Sea of Tranquility v. The Rabbit Hutch

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 28 • SEMIFINALS

Sea of Tranquility

v. The Rabbit Hutch

Judged by Torsa Ghosal

Torsa Ghosal (she/her) is the author of a book of literary criticism, Out of Mind (Ohio State University Press), and an experimental novella, Open Couplets (Yoda Press, India). Her fiction, essays, and other writing appear in Berkeley Fiction Review, the Massachusetts Review, Catapult, Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, Bustle, and elsewhere. She is an assistant professor of English at California State University, Sacramento, and a host of the Narrative for Social Justice podcast. Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / torsaghosal.com

Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility and Tess Gunty’s The Rabbit Hutch are novels of immense scope that stand at a decisive remove from narrowly conceived collages of modern life, the kind of contemporary novels Joyce Carol Oates calls “wan little husks” and Arundhati Roy labels “domesticated…[l]ike products.”

Sea of Tranquility opens with the deceptively simple account of Edwin, a gloomy Englishman, crossing the Atlantic to reach Canada in 1912. Edwin was forced to leave England sooner than expected by his parents, both “Raj babies,” after he made a few—rather meek, I must add—anti-colonial remarks at a dinner party. The opening is more historical drama than speculative fiction with Mandel shrewdly screening from view the narrative’s centuries-spanning timeline, the character ensemble and their array of perspectives.

The Rabbit Hutch, on the other hand, signals its interest in multitudinous lives from the start. The first sentence introduces us to Blandine Watkins, a girl who has aged out of the foster-care system, just as she “exits her body.” And while Blandine “exits her body,” a moment and image the narrative circles, she seems to be transfiguring into many people—“every tenant of her apartment building”—and many things—a pair of red glasses, an algorithm, a pair of tap shoes, and the list goes on. The splitting and proliferating of subjectivity are experiences she desires. For Blandine, individualism is the opposite of ethical life.

Faced with the task of choosing a favorite between the novels, I kept asking myself which of them works better as an artistic system.

Both Sea of Tranquility and The Rabbit Hutch made me think of those rare group photos that manage to exude something of the feverish energy of the party without freezing individual subjects into a tired pose. Their use of multiple points of view and variegated narration returned me to Mikhail Bakhtin’s conception of the novel as a literary genre that is always “in-the-making,” “in direct contact with developing reality,” a genre that includes a diversity of social speech types and voices to form a “structured artistic system.” To me, the idea of the novel as an artistic system implies a range of relations among characters, the time and space in which they are located, and the unfolding events. Faced with the task of choosing a favorite between the novels, I kept asking myself which of them works better as an artistic system. That is to say, I focused on how the several relations set up in a narrative world interact with one another and meaning emerges from them.

In Sea of Tranquility, we follow Edwin as he finds his way in the Canadian West. He is enchanted by the surrounding wilderness until he has a strange experience in a forest. His experience is vaguely outlined with sparse sensory details—“sudden blindness or an eclipse,” “notes of violin music,” feels like “being in some vast interior, something like a train station or a cathedral.” Before Edwin or I—the reader—can make meaning of the experience, the narrative hops a century and I am plunged to the middle of Mirella Kessler’s life where snatches of the eerie phenomenon in the forest returns, though there is no conspicuous trace of Edwin here. A bestselling pandemic novel in the 23rd century written by Olive Llewellyn, an author hailing from the second lunar colony, describes the same strange vision in the forest but its fullest implications are not evident to Olive.

Through these interconnected fragments, Sea of Tranquility tackles a plethora of ideas: the nature of time, technology, bureaucracy, crisis, colonialism. However, at the heart of it all is a moral dilemma having to do with the possibilities of human connection and agency. This dilemma is immanent in the narrative from the outset, but it became conspicuous to me only gradually, after I started to see how specific events involving distinct characters are related. I also admired that even as the narrative leaps over centuries, it lingers on moments of tenderness and longing, such as when Mirella realizes she misunderstood her friend Vincent but has run out of time to make amends.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

The Rabbit Hutch is set in a post-industrial wasteland, the fictional town of Vacca Vale, Ind., that was once home to Zorn Automobiles and has now fallen into economic ruin. In this dilapidated town, Blandine lives in a rundown apartment with three boys. The narrative dips us into not only Blandine’s consciousness but also those of her roommates, the other tenants of the apartment building as well as an erstwhile television star and her son. I have to admit here that I am a reader who is generally very fond of this sort of psychological narration. Few narrative elements engage me more than machinations and gymnastics of fictional minds.

