Blackouts v. The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

The 2024 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 25 • SEMIFINALS

Blackouts

v. The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

Judged by Elizabeth Minkel

Elizabeth Minkel (she/her) is a journalist and editor who’s written about books, fandom, and digital culture for WIRED, The New Yorker, The Guardian, the New Statesman, The Millions, and more. She’s the co-host of the long-running Fansplaining podcast and co-curator of The Rec Center, a weekly fan culture newsletter that was a finalist for the Hugo Award. She lives in Brooklyn with her cat, Orlando. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “Multiple mutual friends with Mattie Lubchansky, but we’ve had zero professional contact.” / elizabethminkel.com

I know it was partly down to the bracket seeding that Blackouts and The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store came to me at the same time—but it also felt like serendipity, because there were so many moments when these books truly seemed to speak to each other. Both are about the long American history of pathologizing and institutionalizing difference; both are about the way communities protect each other when those in power try to stamp them out. And both are about how communal histories are written and then lost, from Blackouts’ eponymous poetry and the queer lives it hints at, to the flood that begins (and ends) The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, literally washing the past away.

Of course, these themes are in the broader collective consciousness right now, just two of many examples, fictional or otherwise, of our attempts to excavate the deeply buried sins of the 20th century. But for all their similarities, the ways they diverge might be more interesting, especially on a formal level—because they approach those excavations from somewhat opposite directions. The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store’s sweeping maximalism, a world full of talkers, perpetually talking, stands in contrast with the sharply elliptical Blackouts, ostensibly a novel comprising almost wholly conversation, but which leaves so much more in its suggestions, and in its silences.

The sense of place is so strong that at times the omniscience felt almost physical.

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store is what I think of as a novel-novel: sprawling in every sense, with a narrator that hovers effortlessly over its huge cast of characters. The sense of place is so strong that at times the omniscience felt almost physical—or maybe metaphysical, like a ghost, slipping from one house to the next, shifting syntactically, moving with ease across time and space, and from the individual to the collective:

In the dawn’s early light, as the sun glimmered its first peek over the eastern slopes and shone down on the shacks and shanties of Chicken Hill, inside the very building where, in the warm basement twelve years before, love flew into his heart with the grace of a butterfly, and a beautiful young girl, now his wife, churned yellow into butter, pointing out the magic words of the Torah to him, a book she was forbidden to touch, her hand running across the page, revealing the promise held by words or sanctity, love, and history—the shutters of memory flickered again and he saw amid the crowd outside his theater the impish face, the hat, the tallit, the dimples of a young man standing among Jews of all types; then, as if a distant bell were ringing, like a train whistle in the distance, he heard, in distant memory, the wonderful wailing clarinet of Mickey Katz.

The ease of language in The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store makes much of the narration feel like a tapestry of well-worn stories, told again and again—anecdote, gossip, hearsay, legend, woven into a solid netting beneath their lives (somewhat ironically, of course, since much of the plot hinges on a boy who cannot hear). Despite the relatively happy ending, there’s a bittersweetness in the impermanence of all that chatter: a sense that the stories are changing as they’re passed from one mouth to the next, and that we’re seeing lives and cultures that will be lost to history when they finally fade away.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

Those same ideas of communal loss are threaded through Blackouts, though the massive cast of characters is winnowed down to two men, talking into the night. If The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store is a novel-novel, then Blackouts is something else entirely: an astoundingly unclassifiable book, cheekily toeing the line between fiction and nonfiction and daring you not to care. The cleverness of the erasures, the teasing winks of the photographs and other visual elements, and the sheer range of modes in those nighttime conversations almost defies description—I certainly couldn’t do it justice when I tried to explain to a friend what it was about while I was reading it.

Against other opponents, I would have chosen each of these books respectively—and maybe everyone says that at this stage in the game.

