: Both have romantic ideas about libraries, which I don’t think is weird at all. So many people do, even people who regularly use them. What You Are Looking for Is in the Library seemed to conceive of the library as a magical space for community, while The Librarianist explored the fetishization of the lonely booklover.

Meave: “The fetishization of the lonely booklover”—ugh. I’m so grateful to have grown out of that “my personality is Reader of Literature” thing.

Alana: It was nice to see The Librarianist slowly undo that stereotype.

Meave: It was a relief.

Alana: Both books seem to position the librarian as lonely, too, which we know is true in reality: Librarians are expected to perform many different functions with little support, which can be isolating. To that point, Ms. Komachi in What You Are Looking for Is in the Library seems to be less a person, more a genie, in function and appearance.

Meave: I’m also glad the judge pointed out the way Aoyama’s characters described Ms. Komachi. The whole “joke” of Surprise, the librarian is fat and scary! just seemed cruel, and it soured me on the book, as did the relentless “job-speak” that put off Judge Triplett as well.

Alana: I would characterize Ms. Komachi as a “genie” because her size seemed to indicate something larger than life and possibly supernatural, the magical fat character who exists solely to help others.

Meave: Seems like a reasonable guess.

Alana: I had a lot more tolerance for the job-speak, but I did find it funny that a book so consumed by the question of careers received the more saccharine treatment, while the book about volunteering is “stickier.”

Meave: Haha, right. I’m not sure whether the judge would agree, but I had trouble taking What You Are Looking for Is in the Library as a fully realized text so much as a career advice book that someone’s well-meaning parent would suggest to them after they got laid off.

This makes me think about Judge Triplett’s reason for giving the win to The Librarianist: “...[I]t has me looking forward to not what needs to change in my life, or what job is next, but rather how I should be attentive to the ride, to both books and the not-books happening around me.” My mother-in-law is very much of the “aspire to a good job, and then you can enjoy your retirement” school. But my husband doesn’t want to wait until “retirement” (lmao) to build a life external to work. And he’s staunchly opposed to tying one’s identity to one’s job.

Alana: Yeah, it may speak to where we are economically that everyone’s feeling very allergic to job-speak. For what it’s worth, I think Ms. Komachi saying, “[I]t’s how you read a book that is most valuable, rather than any power it might have itself.” That seems like a similar directive to enjoy the ride, but the focus on career does undercut this message.

Meave: I wonder if that’s not a cultural difference we’re missing: not being Japanese. I got the impression that Judge Triplett was overall underwhelmed by both novels. What You Are Looking for Is in the Library is “pleasant and enjoyable.” The Librarianist dwells on Bob’s “feelings of content or discontent, particularly with the smallness of his life.” I would add the anachronistic portrayals of libraries as “small quiet places for books” as another detractor. Today’s libraries are so dynamic, but neither of these books portray them that way.

Alana: I ended up viewing the library as more metaphor than anything in these books, but you’re right that they don’t necessarily showcase all they have to offer. I do understand why so much of Judge Triplett’s decision rested on the stranger elements of The Librarianist. It seems like What You Are Looking for Is in the Library had some elements of a fairytale, in that there’s an otherworldly character dabbling in the lives of lost mortals, but that also means the stories are formulaic and teach a clear lesson.

Meave: I’m glad our judge appreciated both books’ focus on the possibility of change. To me, that was their most redeeming shared quality. Though I agree that watching Bob brave the risk of becoming someone new was preferable to the tale of an unemployed 30-year-old falling into a part-time job and flirting with a teenager.

Alana: Right, it’s more engaging when you get to ride along with someone. I kind of liked that Judge Triplett said he felt “attacked” at one point in The Librarianist, that there was something that challenged him.

Meave: Please see my comments above on “the fetishization of the lonely book lover.”

Before we wrap up for today, a tip for US/Canadian readers: The Japan Foundation offers free digital memberships, through which you can access lots of Japanese works (in the original and in translation) that most libraries here may not carry. Check them out! Meanwhile, Alana and I will reconvene on Monday for the final match of the opening round, which sees Judge Taija Isen deciding between Monstrilio’s horror-grief and American Mermaid’s hazy meta-narratives.

