The Violin Conspiracy v. Manhunt

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 16 • OPENING ROUND

The Violin Conspiracy

v. Manhunt

Judged by Aminah Mae Safi

Aminah Mae Safi (she/her) is the award-winning author of four novels, including Tell Me How You Really Feel and Travelers Along the Way: a Robin Hood Remix. She’s an erstwhile art historian, a fan of Cholula on popcorn, and an un-ironic lover of the Fast and the Furious franchise. Her writing has been featured on Bustle and Salon and her award-winning short stories can be found in Fresh Ink and the forthcoming Freshman Orientation (2023) and Out of Our League (2024). Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / aminahmae.com

What no one tells you about judging books is that any measure of taste relies solely on the whims of a judge.

That’s me. My whims. My tastes. My literary inclinations.

We want to pretend like there is some objectivity in this game, but there isn’t. I tell you this from the start: I love a literary mystery. I tell you this from the start: I struggle with body horror. I didn’t always. But having undergone a double mastectomy 18 months ago changes a body’s perspective on the whole thing.

My confessions do not make the following any more objective.

Both Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin and The Violin Conspiracy by Brendan Slocumb deal with the ways in which identity becomes intertwined with structural inequalities. In Manhunt, the metaphor is rooted in the barriers and violence placed before transgender women to prevent their very existence.

The book is a brutal, riveting fight through those barriers. A horrific battle royale through the systemic oppression of trans women in specific and queer bodies at large.

Then there is The Violin Conspiracy, which deals with the uphill battle that Black musicians face in the classical world. I couldn’t help but think of Nina Simone, a classically trained pianist, and her unpaved road to Carnegie Hall. I kept thinking about unraveling mystery of The Red Violin and who gets to inherit a lineage and a pedigree and who does not.

The Violin Conspiracy is one driven by heartache and longing. To love a thing that doesn’t always love you back. To refuse to give it up, regardless.

Perhaps this reveals more about me than the books, but I have such admiration for the vulnerability displayed on the pages of both of these two incredibly distinct works. To tell the truth involves showing yourself, whether you realize it or not.

Great horror is rooted in the body. It makes you feel.

And contrary to popular maxims, fortune does not always favor the bold.

Ah, but I do.

In Manhunt, the world is overrun by feral men. A plague triggered by testosterone-fueled bodies might be seen as reductive and biologically deterministic by some readers. Yet, in using this as the feral-man-plague trigger, Felker-Martin wields a metaphor that is simultaneously a subtle knife and a cosmic warhammer.

We fall down the rabbit hole of the loopholes of every anti-trans belief. It is a gruesome Wonderland, make no mistake about it. But it allows for those arguments to collapse in on themselves when made into a textural reality.

Manhunt is a staccato, frenetic book. A frenzy of a book. Reading it was like listening to The Rite of Spring for the first time. Told from multiple points of view, we largely follow Beth, Fran, and Robbie as they try to survive a world where men have gone feral. Where a queer body is inherently vulnerable to the beliefs of the society around them. A world where few are safe and cults aren’t just taking hold: They’re thriving.

Great horror is rooted in the body. It makes you feel. Manhunt exemplifies that feral, bodily thing that is horror. The thrill of fear and of imagining what it is to have your body at the center of such a grim reality.

This is where I come back to my own tastes. I do not find catharsis in body horror. For that is the aim of any real horror story. To root that dread and that nausea and that pain in the body so the audience might find relief on the other side. To feel and then release that horror. To decide that even in an environment of such deep feeling, fear has no power over you. That you are bigger than the worst of your fears.

I say this because if you want a book that is rooted in the body, that is unapologetically queer, in a world where violence is dizzying, nauseating, and near-constant: This is for you. If you want to challenge yourself with this kind of fear: This book is also for you. I know many who would find divine exorcism in a place of such extreme. And I don’t want to minimize or belittle this kind of experiential release.

Simply that I am not one who tends to experience it, in any context.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

And now we come to The Violin Conspiracy.

The book is an unrelenting crescendo. Starting deceptively quiet and moving to that delicious kind of crashing boom you want in a symphony. The 1812 Overture doesn’t launch immediately into the bit with the cannons. No, it opens modestly with a few strings. One of the great musical bait-and-switches, if ever there was one.