All the characters in The Rabbit Hutch are sketched with quirky and, sometimes, amusing specificity, which I thoroughly savored: Blandine is obsessed with female mystics, a mother living in apartment C8 of the building has “a phobia of her baby’s eyes,” the television star takes a peculiar interest in pygmy sloths, and a Vacca Vale developer is “a jazzily dressed swamp monster willing to plunder his own home to eat.” Gunty also uses a range of narrative techniques: There are diagrams, obituaries, letters.

At the sentence level, Gunty is a stunning writer who names the ordinary and the extraordinary in the same breath. If life is sacred and worthy, then every life counts: Blandine’s life, the life of a fish, a goat, a cottontail rabbit, all of it. Looking at a dying fish, Jack—one of Blandine’s roommates—feels as though the creature “witnessed” him, it taught him something about his soul. But despite the novel’s interest in the sanctity of souls, the writing is most striking when it offers wry observations about living in an unjust society, loosely tethered to context. For example, while visiting a wealthy household, Blandine “finds the effects of bewitching real estate on her body deeply troubling” as she is unable to “reconcile it with her budding ideologies about private property.” The mother in C8 thinks “the plot of contemporary life” can be summarized as “everyone punishing each other for things they didn’t do.” Then there’s commentary about social media: “Everybody influencing, everybody under the influence, everybody staring at their own godforsaken profile, searching for proof that they’re lovable.”

The artistic organization of seemingly ordinary events produces dramatic effects.

The convergence of the various narrative arcs in The Rabbit Hutch is foreshadowed from the first chapter when Blandine is said to take on the essence of everyone and everything around her. The novel also repeatedly uses the opening episode—Blandine ‘exiting’ her body—as a signpost. However, when it all comes together it does not quite feel like a culmination—the artistic system does not seem to be striving toward meaning or purpose that is greater than the parts constituting it. The lure and strength of The Rabbit Hutch is voice—how it exploits the possibilities of language—not the complex interaction among events that make up the plot.

Sea of Tranquility is relatively more direct, even plain, in its use of language, but the artistic organization of seemingly ordinary events produces dramatic effects. The novel’s lure has to do with Mandel’s meticulous plotting. The fictional author figure, Olive, is criticized by her readers for not tying loose ends in her bestselling novel. Quite self-consciously, Mandel goes to another extreme. She exploits both chance and causality to tightly knit the various narrative strands. However, I found it refreshing that the chain of connected events does not extol an individual’s ability to change the world (overturning a popular assumption about plot and causality in the Global North)—the plot discloses how the world itself limits agency. A character who seemed to have been spared death because of another character’s intervention dies anyway within a few days.

Sea of Tranquility is unabashed in its commitment to a unity of action, thoroughly open to exposing its own intentional design. Reading the novel is a reminder that plot can theatrically elevate splintered experiences to conjure up a finer order of things, and that the semblance of order is captivating even if it must ultimately shatter.

Advancing:

Sea of Tranquility

Match Commentary

with Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner

John Warner: This is by no means a rare occasion when it comes to the judgments in our Tournament over the years, but I want to note that this is a great example of a commentary that really helped me see these books again, to see them better that I could have had I been left to my own experience of the novel. The notion of which kind of “system” at work in these respective novels works better is a fascinating way to consider these books in juxtaposition to each other.

Kevin Guilfoile: Sometimes the Rooster hands a judge a nearly impossible task. I’m not sure what criteria I would use to choose between these two novels. In fact, outside of the ToB, forcing yourself to make such a decision would be unnecessary, even stupid. Given the arbitrariness of the assignment, Judge Ghosal’s criteria is as good as any, and was an interesting read in itself.