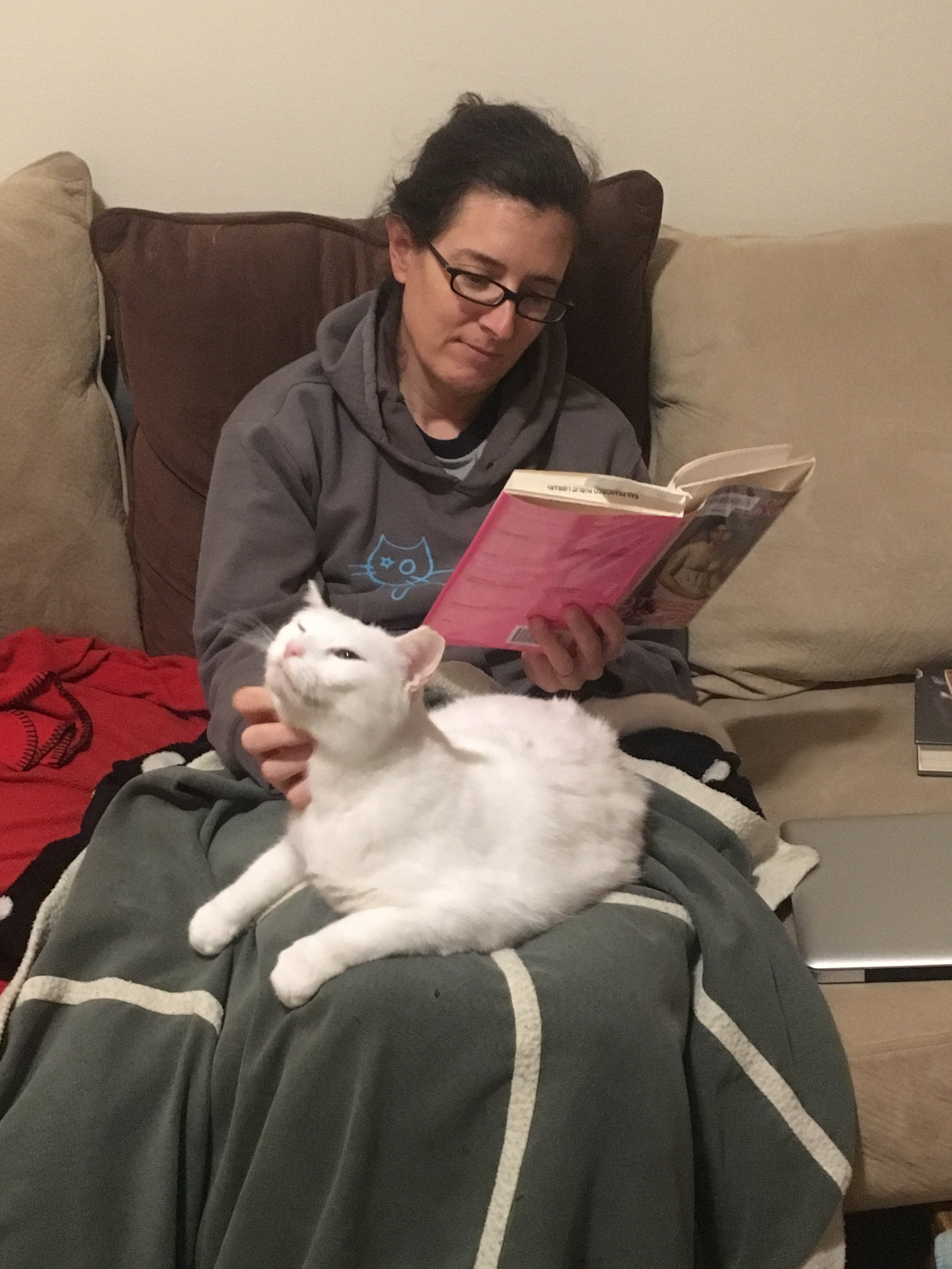

Today’s mascot

Please welcome today’s mascot, Esamarelda Doolittle, aka Ezra but mostly aka Beans, domestic shorthair Brooklyn street cat, 2006–Jan. 17, 2024.

Nominated by Audra, who tell us, “Beans spent the first several years of her life with us refusing to be touched and then shifted to living on Loren’s lap pretty much full time where she would absorb via osmosis whatever was being read.

“While reading on her own, Beans enjoyed books about world domination and get-rich-quick schemes. We do not know how she got over 1,000 Facebook fans.”

We do. Thank you for sharing, Audra and Loren.