It is, at least in part, about constructing narratives to try and reclaim something—Juan and the narrator are ostensibly telling each other stories, but they’re also sketching portraits of their lives, pieced together from what they’re able to remember, and what they choose to remember. As Juan tells the narrator:

Who is it that likens nostalgia to returning to a familiar street only to find the geography has been tampered with? Half-real, half a rearrangement of the sleeping mind… Something like that. When I first read that line, it struck me as a warning—not to get lost back there, in the misremembered past, the half-dreamt barrio you can’t recall how to escape. Eh, niño?

For them both, the tampered mind is literal—the narrator with his blackouts, and Juan, slowly fading as the novel progresses. But there’s an inherently defiant queerness in the act of construction: the idea that you can always refashion yourself, and your history, to suit the person you want to be now. Blackouts is, of course, a deeply queer book, both in its text and in all its subtextual hints. Its dialogue is full of light, quick references, quotes half-remembered, hints of decades of queer cultural history that the narrator can already see won’t endure after Juan’s death, as much as he’s trying to absorb them.

Against other opponents, I would have chosen each of these books respectively—and maybe everyone says that at this stage in the game, but it’s true. They’re both exceptional, and I truly feel lucky I was tasked with reading them. I could choose based on format—Blackouts was arguably performing a higher-wire act with its riskier conceit, and I certainly thought it stuck the landing—or I could choose based on narrative, which would surely go to The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store and its whole town’s worth of moving chess pieces.

But I framed this comparison around style, so my judgment ultimately falls to style as well—and in the past, I have been accused of loving the elliptical a little too much. As powerful and poignant as I found The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, it was Blackouts, with its nods and its implications and its hinted-at-stories, with all that depth in its silences, that challenged me, amused me, and moved me. I couldn’t do it justice when I tried to describe it to my friend—but I told her that she absolutely needed to read it.

Advancing:

Blackouts

Match Commentary

with Meave Gallagher and Alana Mohamed

Meave Gallagher: Well, here we are again with our pals from earlier rounds. While I wouldn’t say that Judge Minkel has chosen style over substance, exactly, she does seem more moved by Blackouts’, as she puts it, “elliptical” style and less-standard structure. Makes me wonder whether, if she’d been judging earlier, we’d see The Lost Journals of Sacajewea instead of The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store here.

Alana Mohamed: Hello, Meave, and hello, old pals! I would have loved to hear Judge Minkel’s thoughts on The Lost Journals of Sacajewea, especially since she considers elements like format and style here. I wonder how much the two inform each other in Blackouts, given that erasure poetry is also elliptical and coy in the way our judge found amusing. Maybe that’s a bit in the weeds, though!

Meave: Alas, I have forgotten almost everything I ever learned about poetry. However, I wonder how many readers chose to engage with Blackouts as an audiobook. The publisher’s got one, but it seems like a wild choice for a sighted person to choose to listen to such a visual narrative. (Commentariat: No, we are not relitigating audiobooks in general.)

Alana: I’d be interested to hear what people using screen readers and audiobooks thought of this judgment! Judge Schnelbach’s decision in the opening round made me appreciate the visual qualities of Blackouts, but that element took a backseat this go-round. How do you feel about this judgment?

Meave: You know me, I like seeing a weirder book move ahead, even if I’m not sure I’d agree with the judge that the “hints of queer culture” that Juan relates “won’t endure” once he’s gone. Isn’t Blackouts testimony to the preservation of the parts of Juan’s life story he wanted to tell?

Alana: Totally! But those moments where Juan quotes a passage extensively and the narrator seems amazed—those elements will continue to filter down and warp, though Juan clearly thinks they’re important enough to recall on his deathbed. It ends up reinforcing the importance of “the act of construction” that Judge Minkel talks about. Complete recollection is impossible, so why not take the reins?

Meave: Put that way, the publisher’s comparison of Blackouts to Mañuel Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman seems pretty apt, specifically the footnotes: Per Tittler on Puig (1983), the act is “the work of an unidentified omniscient persona who is intent upon shattering the illusion created in the corpus of the text.”

Although Blackouts’ literal erasure of Gay’s bastardized and medicalized work, turning it back into something more like verse, are more complementary than in opposition to the “main” narratives. Still, I can see how our judge could get swept away by the form—and how it reflects the performance of rebuilding one’s own history.