The Violin Conspiracy is the story of a Black violinist, Ray, who discovers that his old, worn, family fiddle is in fact a Stradivarius. If that doesn’t give you the feeling that you’re about to step into an old-school fairy tale—the Grimm brothers kind—then I don’t think I can help you.

But our tale opens well after all that history has been lived out. The book opens with this: a theft. A theft of that great violin. The family fiddle turned heirloom.

Here is the truth of a great mystery: You should be able to strap in for the ride. Like you’ve buckled yourself into your seat on a roller coaster. The clicks start and you know you’ve hit the point of no return.

But you should also be able to feel clever and solve the puzzle if you like. You should be able to be both readers at once: enjoying the thrills and working the jigsaw pieces. That is the delight of a great mystery.

Slocumb gives you all the clues to piece together the violin conspiracy in The Violin Conspiracy. And an experienced mystery reader might find the puzzle more obvious than they’d like. That, I believe, is the price of wrapping a coming-of-age story within the trappings of a double mystery.

And yet, The Violin Conspiracy takes you along for the ride, too. You’re swept up in the hunt: both for the violin and for its historical lineage. The violin has its own story and its own secrets. They are just as compelling as not knowing the whodunnit of it all.

But the piece that caught me the most off guard is the sense of distance we so often get in adult novels when moving into a past: the place where our protagonist is in his youth.

I reveal myself again, here. I largely write and read for young people. And so when I start the pages with such a close third, so in Ray’s mind, only to be pulled out with the perspective of an adult remembering—I can’t help but confess my disappointment.

Perhaps that makes me the ultimate winner in this showdown, getting to read and play with the intertextuality between these seemingly disparate works.

The Violin Conspiracy has such a sense of young Ray’s hopes and desires. It paints a picture of the kinds of adults who nurture artistic dreams, versus those who feel it is kinder—or perhaps just more satisfying—to crush such notions earlier rather than later.

And yet, we are not quite as emotionally with young Ray, the way we are with the older Ray. This is perhaps a convention of adult literature, versus that written for the young adult. But I couldn’t help but think that there could have been room for both here, as there was already room for a literary mystery, a thriller, and a bildungsroman throughout these pages.

I love a book that leaves me asking big questions. I love a book where I can see that the author stepped into the arena, willing to go down swinging. Perhaps that makes me the ultimate winner in this showdown, getting to read and play with the intertextuality between these seemingly disparate works.

What is an inheritance? What is a legacy?

What is it to take up space in the world?

What is it to go on fighting, even though you know the fight has been rigged against you, from the start?

For Manhunt, to take up space is to brawl. To fight with everything you have, as long as you draw breath.

But it’s the instability of inheritance presented in The Violin Conspiracy that I find myself returning to, as an idea and a question. The violin is both given and taken. Handed down and stolen. Lost to time and of proven provenance.

And so we return back to my whims. To my love of paradox and my delight in an instrument that can hold so many truths at once.

Advancing:

The Violin Conspiracy

Match Commentary

with Meave Gallagher and Alana Mohamed

Rosecrans Baldwin: Today’s commentary is going to be all Meave and Alana, but I want to jump in and quickly announce: Next Friday evening, we’re doing a live Zoom with our friends at Books Are Magic to discuss all things ToB! I’ll be moderating, joined by Alana and Meave, plus judges Calvin Kasulke and Christina Orlando. Sign up and see!

Now back to your regularly scheduled program. Meave?

Meave Gallagher: Ohhhhhhhhh, Alanaaaaaaaa, I’m crushed. I am not a Horror Person especially, and I had to stop reading Manhunt several times so as not to throw up, whether it was from the body horror or the emotional horror, or how sometimes anticipatory terror can make you nauseous. However, I also had to stop reading it several times because it made me cry so hard I couldn’t see. So, not seeing it advance bums me out.

Alana Mohamed: As someone who loves horror and crying, I did indeed struggle through some of the gruesome parts of Manhunt (perhaps a testament to the goriness of Felker-Martin's writing). But the novel also left so much on the page—everyone in that novel was hurt and hurting in really brutal ways—that it stayed with me long after I read it.

Meave: I know we’re both trying very hard to stick to sports here, but—there is more to this “body horror” story than its bodies, and it’d’ve been nice to know what our judge thought of the prose, or the pacing, or the plots.

