Big Swiss v. The Lost Journals of Sacajewea

The 2024 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 12 • OPENING ROUND

Big Swiss

v. The Lost Journals of Sacajewea

Judged by Lucy Tan

Lucy Tan (she/her) is author of the novel What We Were Promised, which was long-listed for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize and named a Best Book of 2018 by The Washington Post. A recipient of fellowships from Kundiman and the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, Lucy is originally from New Jersey. She lives and writes in Seattle. Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / lucyrtan.com

You only need to read the first sentence of Big Swiss to know that Jen Beagin can write. “Greta called her Big Swiss because she was tall and from Switzerland, and often dressed from top to toe in white, the color of surrender.” Beagin has a knack for using detail and action to capture the essence of character. In the opening pages, Big Swiss is described as someone who has an aura “the size of a barge.” Fittingly, when she walks into the scene for the first time, she is introduced to us as a stranger who breaks up a dog fight.

The prose is full of turns and surprises, which charmed and captivated me so much that I sped through this novel. I don’t often find books funny, but I laughed when reading this one. The world is so over the top that it tips into the surreal. Set in Hudson, NY, where “the deeply deranged go to die,” we meet a gossip-fueled community of misfits, narcissists, and rich farmers. Its main character, Greta, is the child of not one suicidal parent, but two, and is sometimes suicidal herself. At 45, her personal trauma has translated into a mess of a living situation that finds her sharing a structurally unsound house with 60,000 honeybees and a drug dealer poor enough to steal produce but rich enough to buy and raise a pair of mini-donkeys. When Greta becomes infatuated by and begins a relationship with Big Swiss, whose therapy transcripts she’s being paid to secretly transcribe, Greta awakens to life and purpose, suddenly finding she has something to lose.

The humor in the book feels well matched to the darker material it addresses, not only in the sense that it eases the discomfort of reading it, but also in that it seems to say, yes, life really can be laughably horrible. Instances of suicide and assault are told with realism and subtlety, which grounds the interior lives of characters that might otherwise have seemed too exaggerated. I wished for a similar level of subtlety in the handling of the story structure, where plot and subplots build and release tension in a synchronized fashion, almost in direct response to Greta’s state of mind. When she’s keeping secrets from Big Swiss and avoiding dealing with her own trauma, her house is falling down, her roommate goes missing, and the honeybees are dying. Once her relationship with Big Swiss reaches its turning point and Greta finally goes to therapy, her roommate reveals where she’s been, the honeybee hive offers up 80 pounds of honey, and the mini-donkeys finally arrive, symbolizing new life. This neatness of structure seemed a disservice to the rawness of the characters themselves and the chaotic worldview of the rest of the novel. The memories that Greta finally shares in therapy are poignantly rendered, but I felt I was being led to a conclusion that I had already understood: All along, Greta was filling her life with disaster to mirror the disaster that she felt in her soul.

With books like this, the uphill climb is often worth it.

I was excited by the premise of The Lost Journals of Sacajewea: a fictional account of Sacajewea, as told from her point of view, with the goal of rewriting—or at least adding dimension to—the historical accounts found in the journals of Lewis and Clark. In it, we get Sacajewea’s journey as she searches for community and spiritual freedom despite a life held in captivity as a slave. Like Big Swiss, this book deals with dark matter, although rather than the gritty realism with which Beagin handles assault and rape, Earling’s depictions are poetic and sometimes metaphorical, although no less gruesome. The author uses what she calls “shattered prose,” full of imagery, line breaks, and punctuation (which serve as visual cues for rhythm and breath) to invent a unique voice for Sacajewea.