Freed from having to make such a choice myself, my mind spent much of the time I shared with The Rabbit Hutch thinking about the short story. Several decades ago, a prolific writer could make a modest living (or at least supplement one) turning out short stories for magazines whose thirst for content was probably comparable to the Netflixes and Hulus of today. Virtually every literary genre we know was forged in eight-page chunks of cheap newsstand paper.

John: People familiar with my work know that I periodically invoke my great uncle, Allan Seager, who was a highly touted writer at the start of his career—called the next Hemingway by E.J. O’Brien, the original editor of Best American Short Stories, and the guy who discovered Hemingway—but through a series of bad breaks and a somewhat prickly personality wound up being largely forgotten not long after his death.

I have copies of a number of his papers and in them there’s notes like “Need to rebuild garage, story for Redbook, SEP [The Saturday Evening Post]...?” He would get paid thousands of dollars in 1940s-50s money for eight-page chunks, more than the average advance for a literary novel today.

Kevin: Fewer people read fiction than they did in Seager’s day, and even fewer read short stories on the regular. But a lot of people still write them. Writing short stories is probably the best way to learn how to create fiction in a school setting. You need a complete narrative that can be read in class, or taken home and critiqued by your peers and professors. Logistically, it’s the form that best suits the classroom. I have no data to back this up, but I’d guess that a sizable majority of the writers who still professionally publish short stories in the dwindling venues we have for the form are graduates of some sort of writing program. The short story has become an artifact of the fiction-educational complex. Indeed, a common and respectable path to publishing for The Next American MFA Idol has always been to sign a two-book deal and publish your grad school portfolio in a short story collection that almost nobody reads while you take the advance to go work on your much-hyped first novel.

John: I don’t have any data for this either, but I suspect you’re right. What’s happened to the short story happened to poetry before that—the form finding shelter in academe—but in finding that shelter, largely getting cut off from the larger reading audience, which is a shame.

Though I don’t know that there was an alternative path. Culture changes. Not only do we not see short stories published widely in the “slicks” of my great uncle’s day, publications that used to be vital outlets for short fiction (Esquire, the Atlantic, Playboy, etc.) don't publish fiction at all anymore. The New Yorker publishes many fewer short stories than in the past and the ones they do publish overwhelmingly come via the publishing industry, rather than “over the transom”—a term I saw someone recently have to define during a public talk because it was unfamiliar to the audience.

Where I would differ a bit is on the order of those books in the two-book deal. I think it’s now more likely for publishers to want a novel first, after which they may publish the stories, though I honestly think aside from some legacy writers (e.g., George Saunders) there’s very little commercial audience for short stories.

I know that in my Biblioracle work I often hesitate to recommend a book of short stories unless the requester has a book of short stories in their recent reads, so maybe I’m part of the problem.

Kevin: I am sure I read in an interview with Tess Gunty that The Rabbit Hutch began as a short story while she was in grad school. Sure enough, there are probably at least three chapters in this novel that are perfectly shaped and polished fucking diamonds. She could have lifted any of them from this novel with no other context and dropped them whole into the pages of the New Yorker and blown everyone away with them.

It seems to me the easy thing for Gunty would have been to package these and others as a short story collection, or even called them a “novel in stories” or something, which would have secured her a book deal but wouldn’t have been read by anyone save for adoring critics. Instead she developed intricate connective tissue and constructed a sophisticated novel that comments intelligently on a wide swath of philosophical and political subjects, from capitalism to feminism to religion, and on to social media and social justice.

Of course, you could be right. The modern business of publishing might have demanded a novel from Gunty. If so, there’s a National Book Award that says they were correct. Gunty is a spectacular writer who homered in her first at-bat. Anticipation for her next novel will be so high the entire industry is going to need to go on ACE inhibitors. But Mandel has had an impressive run from Station Eleven—which won the 2015 Rooster—to The Glass Hotel through Sea of Tranquility, three very different novels set in three different worlds, but which she has attempted to knit together in a fascinating metafictional multiverse.

Rosecrans Baldwin: True that! So, tomorrow begins the Zombie Round, and unfortunately The Rabbit Hutch did not receive enough votes to squeeze into the top two. Our previously vanquished titles who will be returning from the dead are Babel and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. See you, er, tomorrow, when Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow meets The Book of Goose and Thursday, when Babel faces Sea of Tranquility.