Alana: Omg Meave, coming through with the citations! Kiss of the Spider Woman is an interesting comparison.

Meave: My dad loves the movie. I really should ask why.

Alana: I did often lose track of who was saying what in Blackouts, not quite parsing out…the truth? What’s real? It’s hard to articulate, since things become “real” in fiction as soon as they’re read.

Meave: I feel like we’ve been seeing more, as our judge put it, “toeing [of the] the line between fiction and nonfiction” in literature over the past…decade? Longer? Does it matter to you how much nonfiction is in a work classified as a novel? One needs primary documents to write a proper autobiography, right? So if you have a really good story with too many knowledge gaps, why not fill them in and call it a novel? That seems a little, I don’t know, self-indulgent?

Alana: Interesting! Do you think Blackouts’ use of primary documents saved it from feeling self-indulgent? Jan and the narrator are so referential when memorializing their stories. There’s a desire to uncover the emotional truth behind the primary documents, which strikes me as different from the project of “historical fiction,” as The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store might be categorized. But I wonder if that’s a fair distinction.

Meave: Well, as our judge puts it, “The ease of language in The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store makes much of the narration feel like a tapestry of well-worn stories”—and, to continue the simile, author McBride weaves it tight enough so you can’t see the warp or weft. Whereas in Blackouts, that work is deliberately shown; Judge Minkel says its power is textual and subtextual, which I think is right on. I still didn’t like it as much as other works in this year’s Tournament, but I am impressed with Torres’s accomplishment.

Alana: Both novels were ambitious and well executed! I don’t envy Judge Minkel for having to make a decision.

Meave: So, how’ve you found the decisions we’ve discussed so far? Any themes coming through? Judges Schnelbach and Minkel gave Blackouts the win in part because of its overt queerness, while Judge Deón advanced The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store because of McBride's skill within a more standard structure. Meanwhile, Judge Langbein advanced Monstrilio partly on the feeling that it ought to win—and it’s also quite dark and quite queer. Is this the gayest ToB yet, or is that selection bias?

Alana: I have been delighted to dive into this gay old ToB with you, Meave. It’s been fun to see our judges grapple with novels they found difficult. Judge Tan told us “frustration in a reading experience isn’t a bad thing” which hits the nail on the head for me. The judges we’ve seen have largely been able to engage deeply with their frustrations.

Meave: I wonder if this marks a return to the “weird little novel that could” days—though Blackouts did with the National Book Award, and the end of the Tournament isn’t quite nigh. Anything else before Kevin fills us in on which Zombie Blackouts will have to take down next round?

Alana: Just that I was tickled to see Judge Minkel describe the narrator as “hovering” over the cast of characters that inhabit The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store like a ghost. Judgments have also leaned spooky, as you’ve pointed out! The omniscience of the narrator could be termed god-like, but the image of the ghost is something sadder.

Meave: Well, Kevin, can you update us on the zombie poll?

Kevin Guilfoile: Pardon me for one second, but I am furiously counting and recounting the votes and can confirm that The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store has enough juice to bring it back for the Zombie Round! So, while it breaks my heart to say it, this means that we must say goodbye for good to Chain-Gang All-Stars. With just one more match to go before the Zombies, our brain-noshing novels are currently The Bee Sting and The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store.

Works citedTittler, J. “Order, chaos, and re-order: The novels of Manuel Puig.” Kentucky Romance Quarterly, 30(2), 187–201, 1983. https://doi.org/10.1080/03648664.1983.9930461