I struggled through the first half and most of the second. Dense with poetic turns of phrase and Shoshoni language, the book taught me how to read it as I went, and the learning curve was steep. With books like this, the uphill climb is often worth it. After a while the originality of the language pays off and becomes transportive, and this was true of The Lost Journals of Sacajewea even if the fictional ground I landed on often wasn’t firm enough for comfort. The locations and characters kept changing because Sacajewea continued to be on the move. I spent a long time trying to understand which characters were spirits and which were human, which experiences were shared by other characters and which felt real to Sacajewea alone. I struggled to fit this text into an idea of what I thought a novel should be, often growing frustrated by the lack of answers and feeling trapped in Sacajewea’s experience of events. And then, three quarters of the way through the book, I wondered if maybe that was the whole point—if the book wasn’t written for the comfort of the reader but rather with the goal of submersing the reader’s experience as deeply as possible within Sacajewea’s. If we feel disoriented and trapped, it must be because she is.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

Still, I missed the conventional thrill of novel reading, where the reader gets to understand more about the characters than they do themselves, and where I feel on solid ground rather than scrabbling through the shifting landscape of Sacajewea’s tale. In the first half of the book, there’s little character development of Sacajewea—it deals mostly with the trauma she witnesses and endures, and the elders that warn her about trouble coming. But isn’t character development a luxury of someone who has her basic needs met, as well as agency, not someone who is spending all her energy trying to survive? The book is about watching, waiting, and running because Sacajewea’s life was about watching, waiting, and running. It reads more like an artifact than like a novel, and in my opinion, it does what it sets out to do.

I should also say that embedded in the pages are memorable lines that relay hard truths with lovely precision. This passage resonated with me especially: “I tire of doors, Fort barricades, and white men’s stingy-gut ways to own all things and keep all things to their selves… Outside their doors and their barricades, we disappear.” Despite women’s lack of freedom in this novel, The Lost Journals of Sacajewea does a spectacular job of positioning them as the storytellers, and therefore the rule makers. Though my reading experience of Lost Journals was diametrically opposed to that of Big Swiss, both books are about how the stories we tell ourselves directly impact our survival.

I prefer flawed, ambitious novels over perfect unoriginal ones.

These novels delighted and frustrated me in their own ways. For me, frustration in a reading experience isn’t a bad thing; it means something about the book hasn’t aligned with my sense of what a story should be, and that I will spend time thinking about it after I’m through, often coming to know myself as a reader and writer better than I did before. Deciding between these books was the ultimate act of self-reflection, forcing me to define what I value most in a book. I prefer flawed, ambitious novels over perfect unoriginal ones, and both Big Swiss and The Lost Journals of Sacajewea fall into the former category. Both were stylistic and smart. One was fun to read, addictive, even, but left me feeling like it could have done more. The other was formally daring with a compelling concept, and ultimately hit its mark. But can I really vote for a book I might not have persisted in reading if I hadn’t been judging it for this contest? On the other hand, can I dismiss it on the grounds of not having given me enough of the conventional pleasures of novel-reading, when it is not a conventional novel? Can I fault it for being so, when it’s those very books that help expand the range of what we get to see in literature?

In Debra Magpie Earling’s words, “If there were only one story / Or one way of seeing all stories would die.”

Google shows me countless reviews of Big Swiss from big-name outlets while The Lost Journals of Sacajewea brings up only a few. I think it deserves more conversation, and it’s for that reason that I choose it to win this round.

Advancing:

The Lost Journals of Sacajewea

Match Commentary

with Meave Gallagher and Alana Mohamed

Alana Mohamed: As I read this judgment, I braced myself for a Big Swiss win, but I enjoyed seeing Judge Tan grapple with her own discomfort throughout The Lost Journals of Sacajewea. I thought it was an interesting line of speculation to say, “If we feel disoriented and trapped, it must be because [Sacajewea] is.” I’m not sure I agree with this reading entirely, but it seems like one way to experience powerful writing, albeit unpleasantly. Would you vote for a book that made you feel like a hostage?

Meave Gallagher: Funny you should ask. Lost Journals was one of my A-tier 2023 reads, while Big Swiss was, like, a low B. I’m sorry the judge felt hostage to Lost Journals, but I’m glad she used the experience to think more deeply about the book. Generally I’m much more open to unfamiliar plots than disorienting prose, as Judge Tan seemed to experience in Lost Journals. But ultimately I found Lost Journals almost freeing, in that I had to know how Earling was going to get Sacajewea through.