Alana: Judge Safi mentions that the book is told from multiple perspectives, but she doesn’t really give us a sense of what Beth, Fran, or Robbie feel, or what motivates them. In a world where transphobic talking points about the “male body” abound, it seems like Manhunt aims to delegitimize them by (literally) picking bodies apart.

Meave: So, the other day, we touched on book bans that targeted material by/for/about minority groups, specifically those within the Venn diagram of racialized people and people with LGBTQ identities. Historically, when oppressed groups win recognition of even one human right, the majority reacts with further oppression: States established Jim Crow laws as the federal government abandoned Reconstruction; federal representatives intensified their arguments against women’s suffrage after Wyoming and Utah territories enfranchised women in 1871. Rebecca Dix directly connects the fight against Black liberation to the fight against women’s liberation.

Alana: To your point about the intersecting nature of these themes, I will say something that might be a little bold for me to say: I really bristle at this match-up. Black and trans people have historically been pitted against each other, as if their concerns aren’t two parts of a larger system. As if Black and trans stories are somehow not compatible.

Meave: Yeah. Brooklyn Liberation, to cite one, local example, refutes the idea that Black and trans stories are incompatible.

One could make a very similar argument about the perceived danger, or at least sense of not-belonging, of Ray’s Black body in the white spaces he enters, that “gender critical” people make about transwomen in “women’s spaces.” Our judge acknowledges these similarities before making her ruling, expressing pleasure at “getting to read and play with the intertextuality between these seemingly disparate works.” But before that, she describes The Violin Conspiracy as being “driven by heartache and longing. To love a thing that doesn’t always love you back. To refuse to give it up, regardless.” How dissimilar is that to Manhunt’s protagonists’ attachment to their identities, their senses of self? I find the thematic similarities between these novels much more interesting than their stylistic differences.

Alana: When I read Judge Safi on heartache and longing, I did indeed think about how much desire dictates in Manhunt. The horror comes from the words and actions of the cis women who populate the novel and the internalized self-hate Beth, Fran, and Robbie must navigate while trying to survive the external threats.

To that end, it feels like Manhunt got a bit pigeonholed as solely a work of horror. The Violin Conspiracy gets to be a literary mystery, a thriller, and a bildungsroman, but I could see the case for Manhunt as both a coming-of-age story and a thriller.

Meave: The Violin Conspiracy does appear to enjoy more explicit praise from the judge—which is a normal reaction to a book you really liked! And judges aren’t obliged to be even-handed. She explains that Manhunt’s “world where violence is dizzying, nauseating, and near constant” turned her off, then praises The Violin Conspiracy for being “an unrelenting crescendo.” The one big difference I see here is the manner of each book’s “experiential release.” You’ve got to have tension to have the release, no?

Alana: Toward the end of her review, Judge Safi really hones in on the violin. It seems like there’s something more appealing about the tension being to an object, rather than a human, which I think I can understand. It does seem like a mystery promises a different type of “experiential release” than an apocalyptic zombie novel, right? What’s interesting is that Judge Safi also talks about The Violin Conspiracy in terms of having a fairytale-like set-up, and says it falters when talking about Ray’s experiences as a young person, which seems like a pretty big failing for a coming-of-age tale. She says that the switch to a more reflective mode from “such a close third, so in Ray’s mind” pulled her out of the story and left her disappointed.

Meave: Now seems like as good a time as any to look in on the Library, which sits right at the intersection of radical freedom and oppression. Maybe starting with some joy before the misery parade? I’m heartened that the Colorado Civil Rights Division found in favor of a teen librarian who was fired for fighting back when her library canceled her BIPOC and LGBTQ teen programming. A state body ruling that “censorship targeted at LGBTQ youth or youth of color” is illegal discrimination, actually, is something.

Alana: It’s a relief to see book bans being blocked or challenged in court. Anytime I freak out about oncoming fascism, my parents, who grew up in Guyana under Forbes Burnham's dictatorship, are quick to point to the court system, which doesn’t necessarily fill me with much hope, but…I’ll take what I can get. Since we’ve last talked, I’ve found that Kelly Jensen at Book Riot has been on the censorship beat pretty doggedly. Highly recommend giving her a read for the bad, the good (there is good!), and the activating. She is constantly pointing out what many of us know: Book bans are not popular. We have the numbers to oppose book bans, we just need to be vocal against anti-trans talking points.