Today’s mascot

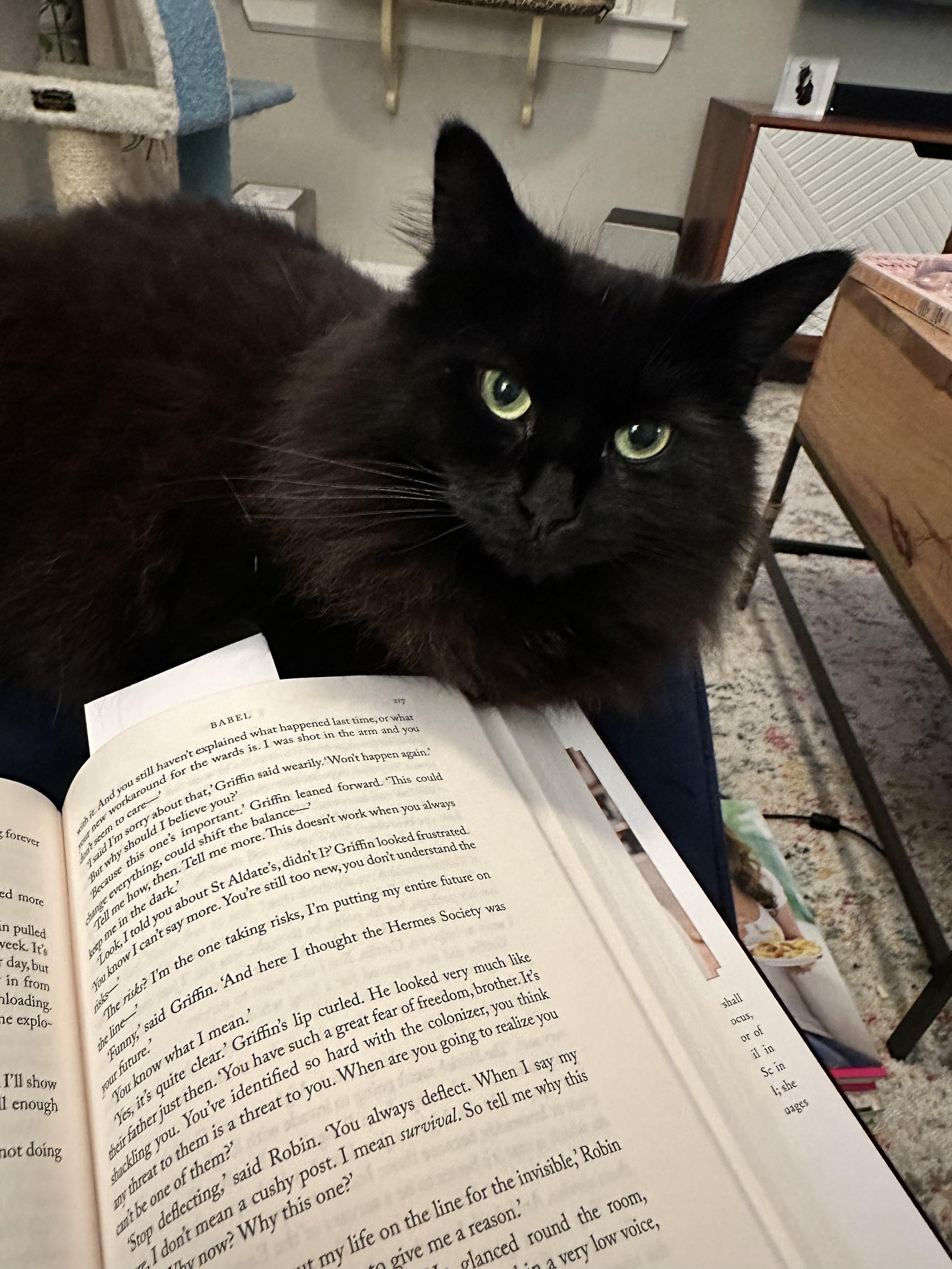

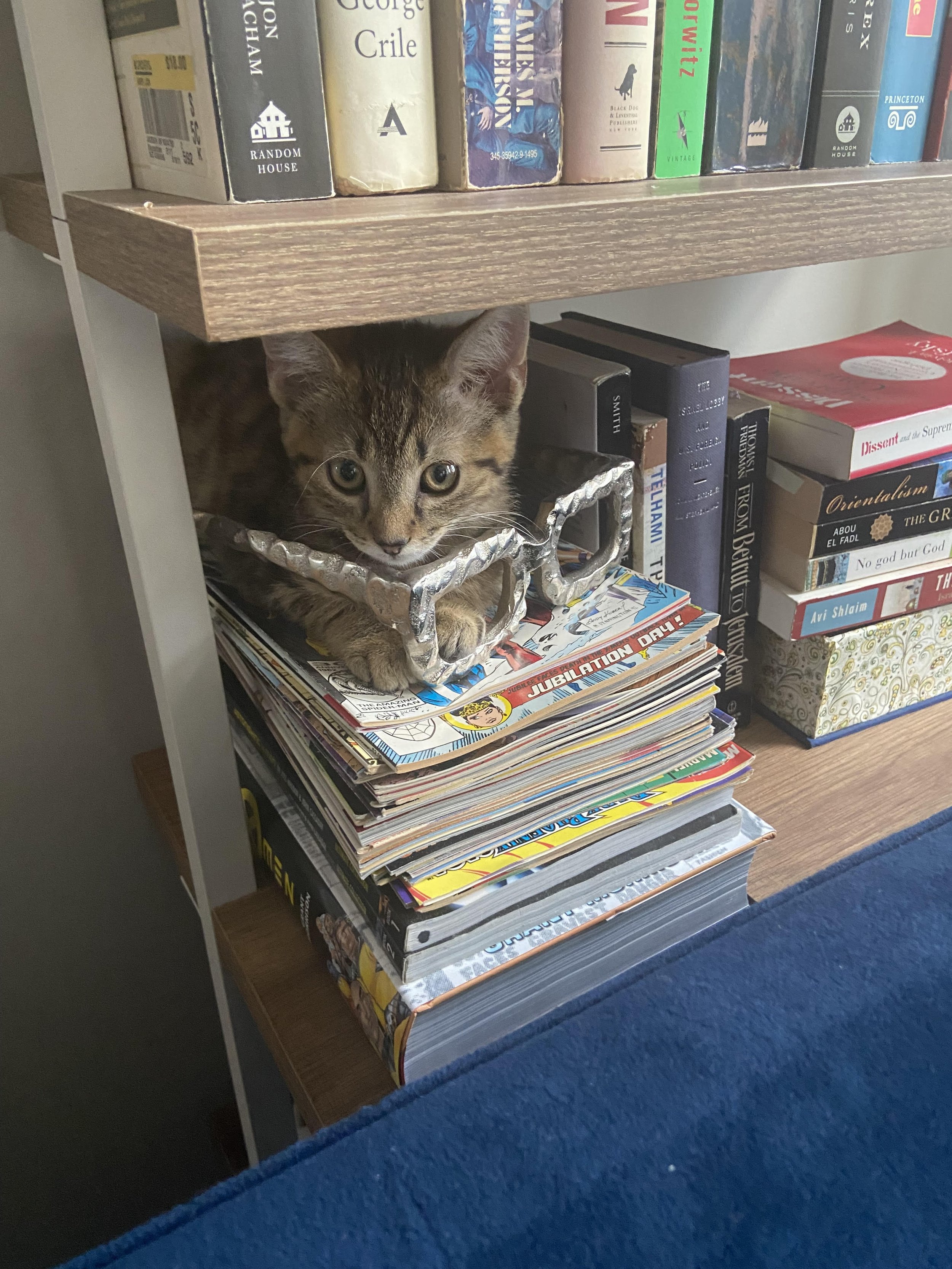

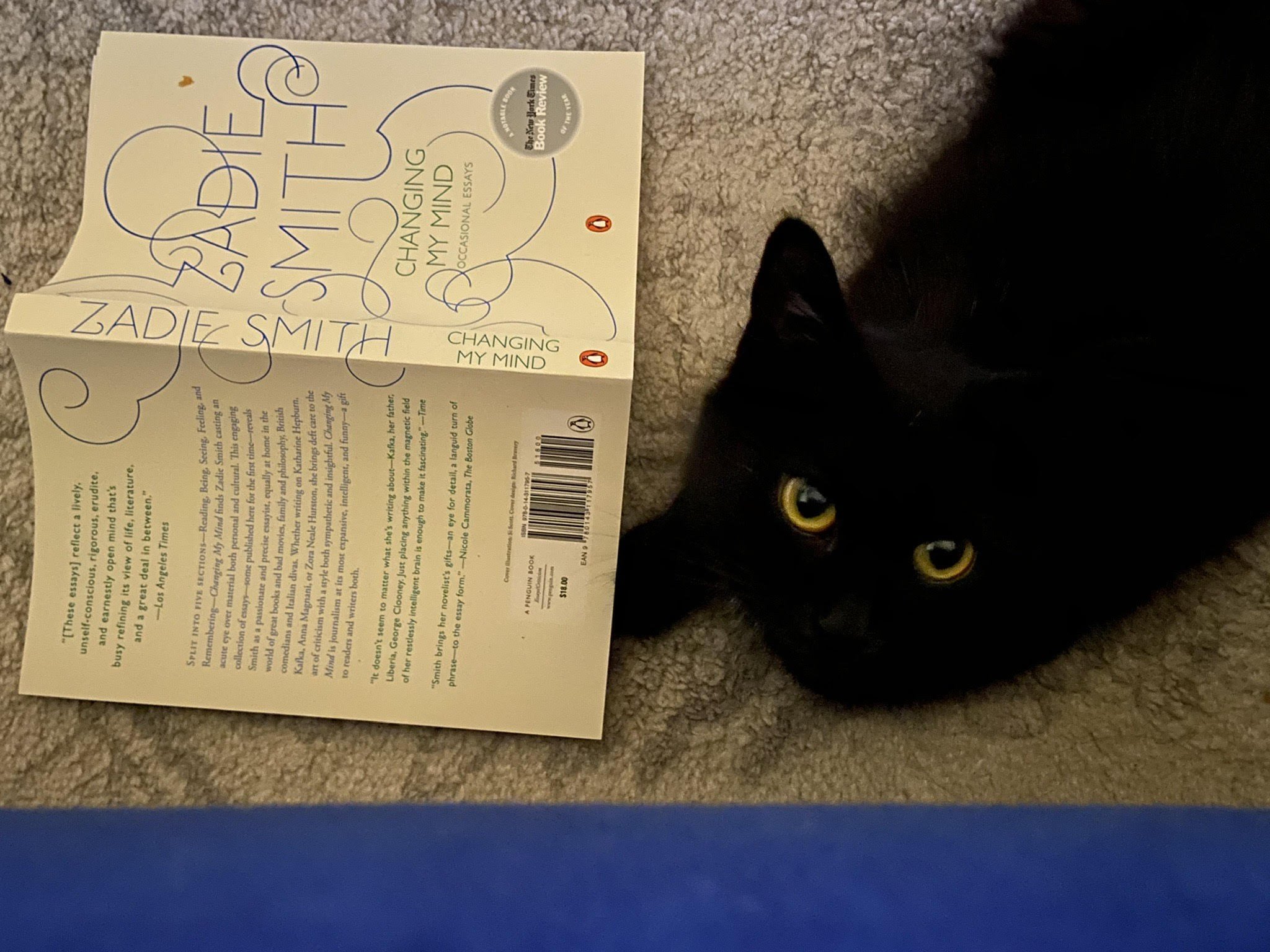

Say hello to Zadie, via Aneesa D.! According to Aneesa, Zadie is a black domestic longhair, named after author Zadie Smith. “Zadie is constantly being told what a beautiful girl she is and it has definitely gone to her head. While her younger brother, Gus Gus (short for Captain Augustus McCrae) zooms around the house, playing with anything that remotely resembles a toy, Zadie can usually be found regally posed on her chaise lounge or on her window seat, sitting in judgment of her other housemates. Other times, she can be found with her nose in a book. Or rather, with her whole body on a book.” Aneesa said that Zadie’s favorite book from this year’s ToB is Babel and she will most certainly judge the Tournament harshly if it doesn’t advance. We are warned!

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.