Alana: Right, a book can make you feel trapped and resigned to it, or it can encourage you to keep going. I’d be interested to hear more of your thoughts on Judge Tan’s assessment of Big Swiss, which I did not read this go ’round.

Meave: I thought this line, “The humor in [Big Swiss] feels well matched to the darker material it addresses,” was spot on, and I also felt the plot got a bit obvious by the end, when Greta starts to get her mind together and the rest of her life calms down, too. Also, with apologies for resurrecting this discourse, the way the judge describes Greta, as an almost deliberate disaster artist, made her a hard character for me to want to spend every second in her head.

Alana: Judge Tan talks about the growth of the protagonists in both novels. It doesn’t seem like either quite hit the mark for her. Greta “awakens to life and purpose” through her love of Big Swiss, but her growth “led to a conclusion that [Judge Tan] had already understood.”

Meave: Yeah, “Greta creates her own chaos”—easy to see that one coming.

Alana: In Lost Journals, the judge says, “There’s little character development of Sacajewea” in the first half of the book, and she misses the more traditional reading experience, “where the reader gets to understand more about the characters than they do themselves.” When it comes down to it, would you rather a story allow you to know better than your protagonist, or be kept at arm’s length?

Meave: One note: Switzerland is not known for its history of surrender but neutrality (if hoarding Nazi loot and exporting weapons counts as “neutral”). Was that deliberate on Beagin’s part? I can’t tell!

Alana: Ha! I did catch that. I assumed it said something about Greta that neutrality and surrender were so closely linked in her mind.

Meave: Funny, if true.

Alana: I’m not sure I agree that there was no character development in the first half of Lost Journals, which is all about her learning to observe the world as her parents see it, then survive without them!

Meave: Yeah, I thought that was kind of a huge part of her story. I’m not surprised a book without a traditional Western (English?) linear narrative offered a greater challenge. Most of us are more used to the voices of, like, beleaguered English-speaking muppets than novels that began as verse and—to my mind—fit better into a tradition of oral narratives and a different understanding of time. I may read more books like Big Swiss, but I’m more interested in stories like Lost Journals, and I enjoyed recalibrating my expectations to Earling’s style.

Alana: I think I also end up reading or hearing more about books like Big Swiss.

Meave: Simon & Schuster’s marketing budget must be exponentially larger than Milkweed Editions’.

Alana: Ha, fair point! At the end, Judge Tan factors the reviews Big Swiss has received into her judgment and advances Lost Journals since it “deserves more conversation.” Do you know how competitions like the ToB function in the wider publishing landscape?

Meave: I couldn’t speak to the ToB specifically, but I’d love to see even anecdotal data about it! I know we take competition winners into account when selecting books, or at least, we try to. There are just so many.

Alana: How much do you think media attention should count in a judgment? I appreciated Judge Tan pointing this out, but there was a part of me that wanted Lost Journals to win on literary merit alone—very lofty of me, I know!

Meave: No, I hear you. Finding a balance in the long- and shortlists—“celebrating big-name impressive books” versus “introducing worthy but more obscure works”—is something we always wrestle with. As part of the organizing committee, I admit I’m often the one saying, “This book that three people and I care about is so good, will you guys check it out? Maybe we can encourage thousands of people to read it!” Which is effective sometimes, but not always. Anyway, I think Lost Journals has more “literary merit” than Big Swiss, but if the judge chooses the book I like better because she thinks it deserves more critical attention, you won’t catch me complaining.

Alana: Very fair! I am ultimately happy it won and hope more people approach it with an open mind.

Meave: Same!

With that, we move next to Emma Cline’s latest troubled young woman, The Guest, versus Paz Pardo’s magical realism-cum-alternate history-cum detective novel, The Shamshine Blind, with Judge Isaac Fellman in the hot seat and John and Kevin commentating. I hope it’s as fun as I’m anticipating.