Meave: I’ll put in a word for Erin Reed as a good source for finding places to take local action. I know it’s the ne plus ultra of clichés, but “think globally, act locally” can be much more immediately effective.

Alana: Yes, and less paralyzing! (I repeat my call to use your local library frequently and get involved in other ways if you can!)

Meave: Well, after all that, how are you feeling about future commentaries?

Alana: Mostly, I hope we have some cheerier news about the state of libraries. But my curious brain is just eager for the next match-up—and to get to talk about it with you!

Meave: Yeah, this one has been a doozy. But I’m grateful to have had such a partner as you on this journey. Lucky for us, we’ll be meeting for the very next judgment, when Judge ML Kejera takes on economic and climate catastrophes, with My Volcano, the little indie that could, and 2022 National Book Award winner The Rabbit Hutch. Lighter fare for sure!

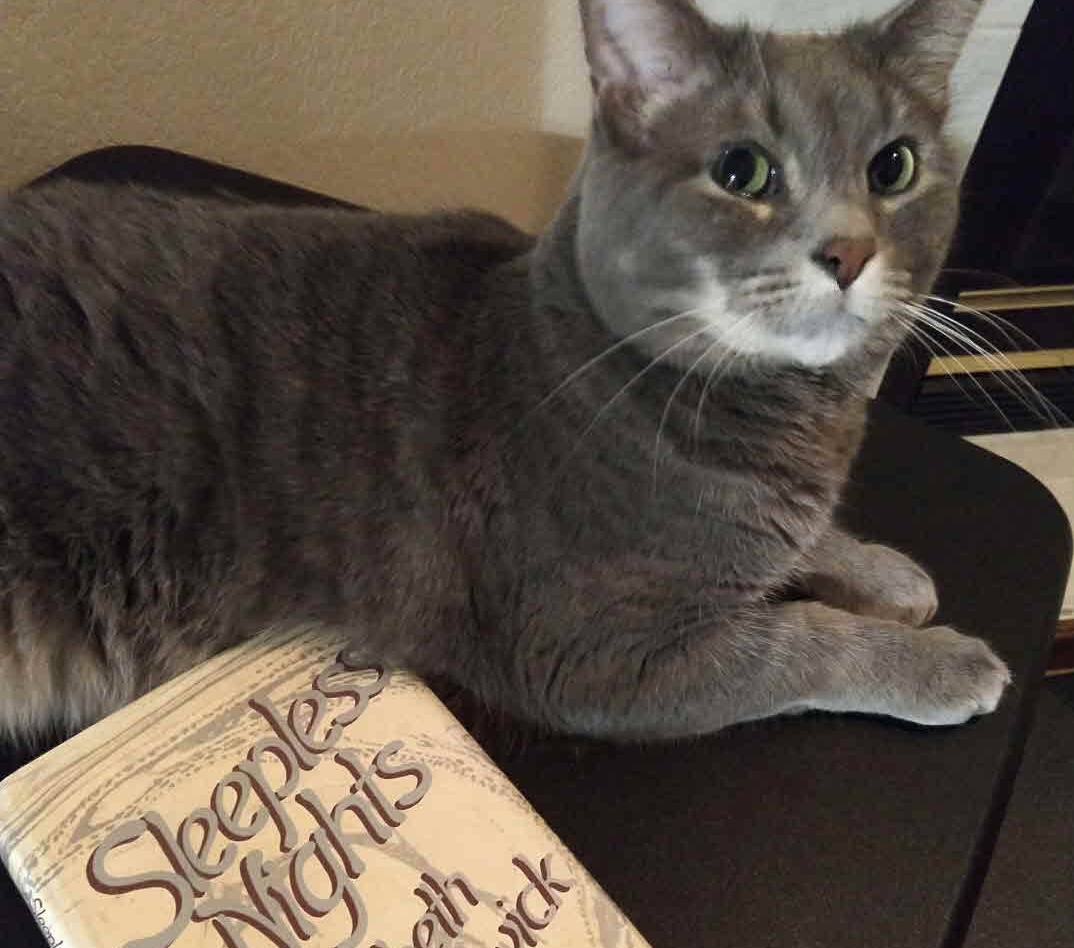

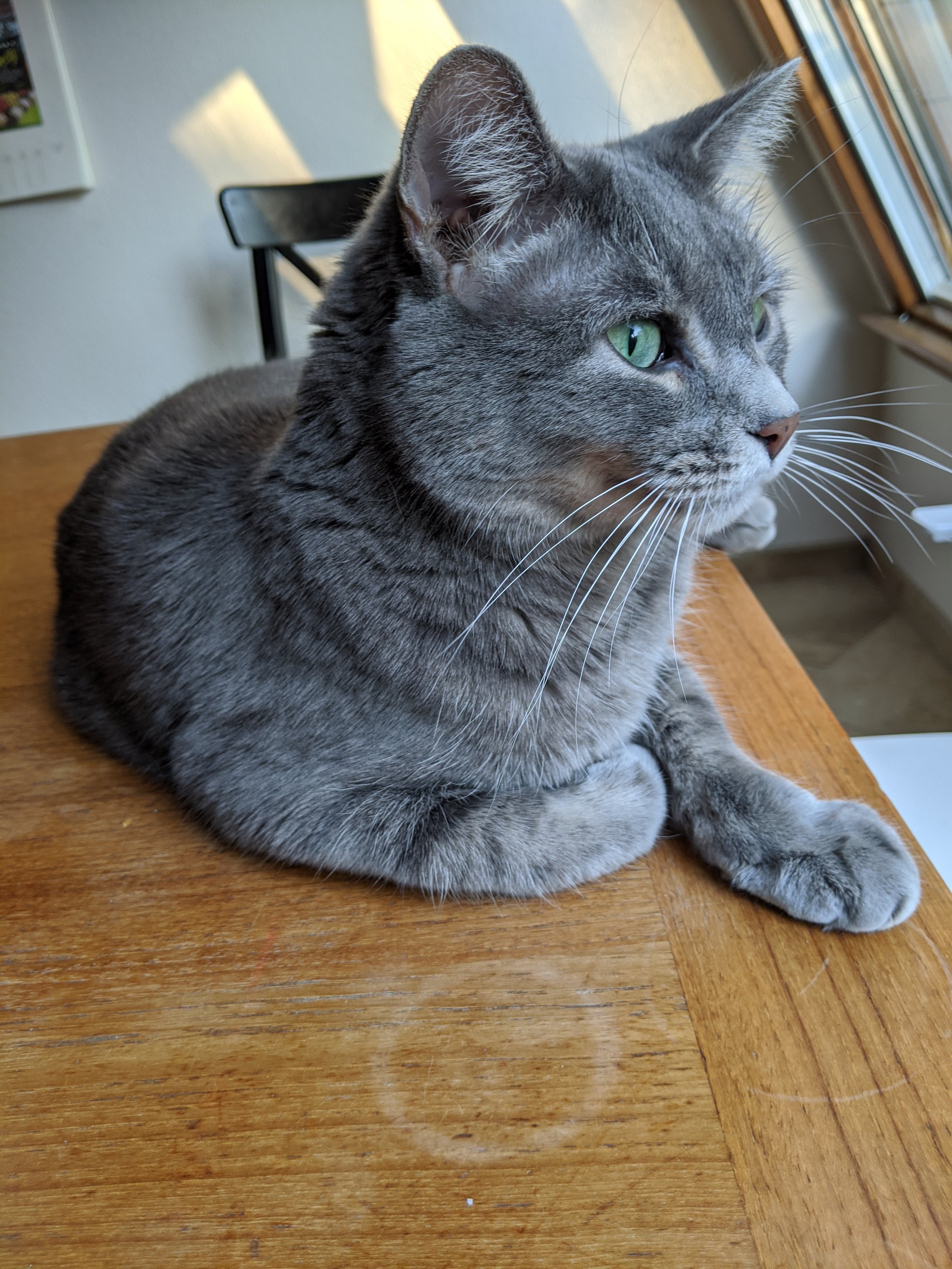

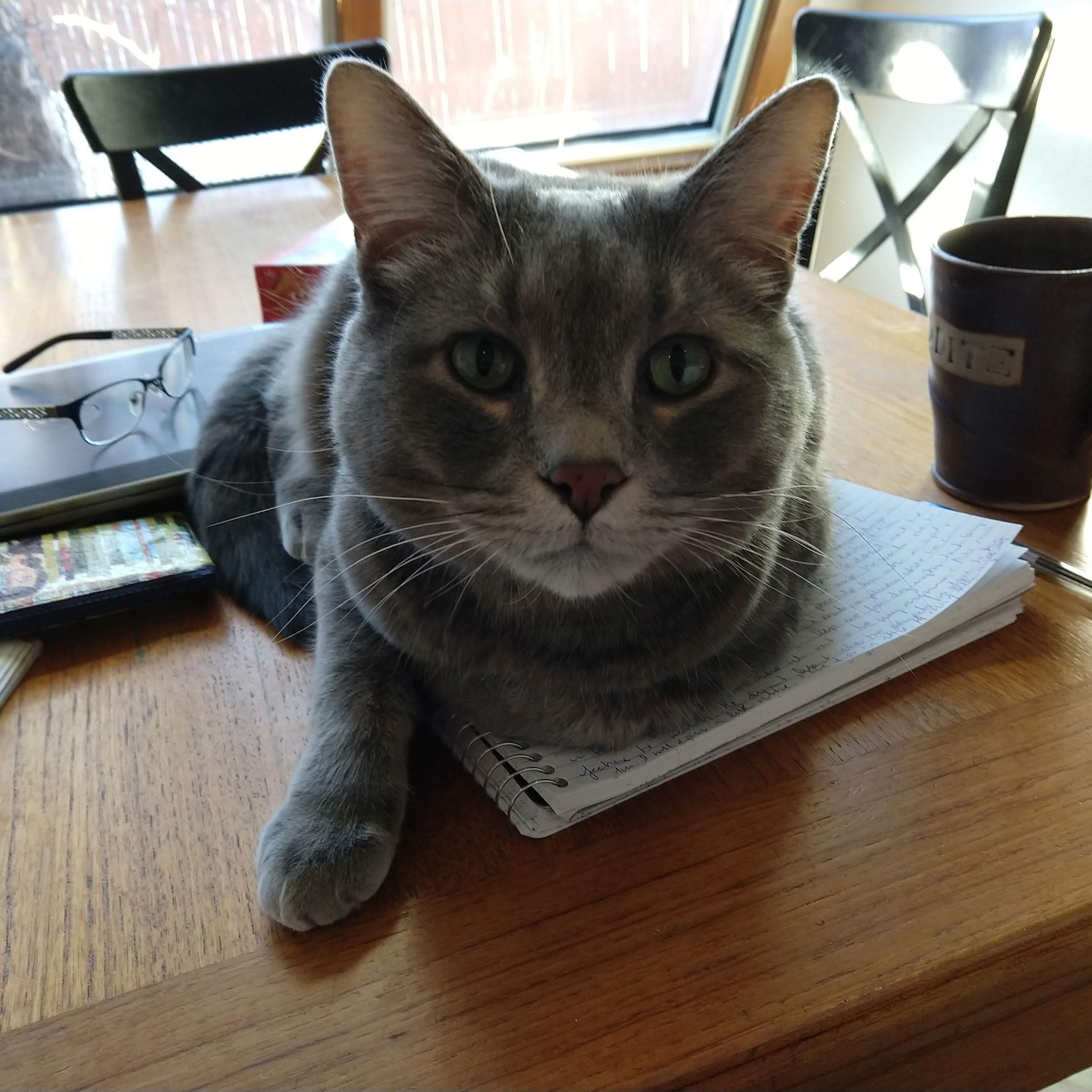

Today’s mascot

Today’s mascot is Obadiah, nicknamed Obie, courtesy of ToB fan Margot. Obie is a gruff old man of a cat, topnotch mouser, expert hider, and inveterate climber. He dislikes cold weather, loud noises, and most brands of cat food. He is currently engaged in a difficult relationship with a fox, which he would prefer not to discuss here. Obie enjoys sitting atop whatever book his favorite human is reading as she needs saving from the depressing, plotless novels about women she tends to read. Normally a very private cat, Obie agreed to this profile as the ToB has provided him with some excellent sit spots over the years. Welcome, Obie!

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.