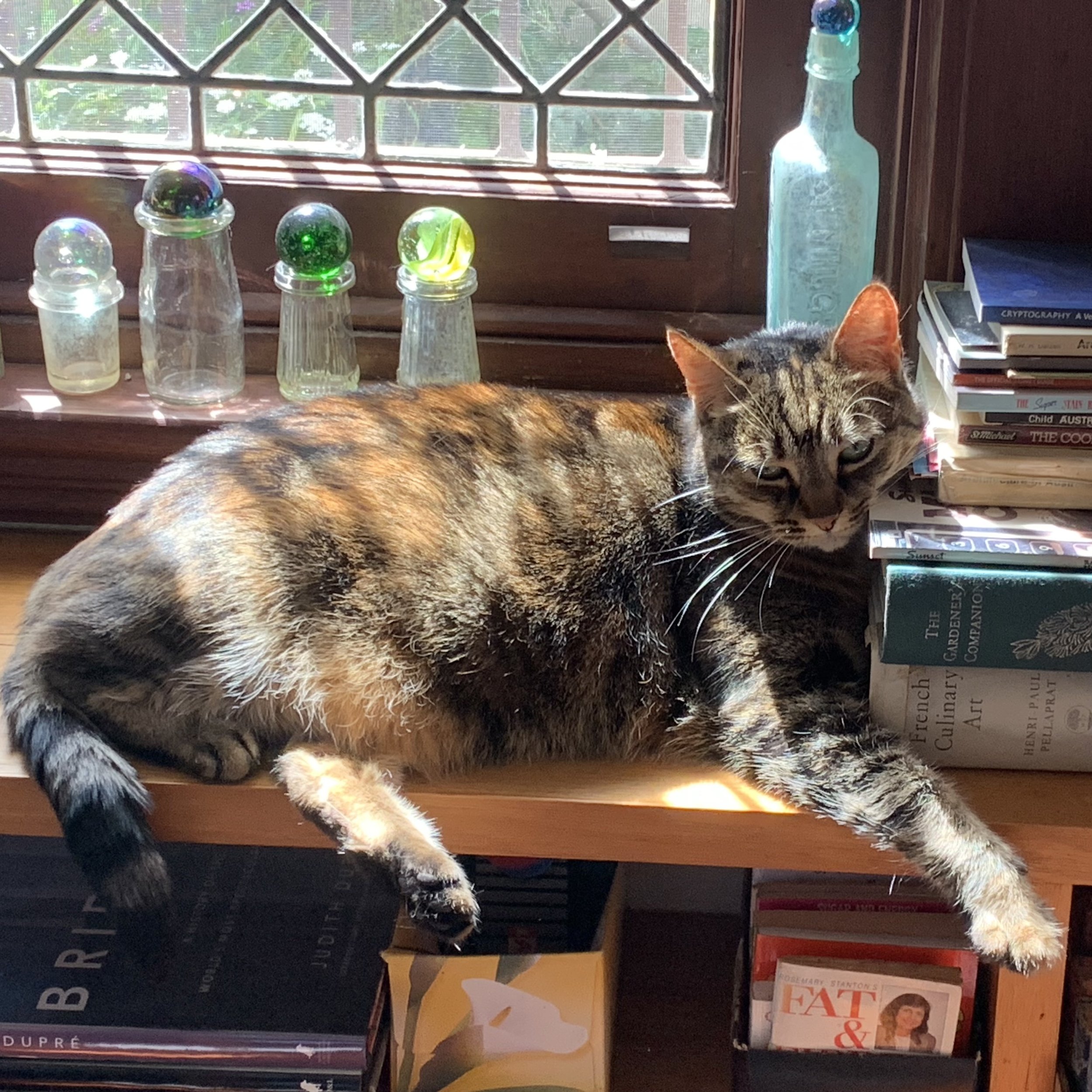

Today’s mascots

Nominated by Tania, Pippi and Sweet Pea are two mature chunky tabby ladies, enjoying nothing more than lying around in sunbeams, bossing the family around, and screaming for dinner.

Sweet Pea is a very judgmental reader, she would turn up her nose at anything popular, only reading award-winning novels. (She’s looking forward to reading the winner of the Tournament!) Pippi likes to lose herself in epic fantasy adventures, dreaming of being a fierce warrior. (In reality the Tournament rooster would scare her more than she’d scare him!)

According to Tania, “They were rescue kittens—we went to get one kitten from the vet but we couldn’t split the pair as Sweet Pea was such a nervous kitten without her big friendly sister, Pippi. Now, 13 years later, they prefer to ignore each other and hang out in separate rooms with their different books.”