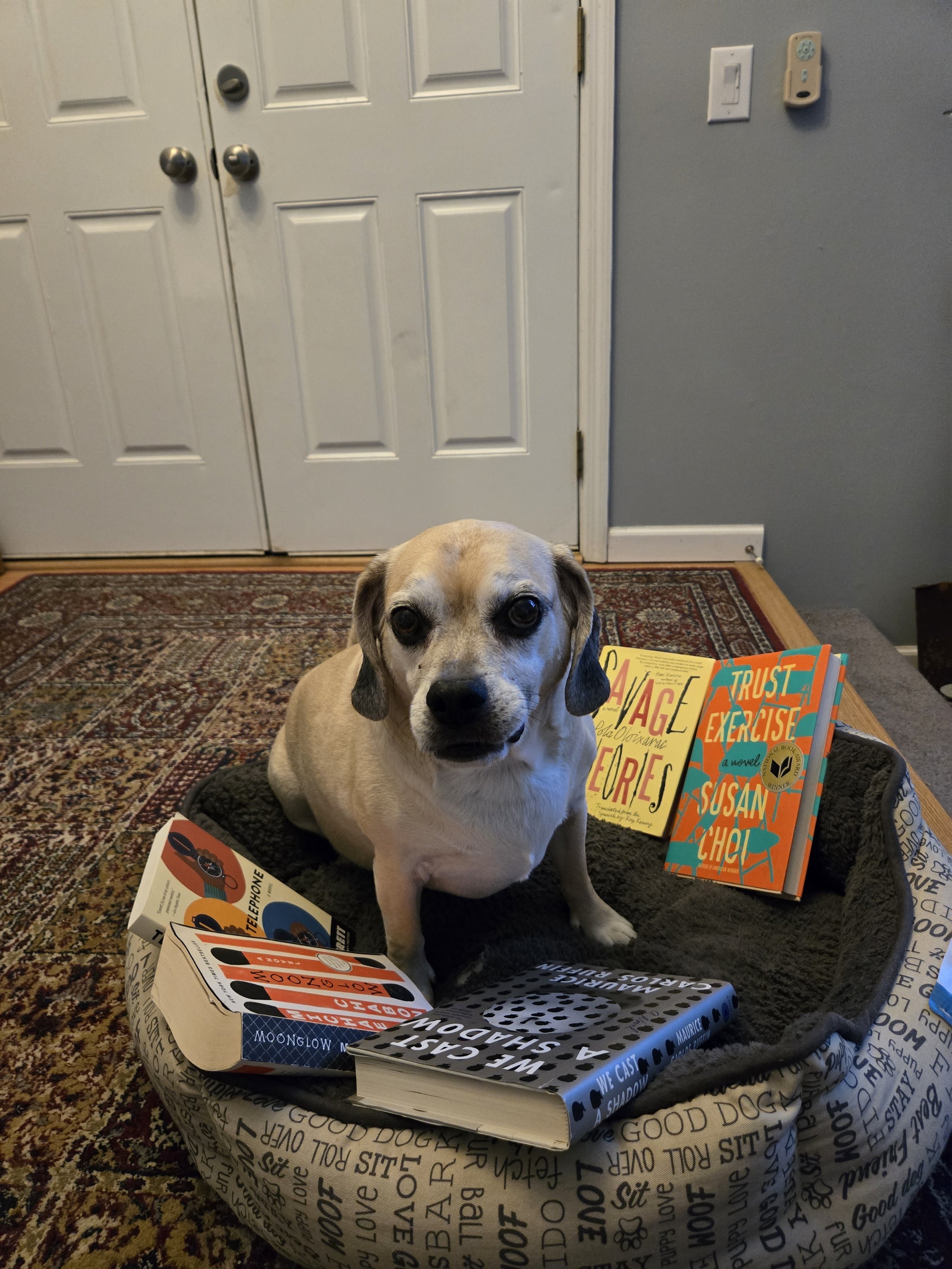

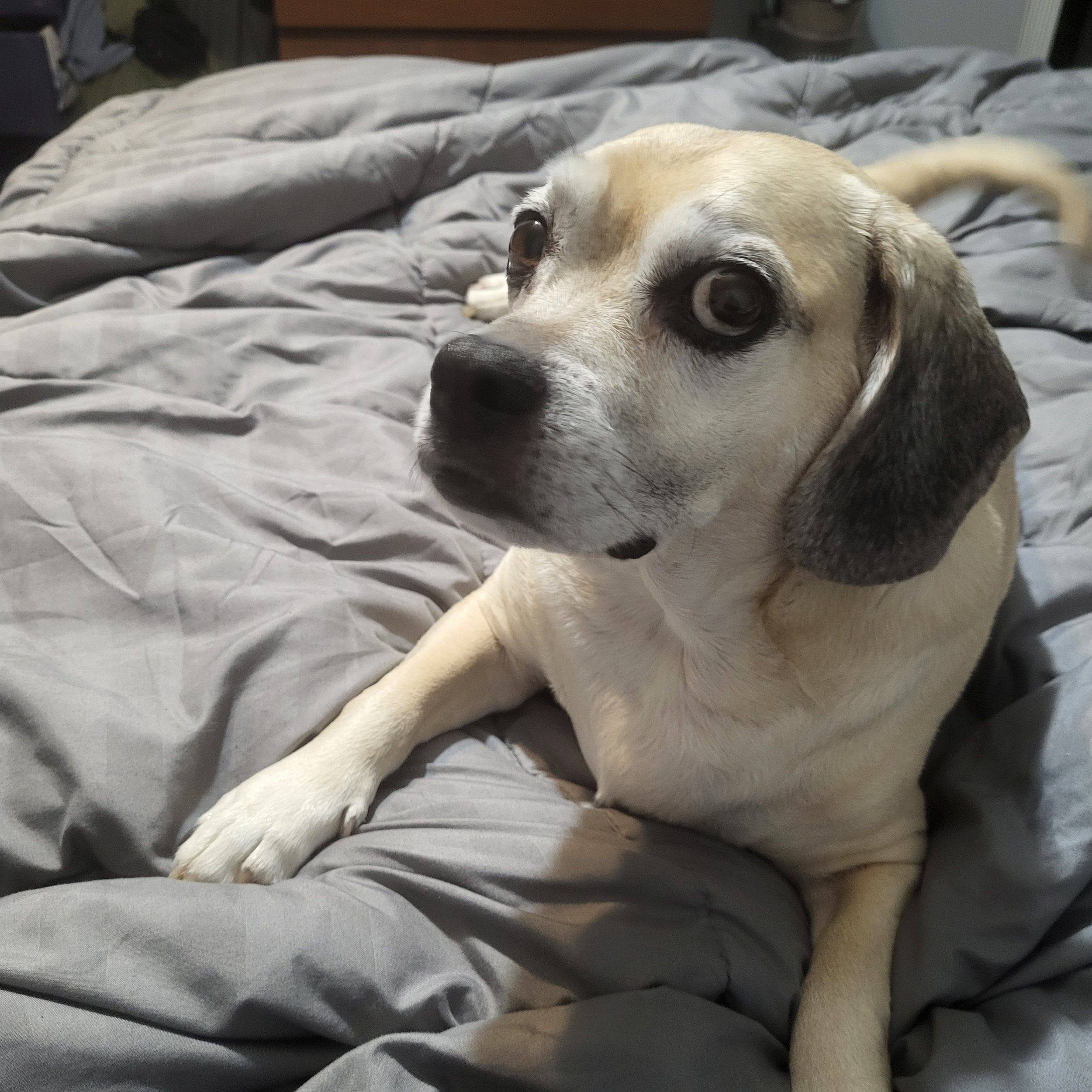

Today’s mascot

Welcome today’s ToB mascot, Goblin. He’s a puggle nominated by Heather, who tell us: “His favorite pastimes include sniffing, barking, going for long walks, smelling, eating everything his nose leads him to, and scents. Pictured here with some of his faves from Tournaments past, some of his all-time favorite novels include My Year of Meats by Rose Ozeki and The Scents of an Ending by Julian Barnes.” Thank you, Goblin and Heather!